In January 1957, following the successful bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama (1955-56), a group of Black ministers launched the Love, Law, and Liberation (or Triple L) Movement to desegregate Atlanta’s city buses. Under the leadership of the Reverend William Holmes Borders, the ministers staged a violation of the state law requiring segregation on common carriers, thereby securing the grounds for a legal challenge to the very foundation of Georgia’s Jim Crow architecture. Two years later, in January 1959, a federal district court ruled in favor of the ministers, ending more than six decades of segregation on Atlanta’s city buses.

Background

In the first half of the twentieth century, public space in Atlanta and throughout the South was strictly segregated. In order to avoid “intimate contact” between the races, local governments carved municipalities into separate spheres, creating, in effect, two distinct communities with few opportunities for social interaction. However, because it was prohibitively expensive to provide separate vehicles for each race, transit companies segregated buses and streetcars instead, requiring white passengers to sit from the front to the rear, and Black passengers to sit from the rear to the front.

To avoid the violence they believed would accompany interracial contact, state legislators invested transit conductors with expansive police powers when they passed the region’s first segregation statutes for streetcars in 1890. This precaution notwithstanding, interracial conflicts occurred with some frequency, and Atlanta’s bus drivers earned a reputation for resorting to violence upon the slightest breach of the color line. Following a particularly violent incident in 1943, the city’s bus drivers were deputized and armed with revolvers.

Despite frequent attempts, Black petitioners seldom received redress from city hall when bus drivers abused their powers. Conditions improved during William B. Hartsfield’s mayoralty (1937-1941, 1942-1961), but inadequate service and segregated seating remained subjects of controversy in the Black community. Isolated challenges on city buses achieved little success, and an organized movement of protest similar to the Montgomery bus boycott failed to develop. When the U.S. Supreme Court issued the decision that desegregated Montgomery’s city buses in November 1956, however, Borders and his ministerial colleagues resolved to appeal to the courts to force the desegregation of Atlanta’s public transportation system.

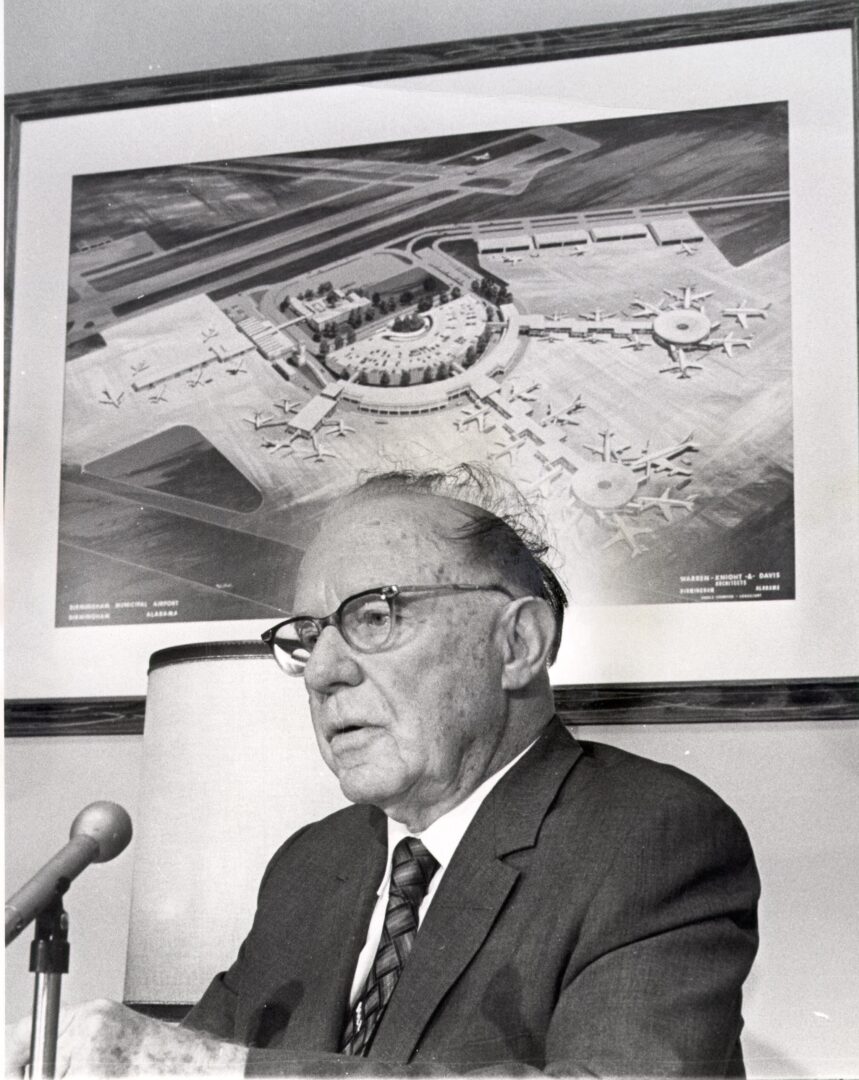

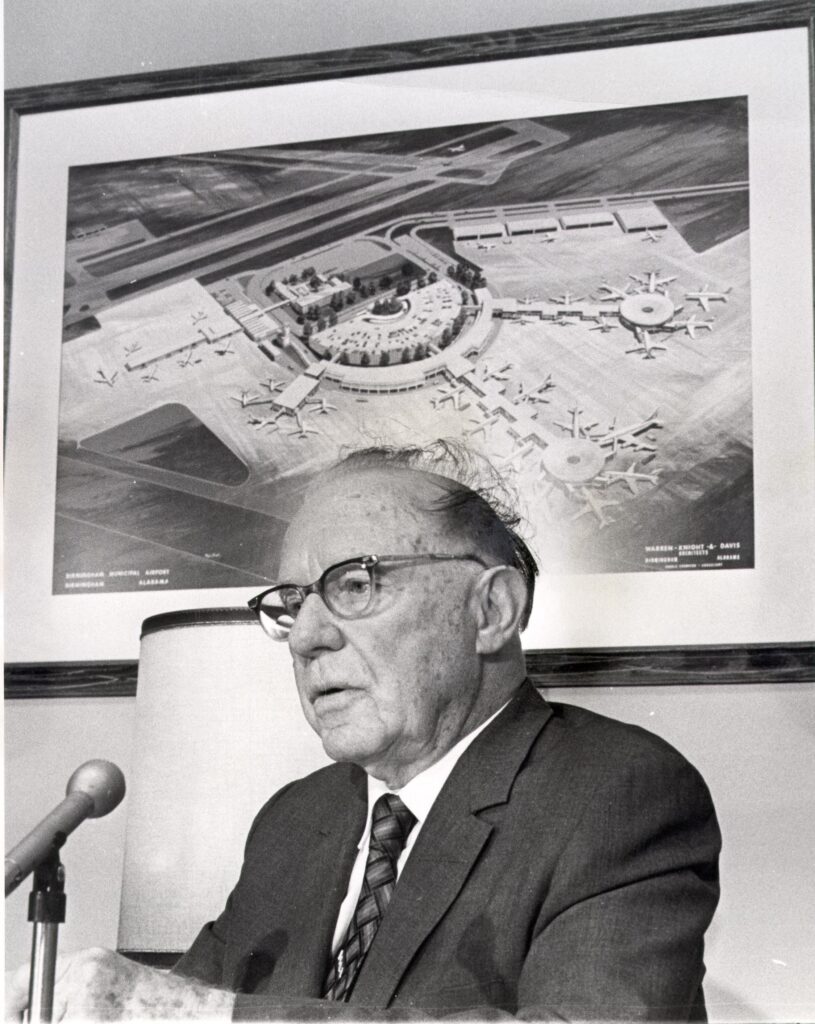

Courtesy of Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Securing a Test Case

On January 8, 1957, Borders announced the group’s plans to an audience of more than 1,200 people at the Wheat Street Baptist Church on Auburn Avenue. “We are going to ride until these buses are desegregated,” stated Borders. “If they take the bus to the barn, we’ll ride it to the barn and then get another. We’ll take every bus in Atlanta to the barn if necessary.”

Despite Borders’s bluster, the Triple L Movement was characterized as much by conservatism as by confrontation. Laypeople were not allowed to participate, and the ministers resolved never to sit beside other white passengers, particularly white women. Perhaps most importantly, the group notified Mayor Hartsfield of their plans in advance, to preclude the possibility of civil unrest.

The following morning, January 9, six ministers boarded a downtown bus at the corner of Mitchell and Whitehall streets and took their seats at the front of the vehicle. White passengers then exited, and after switching the sign to “Special,” the driver returned the vehicle to the barn, or the garage where the city’s buses were kept overnight. Upon hearing news of the event, Georgia governor and avowed segregationist Marvin Griffin placed state troops on alert and warned Atlanta residents that “riots, insurrections, and breaches of the peace” would not be tolerated. However, members of the Hartsfield coalition reacted more responsibly. Police chief Herbert Jenkins issued warrants for the ministers after first contacting Borders to determine a convenient time and place of arrest, and Mayor Hartsfield even offered to send limousines to take the ministers to City Hall, though Borders refused, insisting on the spectacle of a marked police car instead.

Photograph by Warren LeMay

News of the ministers’ ride traveled quickly throughout the city, and a large crowd of onlookers came to Wheat Street to witness their arrest the following afternoon. “The people knew why we were there, why the police were there,” Borders later recalled. “People quit work. They stopped cooking meals. They left beauty shops. They came out of stores. They thronged the streets.”

Outside the church, a crush of jubilant supporters pressed against the patrol car, impeding its forward progress. At the request of the arresting officers—one of whom was white and one of whom was Black—Borders stepped outside the vehicle and asked the crowd to disperse. “You’ve given us real joy,” he began. “We are strengthened in the knowledge you are with us, are supporting us, in this bus strike. There is, however, nothing more that you can do. We must go through with this arrest so that this injustice can be met and dealt with properly in the courts of this country, by attorneys. Thank you for coming. Now please go home. Pray for our success. But right now, let us be arrested as we have planned.”

The Verdict

On January 9, 1959, the federal district court in Atlanta ruled in favor of the ministers, citing as precedent the Browder v. Gayle decision that desegregated Montgomery’s buses in November 1956. However, rather than encourage Black passengers to immediately begin riding desegregated buses, Borders and his colleagues called for a cooling-down period, wherein the Black community’s ministerial leadership could confer with members of the Hartsfield administration to facilitate an orderly and peaceful desegregation process. Although numerous Black residents criticized the delay, Borders steadfastly defended the decision, saying it was “fair, wise, and courteous” to make arrangements first with Hartsfield and other members of the white power structure.

After nearly two weeks of waiting, Borders announced on January 20 that the time had come. He told an audience of 2,500 at the Wheat Street Baptist Church to “sit where you want to on the buses and trolleys,” but still urged Black commuters to comport themselves with dignity and modesty. Specifically, he cautioned Black men to “use good judgment: don’t sit down by any white women at all.”

As officials with the Atlanta Transit Company had feared, white ridership declined precipitously following the court’s decision. According to a survey taken in 1960, Blacks accounted for almost 60 percent of the city’s bus patronage during the rush period, despite representing only a third of the city’s total population. While this figure reflected the higher incidence of automobile ownership among white residents and the peculiarities of Atlanta’s residential landscape, it also indicated a growing willingness among white residents to abandon the city’s public space altogether and foreshadowed the role that race would play in the debates over the city’s Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority a decade later.