In 1796 U.S. president George Washington appointed Benjamin Hawkins as “Principal Temporary Agent for Indian Affairs South of the Ohio River,” a position he held until his death in 1816. The city of Hawkinsville, the seat of Pulaski County, is named in his honor.

Although Hawkins was agent to all Indians in the South, he chose to live among the Creek Indians, who resided in present-day Georgia and Alabama. He built the Creek Agency Reserve on the Flint River in what is now Crawford County, where he lived with his wife, Lavina Downs; six daughters, Georgia, Muscogee, Cherokee, Carolina, Virginia, and Jeffersonia; one son, Madison; about seventy enslaved Africans; and a few Euro-American skilled laborers.

Early Political Career

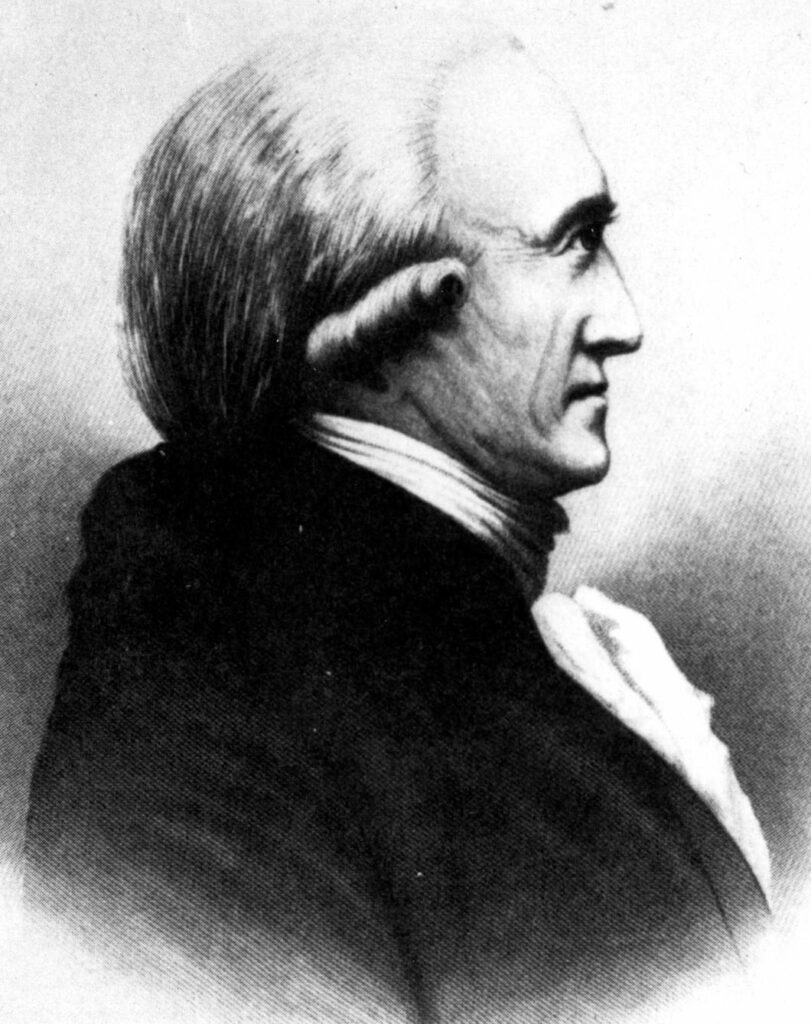

Hawkins was born on August 15, 1754, in present-day Warren County, North Carolina, to a wealthy family. As a young man, he attended the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), where he studied French. While he was there, the American Revolution (1775-83) broke out, and upon Washington’s request, Hawkins joined the general’s staff as translator. After the war, Hawkins began a successful career in politics, serving not only in the Continental Congress but also as North Carolina state legislator and, later, as U.S. senator. While serving in Congress, Hawkins took an interest in Indian affairs, and he was involved in several treaty negotiations with the Cherokees and Creeks. Through this work, Hawkins gained a reputation for being fair and just in his dealings with the Indians, which led Washington to appoint him as Indian agent.

U.S. Indian Agent

At the time of Hawkins’s appointment, the Creeks and other southern Indians were dealing with the economic stress of the failing deerskin trade as well as with the increasing pressures to cede their lands to cotton planters. To address these problems, the U.S. government devised the “plan for civilization,” a program to train Indian men and women in ranching (or livestock herding), farming, and such cottage industries as cloth making.

The underlying agenda, to acquire Indian lands, ignored the fact that the Creeks and other southern Indians had been farming since prehistoric times and that many had begun ranching when the deerskin trade started to falter. By transforming the Indians into yeoman farmers, so the thinking went, they would be assimilated as American citizens; they would then dissolve their national sovereignty and thus be willing to cede their territories to the U.S. government. Considering that the U.S. government was also considering more brutal methods for acquiring Indian lands, such as Indian removal and extermination, Hawkins understood the plan for civilization to be the best option for the Indians. He encouraged Creek men and women to experiment in growing such agricultural commodities as wheat and cotton and to increase the size of their herds of cattle and hogs, and he encouraged the women to learn cloth making.

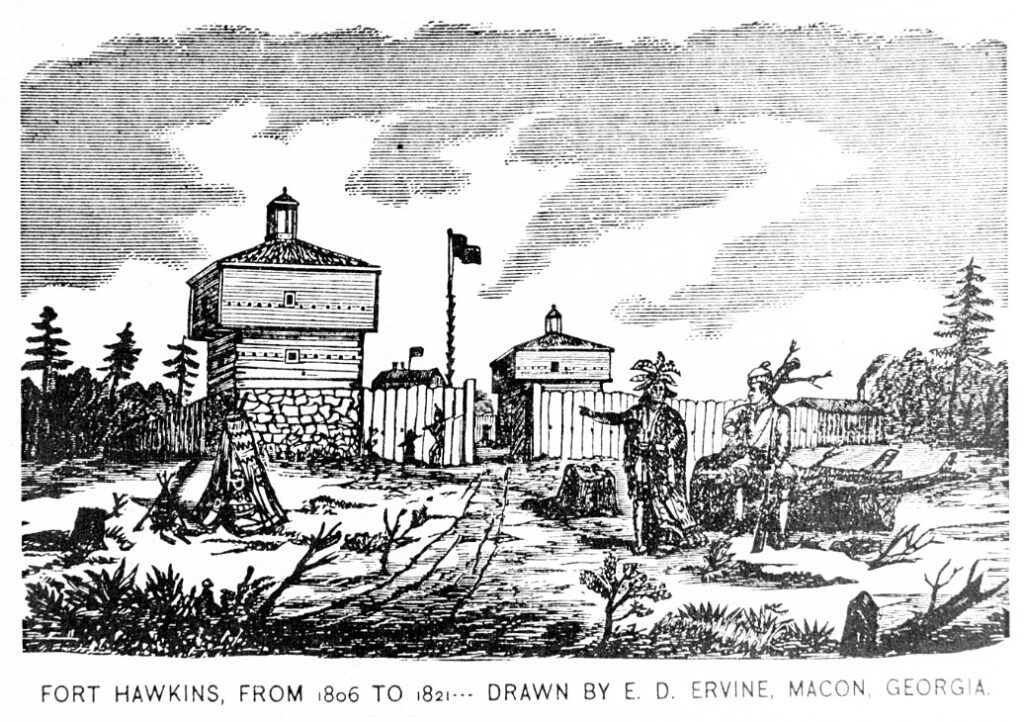

Courtesy of Middle Georgia Archives, Washington Memorial Library.

Because he was the highest-ranking federal officer in Indian country, Hawkins also often served as diplomat and general problem solver. There were the obvious diplomatic negotiations, such as treaty talks and trading arrangements. But Hawkins also intervened in more minor conflicts and disputes, and both Creeks and Americans often sought Hawkins’s counsel and his presence as mediator. In all cases, both large and small, Hawkins took painstaking care to collect and carefully assess the evidence. He also oversaw most military affairs, and Fort Hawkins, in what would later become Macon, was named after him.

Red Stick War

By 1813 the Creeks were transitioning from commercial hunters to commercial farmers, ranchers, entrepreneurs, and landholders. But, with increasing pressure to sell land to the United States, the Creek Confederacy soon divided over the issues of land sales, the plan for civilization, and whether to negotiate the never-ending American demands for land or to defy them. In 1813 these tensions erupted into a violent civil war. This was the Red Stick (or Creek) War of 1813–14, named after the rebels who became known as the Red Sticks. After a group of Red Sticks attacked Fort Mims in Alabama, the federal government got involved, and a combined force of Cherokees, Creeks, and Americans, led by Andrew Jackson, defeated the Red Sticks and razed most of the towns in Creek country.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Hawkins was disheartened, dispirited, and deeply depressed. He tendered his resignation on February 15, 1815, but in August, before he could resign, Jackson forced the Creek Confederacy to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which took lands from both allies and opponents, cutting away two-thirds of Creek country. Hawkins reported later that he was “struck forcibly” by the unfairness of the treaty, as were the Creeks. A year later, on June 6, 1816, Hawkins died in his home at the Creek Agency Reserve.