On November 20, 1948, a mob of twenty armed white men shot and killed African American Robert Mallard in front of his family in Lyons, the seat of Toombs County. The killing initially garnered little attention, but due in part to the outspokenness of Mallard’s wife, the case soon became national news, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) entered the case.

Despite no evidence linking her to the crime, Amy Mallard was arrested by local officials for her husband’s murder. Eventually, two men—William Howell and Roderick Clifton—were indicted for the murder, but Howell was acquitted, and the charge against Clifton was dropped. After the acquittal, Amy Mallard toured the country on behalf of the NAACP, exposing the terror of mob violence in Georgia. The Mallard case revealed much about the practices of local and federal law-enforcement institutions, civil rights organizations, and the pre–civil rights era.

Political Climate

In 1948 thirty-seven-year-old Robert Mallard; his wife, Amy; and their two-year-old son, John, lived in a comfortable home on a farm in sparsely populated Lyons, on the banks of the Altamaha River. The Mallards, who were Black, inherited the property from Amy’s stepfather, a white landowner. Amy James Mallard, who had a college degree, taught at an elementary school in town and was well respected in the community. Robert Mallard was a successful traveling salesman from a ministerial family. His family and friends called him “Duck.”

In 1940s Georgia, racial animus was rampant and often manifested in violent outbursts. On July 25, 1946, the last mass lynching in the United States took place on the Moore’s Ford Bridge, at the border of Walton and Oconee counties. Two Black couples were beaten and shot multiple times. The crime was reported in national newspapers and led to mass rallies in New York City and in Washington, D.C., but no indictments were ever returned.

The 1948 Georgia governor’s race only increased racial tensions. The two candidates pitted against each other, Herman Talmadge and Melvin E. Thompson, knew each other well. A couple of years earlier, Thompson had been lieutenant governor under Governor Eugene Talmadge, Herman’s father. When Eugene Talmadge died on December 21, 1946, days before his inauguration in January, the state legislature selected Herman Talmadge as governor. Thompson challenged the legislature’s selection, and on March 19, 1947, the Supreme Court of Georgia held that the legislature had no jurisdiction to elect Herman Talmadge as governor. The unusual situation became known as the three governors controversy. (The third governor was Ellis Arnall, who was still governor when Eugene Talmadge died. Arnall refused to step down until a new governor was legally in place.)

In the wake of the supreme court’s decision, Talmadge and Thompson began to campaign for a special primary election scheduled for September 1948. Race played a central role in Talmadge’s campaign. He told his supporters, “When I am your governor, I assure you Georgia’s segregation laws will be preserved.” More than being segregationist, Herman Talmadge had concrete ties to the Ku Klux Klan. On November 18, 1946, he had been a featured guest at the birthday party for the Klan’s Imperial Wizard, Samuel Green. Throughout his 1947-48 campaign, Klansmen marched and burned crosses in dozens of Georgia towns to intimidate Blacks and discourage voting; they even placed miniature coffins on the doorsteps of Black leaders. Heading into the election, 82 percent of the white population over twenty-one years old was registered to vote, but only 18 percent of the Black population over twenty-one years old was registered.

On September 8, 1948, Herman Talmadge was elected as the Democratic Party’s nominee for the governor of Georgia. That same day Isaiah Nixon, a Black turpentine worker, was shot and killed on his porch in Montgomery County, which borders Toombs County, for voting in the election despite warnings not to. After Talmadge’s election, statewide NAACP membership plummeted from 11,000 to 3,000. Meanwhile, with the endorsement of the governor-elect, Green boosted state Klan membership to an estimated 100,000 members.

In Toombs County, where the Mallards resided, undercover observers for the Anti-Nazi League reported that the Klan had two or three discussions concerning the need for Klan activity. Cliff Vittur of the Ku Klux Klan reported that a demonstration was held in Vidalia, in Toombs County, on October 28, 1948. According to Vittur, 300 Klansmen arrived from all parts of Georgia and were met at the city limits by Toombs County sheriff R. E. Gray, the police chief, and the assistant chief, who escorted the parade into town. Vittur further stated that all three of the aforementioned officials, including Sheriff Gray, as well as all the officials from Vidalia except the mayor, were members of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Murder

On the night of November 20, 1948, Robert and Amy Mallard; their son, John; and two of Amy Mallard’s young cousins, Angelina Carter and William “Tim” Carter, were returning home from a gathering at the Oak Grove elementary school in Lyons, where Amy Mallard was a teacher. Robert Mallard, driving his shiny new Frazer automobile, turned onto a small path leading to their home, near the Providence Baptist Church (which had a white congregation). There they encountered several automobiles. A mob of men, standing outside the vehicles and wearing white robes, yelled “Hands up!” Amy Mallard recognized one of the men as her neighbor.

Suddenly, the mob opened fire at the Mallards’ car. Amy Mallard slumped to the floor of the car for protection. One bullet pierced the windshield and struck the chest of Robert Mallard, killing him. Once the mob dispersed, Amy Mallard got out of the car and saw her husband on the ground with blood streaming from his mouth. She ran to the home of a nearby farmer, Frank Brinson, who notified Sheriff Gray of the slaying. When Gray arrived at the scene, rather than attempt to locate the suspects, he searched Amy Mallard, emptied her pocketbook of all its contents, and read her personal letters.

Several theories emerged to explain the murder. One theory suggested political intimidation. Amy Mallard later testified during grand jury proceedings that her family had been warned not to vote in the November gubernatorial election that featured segregationist candidate Herman Talmadge. Another theory proposed that a recent incident outside Providence Church was motivation for the killing. Amy Mallard, driving the Frazer, honked the car horn in an attempt to have one of the white churchgoers move a car obstructing traffic—an unacceptable act in the minds of some locals. The most prominent theory, though, was that Mallard was killed because white neighbors resented his prosperity, embodied in his new car.

Officials’ Responses to the Killing

After the killing, Amy Mallard, her son, and her two cousins immediately fled to Savannah. News of the murder did not leave Lyons as quickly. Although the Toombs County sheriff’s office was immediately notified about the killing, it failed to investigate or comment publicly on the case for four days. Finally, on November 24, Sheriff Gray stated that witnesses told him that Mallard was killed by a group of white men wearing some “white stuff.” The next day Gray was completely dismissive of Mallard’s story, stating that earlier reports of the shooting were in error and that Robert Mallard was a “bad Negro.” Governor Talmadge ordered the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) to launch an investigation.

On November 27 Mallard’s funeral was held in Savannah. Amy Mallard’s brother, J. C. James, arrived at the funeral in the Mallards’ Frazer automobile, which had a single bullet hole visible in the windshield. At the conclusion of the funeral, agents from the GBI arrived, arrested Mallard, and charged her with her husband’s murder. The agents then drove her from Savannah to Lyons, where she was held for nine hours and finally released without bond. Her neighbor Frank Brinson and her two young cousins were also arrested. Before boarding a bus back to Savannah, Mallard became scared and hid out overnight in the woods.

Georgia officials failed to explain Amy Mallard’s arrest. On November 28, upon her release, GBI lieutenant W. E. McDuffie stated that he thought the Ku Klux Klan had been wrongfully accused in this case. Meanwhile, the Klan released a statement, signed by Sheriff Gray, exculpating the Klan from the Mallard killing. While little evidence suggests the murder was an official Klan killing, there were hints that the perpetrators and Sheriff Gray had ties to the organization.

The NAACP’s Response

Three forces spearheaded the NAACP’s involvement in the case: the national office, A. T. Walden, and Joseph Goldwasser. The national office, with special counsel Thurgood Marshall at the forefront, assumed immediate control of the Mallard case and insisted that the federal government intervene. The case, however, did not immediately lend itself to prosecution under federal statutes that required an obvious depravation of a federal right or clear state action.

All legal matters in the case were delegated from the national office to Black Georgia attorney A. T. Walden, who, perhaps strategically, limited his role in the case. Neither Walden nor the national office thoroughly investigated the killing.

Joseph Goldwasser, a Jewish businessman from Cleveland, Ohio, and a member of the Cleveland NAACP branch, decided to launch his own investigation into the Mallard killing. He arrived in Georgia on November 30, 1948, acting as an individual and representing no one. Disguising himself as a local farmer, he met with William Howell and Roderick Clifton, who both stated that they were part of the mob that killed Mallard. Goldwasser presented his findings to Governor Talmadge and threatened to turn over his information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation if Talmadge did not act.

Grand Jury

On December 3, 1948, after Goldwasser made his report to Governor Talmadge, the governor pledged that he would protect Amy Mallard if she returned to Toombs County to swear out warrants. The next day, five white men, Roderick Clifton, William Howell, James Spivey, Herschel Sikes, and Barney Sikes, surrendered and were held under suspicion in the case. After the men surrendered, a series of fires wiped out the Lyons Black business area. Few questioned that the fires were meant to intimidate Black members of the community.

Amid this tension, on December 8 Mallard returned to Lyons to swear out a warrant against William Howell. On December 10 a special grand jury session was held at the Toombs County Superior Court, which was crowded to capacity. After hearing an account of the slaying from Mallard, the grand jury indicted Howell and Clifton. Ralph McGill, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, also testified at the hearing regarding the “reluctance” of the Georgia authorities to bring the murderers to justice. The three other men who were held in connection with the murder were never charged.

Trial

On January 11, 1949, the trial of Howell was set to begin. Clifton had obtained a severance of trial. Mallard testified that her husband and their family turned off on a side road leading to their home and were stopped by a gang of “about twenty men, wearing white stuff and all carrying pistols.” She testified that she recognized Howell among the members of the mob, and also recognized Clifton’s automobile. During her testimony Mallard became hysterical and fell from the witness chair to the floor, kneeling with her hands in the air. She exclaimed, “It was so horrible! Why did they kill him? He was so good to us. . . . I’m so sick.”

Howell’s attorneys presented his defense through alibi, good-character testimony, and implied impeachment of Mallard. Howell testified that he spent the night with friends, and his friends corroborated this story. The defense sought to imply that Amy Mallard had a pistol that night. Defense lawyers further claimed that outside influences were trying to control the verdict.

Howell’s defense attorney, Thomas Ross Sharpe, employed a surprising legal maneuver during the trial when he called two jurors to serve as character witnesses in the case. The jurors testified that they would not believe, even under oath, the chief prosecution witness, Amy Mallard. The jurors also claimed that Amy Mallard had a “bad reputation.” The state prosecutor did not object to juror testimony, and the procedure was permissible at the time of Howell’s trial in 1949.

After only twenty-five minutes of deliberation, the jury acquitted Howell, and the courthouse crowd cheered in jubilation. The judge granted the county attorney’s motion to dismiss the indictment against Clifton, since the evidence against Clifton was weaker than that against Howell. After the trial, defense attorney Sharpe said of Goldwasser, “That roaring lion from Judea is a disgrace to the Jewish race. He wouldn’t even make catfish bait in the Altamaha River!”

Those who were following the proceedings, including the Black press, NAACP officials, and Goldwasser, concluded that the trial was a farce. Thurgood Marshall proclaimed that the arrest, indictment, and trial were perfunctory motions for the sole purpose of averting federal action. Mallard’s attorney, Aaron Kravitz, stated publicly that he was “satisfied” with the result of the “over-publicized” case.

NAACP Tour

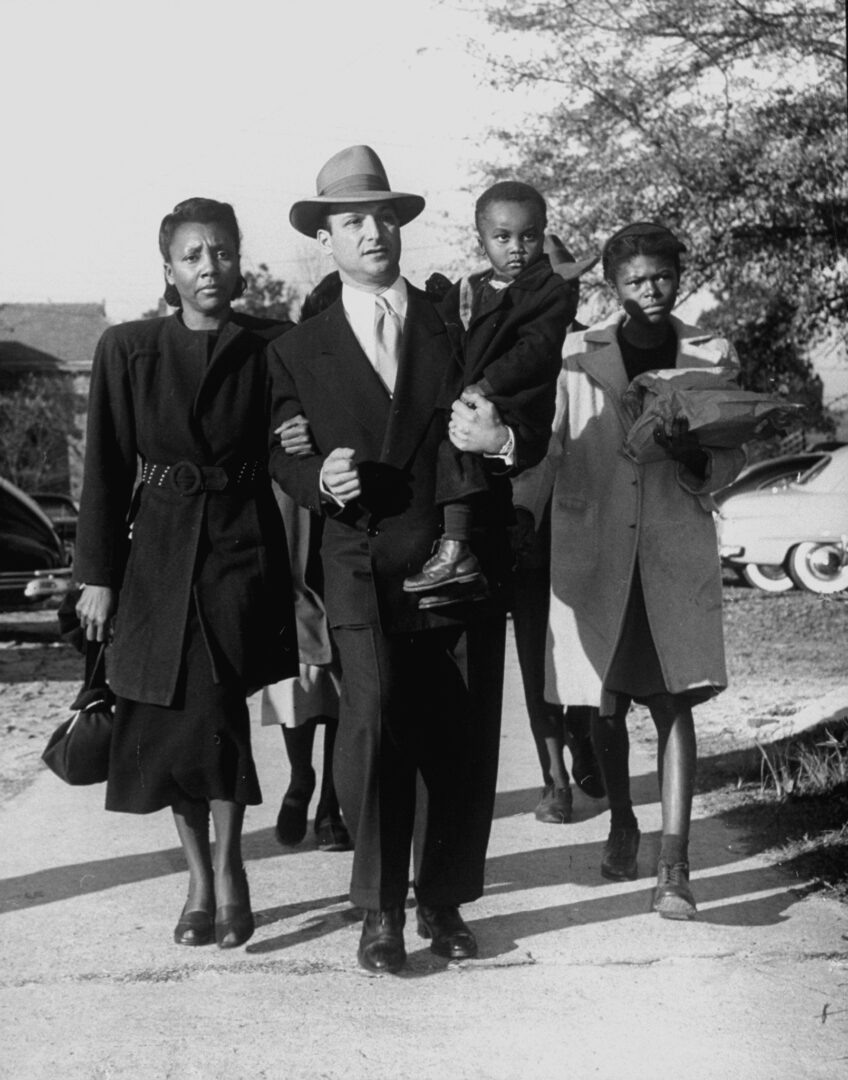

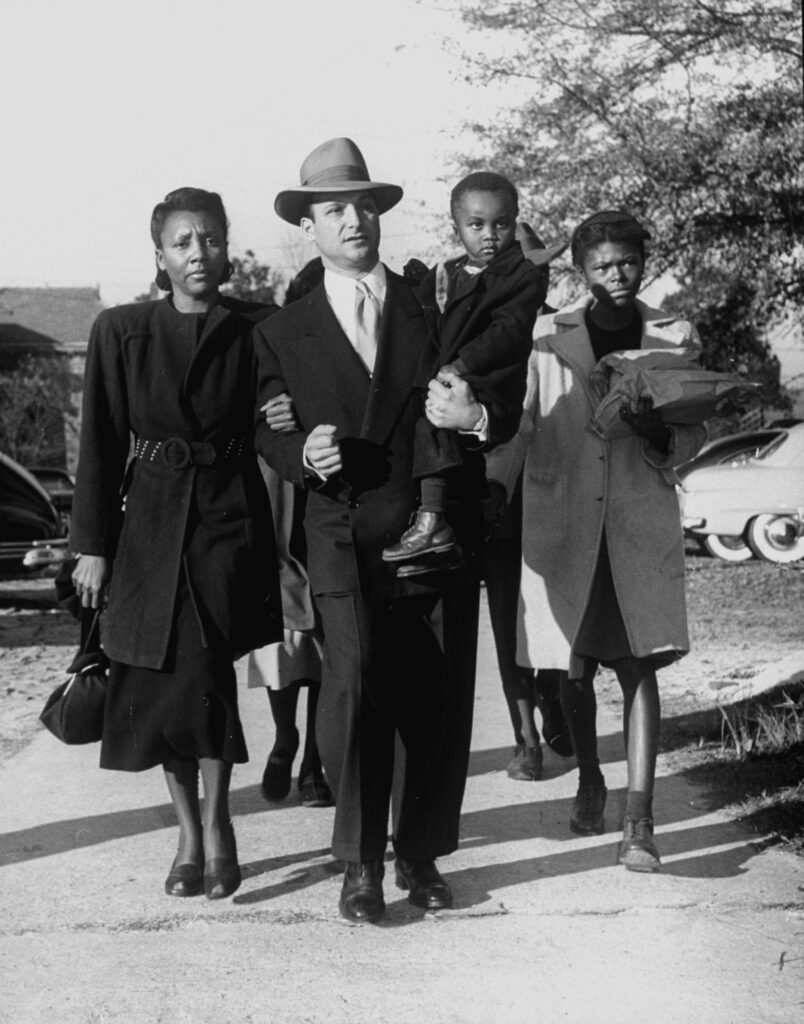

In 1949 the NAACP announced that Amy Mallard would make a tour under its auspices with her eighteen-year-old daughter, Doris Byron, and her two-year-old son, John, to promote the enactment of civil rights legislation, stimulate membership, and raise funds. Goldwasser traveled with Mallard during the tour in some of the larger cities. The tour began successfully. In Baltimore, Maryland, Mallard told the crowd of 2,800, “There’s no law in Georgia. Just dirty men. That trial wasn’t no trial. All-white jury; all-white lawyers; all-white everything.” She stated, “I’m going to spend the rest of my life fighting for democracy in America.” In Washington, D.C., 2,500 men and women jammed into a church to hear her speak. Goldwasser stated that, all told, the tour “enlightened many thousands of people.” After touring the East Coast, the NAACP cancelled the tour, citing a lack of funds.

On July 4, 1949, units of the Ku Klux Klan allegedly burned down the Mallard home in Lyons. Sheriff Gray was reported as saying, “It was just an accident. That woman hasn’t been back here to look after her property since she left.”

Indeed, Mallard and her son left Lyons for good, and relocated to Buffalo, New York. Little is known about the Mallards after this period.