Berry Benson became a living legend thanks to his exploits during the Civil War (1861-65) and his postwar dedication to worthy causes. In addition, his image provided the model for the statue, meant to represent an anonymous soldier, that stands atop the lofty Confederate monument in downtown Augusta. Townspeople there came to refer to Benson as “the Man on the Monument.”

Courtesy of Edward J. Cashin

Berry Greenwood Benson was born on February 9, 1843, in Hamburg, South Carolina, the son of Nancy Harmon and Abraham M. Benson. In 1849 Abraham Benson tried his luck in the California gold rush, and the young Benson lived for some time with his grandparents near Greenville, South Carolina.

Civil War Exploits

When South Carolina seceded from the Union in December 1860, seventeen-year-old Benson was caught up in the martial spirit of the moment. He and his fifteen-year-old brother, Blackwood, joined the Hamburg Minutemen and were mustered in the First South Carolina Volunteer Regiment in Charleston. There Benson helped man the Edgefield Battery during the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861 and witnessed the federal fort’s surrender.

Benson accompanied his regiment to Virginia and enlisted for the duration of the Civil War after his six-month enlistment expired. Although just eighteen, Benson was named corporal of Company H, First South Carolina Regiment. Campaigning as part of General A. P. Hill’s Light Division in 1862, Benson saw action during the Seven Days Battles and at Second Manassas, both in Virginia; at Antietam, in Maryland; and at Fredericksburg, in Virginia.

In May 1863 at Chancellorsville, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee sent General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson with 26,000 men (including Hill’s division) on a long march around Union general Joseph Hooker’s position and caught the Union army in the flank. Benson marched with Jackson’s men and helped roll up the Union line until darkness fell. Later that night he heard the volley from fellow Confederates that would end Jackson’s life. The next morning, during the attacks that completed the Confederate victory, a minie ball smashed into one of Benson’s legs, crippling him. He returned to Augusta to recuperate and therefore missed the Battle of Gettysburg that July. In Augusta he met Jeannie Oliver, who would later become his wife.

Benson rejoined Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and completed his recovery in winter camp near Fredericksburg. The spring of 1864 brought another Union offensive into the Wilderness. After a confusing, bloody battle in dense woods, the Union commander, General Ulysses S. Grant, attempted to get around the Confederate army and march on Richmond, Virginia, but was checked at Spotsylvania, Virginia. There followed one of the most terrible battles of the Civil War, in which the severest action occurred at the “Bloody Angle,” where Benson fought.

By then the young soldier had won a reputation for scouting enemy positions. At Spotsylvania he reconnoitered the Union camp and on an impulse stole a colonel’s horse, leading it back to Confederate lines. Sent out a second time on Lee’s orders, he was captured and interned at the military prison in Point Lookout, Maryland. On the second day of his captivity, Benson slipped unseen into the waters of Chesapeake Bay and swam two miles to escape. Recaptured in Union-occupied Virginia, he was sent first to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., then to the new prison camp at Elmira, New York. Berry entered into a plan with some other prisoners to dig their way out. With incredible difficulty they completed a sixty-five-foot-long tunnel and made good their escape. Benson used one ruse after another during his lone journey through enemy territory before rejoining his regiment.

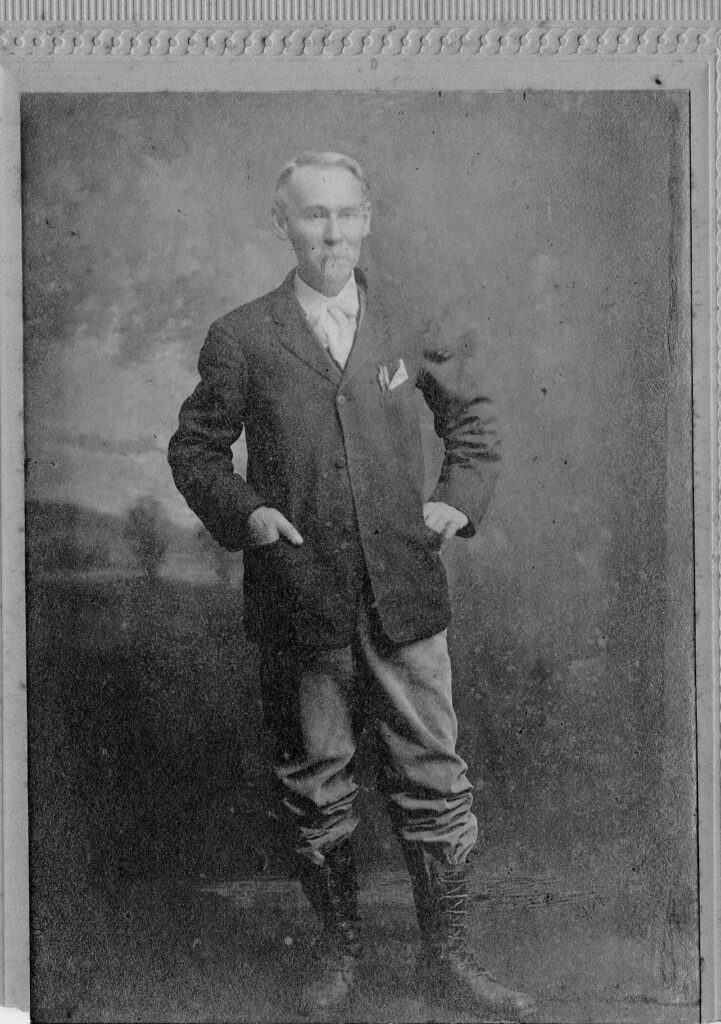

Courtesy of Edward J. Cashin

Finally furloughed in the fall of 1864, he returned to Augusta to find that Union general William T. Sherman’s troops had bypassed that place to besiege Savannah, and he immediately joined in the city’s defense. Only after the fall of Savannah did he return to his unit in Virginia.

In early 1865 Benson served in the lines outside Petersburg, Virginia, as sergeant of an elite regiment of “sharpshooters.” Later he commanded an independent unit in the retreat from Petersburg to Appomattox, Virginia. He and his brother, Blackwood, decided not to surrender with Lee’s forces at Appomattox but to join General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate army in North Carolina. But once there they found Johnston on the verge of surrender, so they traveled on to Augusta with their rifles, never having surrendered.

“The Man on the Monument”

Although no welcoming celebrations greeted the returning veterans, sentiment for the “

Photograph by Melinda Smith Mullikin, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Life after the War

Benson married Jeannie Oliver in 1868, and they had six children. After working several years as a cotton broker, and after a brief stint in Texas, Benson settled in Augusta as an accountant. He invented a failsafe method for checking and correcting even the most complex accounts and sold this “Zero System” nationally. He and his wife wrote poetry for publication, and his wife and daughters were all fine pianists. One daughter studied violin in New York and became a concert performer.

Although Benson audited books for the local mills, he was sympathetic to the plight of the workers. During the textile strike of 1898, he was the most prominent private citizen to champion the cause of the workers, and he served as an arbitrator in ending the strike. He experimented with varieties of mushrooms in an effort to find an inexpensive and available food supply for the poor Black families of the countryside. Benson also loved solving puzzles. On a challenge he solved the secret French code, the “Undecipherable Cipher,” in 1896 and informed the U.S. War Department that he had done so. He also offered to work for the military in solving enemy codes during the Spanish-American War (1898), but the United States prevailed without his help.

Benson achieved national recognition with his defense of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory manager, in one of Georgia’s most notorious instances of anti-Semitism. Frank was convicted, largely on the testimony of a janitor with a previous prison record, of murdering a thirteen-year-old factory worker in Atlanta. Benson noticed discrepancies in the janitor’s testimony and eventually convinced the janitor’s lawyer that his client had lied on the witness stand. Benson publicized his arguments in newspapers across the country and in a self-published pamphlet exonerating Frank. His findings were partially instrumental in persuading Governor John M. Slaton to commute Frank’s death sentence to life in prison.

Later Years

Still physically and mentally fit at age seventy-four, Benson, wearing his old uniform and carrying his unsurrendered rifle, led the Georgia Confederate Veterans Battalion in a 1917 review before U.S. president Woodrow Wilson in Washington, D.C. Newsreel cameras focused on Benson, whose image was shown in theaters nationwide.

When he learned about the plight of orphaned French children during World War I (1917-18), Benson “adopted” 5 of them and persuaded his friends to adopt 160 others. In exchanging dollars for francs during these proceedings he noticed that a person could buy francs cheaply in France and sell them at the official rate in the United States. In November 1919 he informed the U.S. attorney general that unscrupulous persons might take advantage of this discrepancy but was assured that such a thing would not happen. The following month, however, Carlos Ponzi, an Italian immigrant with a criminal record, began to exploit the difference in exchange rates by opening a bank in Boston, Massachusetts, and attracting millions of dollars from depositors hoping to get rich quickly. Benson learned of Ponzi’s activity and alerted the Massachusetts attorney general. Augusta newspapers credited Benson for initiating the investigation, which led to the imprisonment of Ponzi.

Benson remained active to the end, leading Boy Scouts on fifteen-mile hikes in the woods at the age of seventy-nine. He died on January 1, 1923. In 1962 his daughter-in-law Susan Williams Benson published portions of his war journal under the title Berry Benson’s Civil War Book.