Located in Effingham County about twenty-five miles northwest of Savannah on the banks of Ebenezer Creek, Ebenezer was one of Georgia’s original settlements and was Effingham’s county seat from 1797 to 1799.

Established in 1734 as a military defense for Savannah, Ebenezer (meaning “stone of help” in Hebrew) was the recipient of Georgia’s first religious refugees. The original colonists emigrated from Salzburg in central Europe (present-day Austria), from where they were expelled in the early 1730s for their religious beliefs. General James Oglethorpe offered the persecuted Protestants refuge in the new colony.

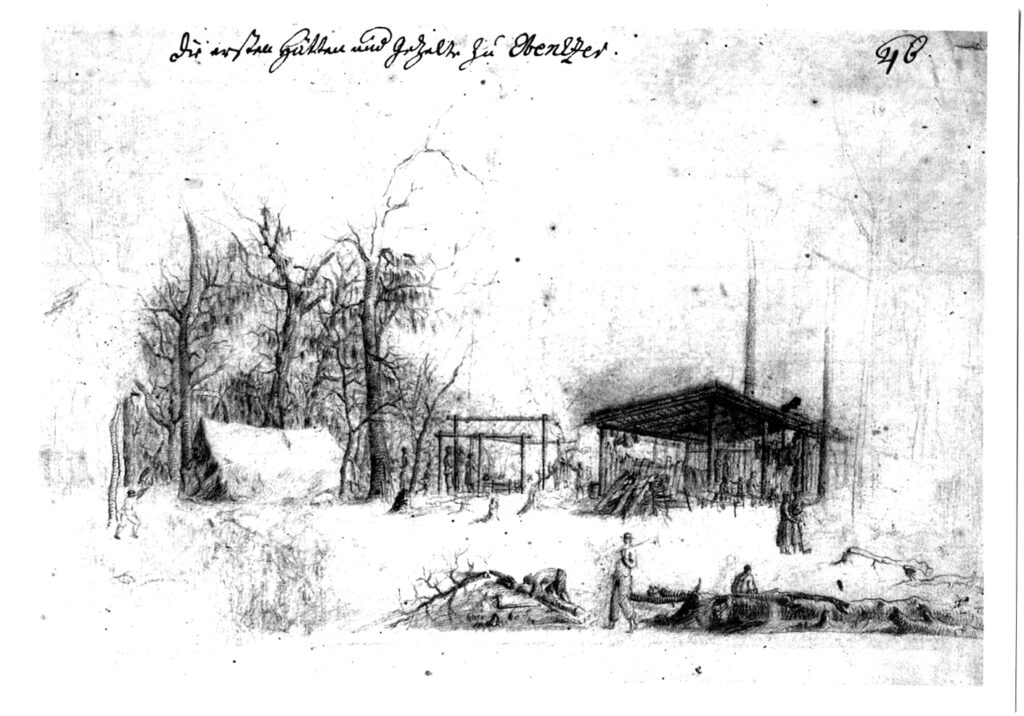

Although their numbers were never great, the residents of Ebenezer, known as the Salzburgers, provided the Trustees of Georgia with some of their strongest and most enduring support. As such, the Salzburgers were influential in shaping the original laws and character of the colony. Because most of the town’s residents did not speak English and the local civil authority was controlled by religious leaders, Ebenezer was also one of the more isolated communities in colonial Georgia. In 1736 the settlement was moved nearer the Savannah River to better land. Disease, including malaria, proved a problem at both locations, but New Ebenezer prospered with a silk operation, mills, and numerous houses.

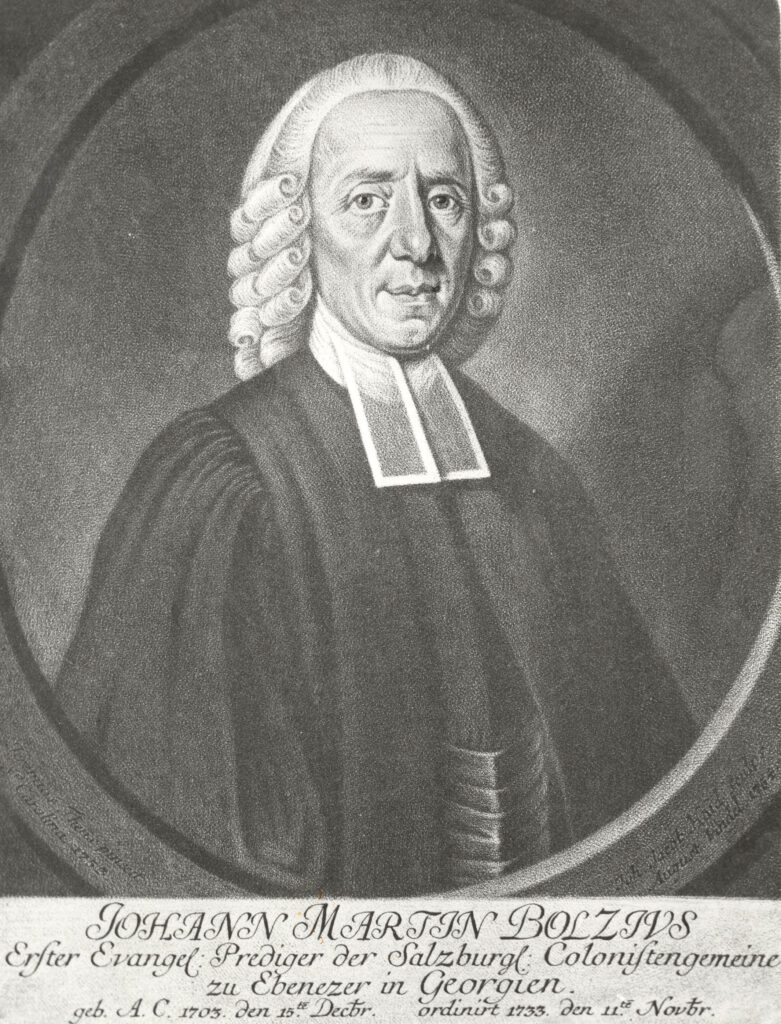

Led by pastor Johann Martin Boltzius, the people of Ebenezer attempted to build a religious utopia on the Georgia frontier. Boltzius believed he could build a spiritually pure and economically successful colony in a manner unlike other southern towns. He believed they should avoid the system of slavery and plantation agriculture. After a decade, the residents began producing silk from mulberry trees and built a successful mill to supplement income earned from the Indian trade. In addition, Ebenezer became an area where other religious refugees, such as the Moravians, chose to settle.

Because the Salzburgers maintained a degree of stability and economic prosperity, they became ardent defenders of the Trustees’ ban on slavery and limited land ownership. When groups like the Malcontents called for changes in the colony’s leadership, the people of Ebenezer argued that the Trustees had a progressive but sound vision for Georgia. Many Salzburgers believed that in order to realize their goal of building a religious utopia, they needed the social utopia promised by the Trustees. Thus, criticisms directed at the colonial leadership became criticisms of the Salzburgers as well.

When the Trustees lost the support of a majority of Georgians, Ebenezer lost much of its influence in colonial politics. The Trustees lifted the ban on slavery in 1750, and the leadership of Ebenezer finally admitted that their settlement, based on small farms, trade, and industry, could not compete with plantation agriculture or enslaved labor. In addition, Ebenezer’s isolation would gradually change as land speculators scoured the countryside for land on which to grow their cash crops.

Although the Salzburgers played a prominent role in the affairs of Ebenezer throughout the colonial era, the decision to allow slavery forced the settlement to change. Furthermore, after the Trustees lost their charter in 1752 and Georgia became a royal colony, the Salzburgers lost their most powerful allies. Consequently, their influence in Georgia politics waned.

Because of Ebenezer’s strategic location in the defense of Savannah, it changed hands several times during the American Revolution (1775-83). The state of Georgia established a magazine there, and after the British invasion in 1778, British forces heavily fortified the town with redoubts.

The fighting left the town in ruins, and it never fully recovered. The county seat moved to Springfield in 1799, and Ebenezer steadily declined until it had all but disappeared by 1855. The town’s Jerusalem Church (later, Jerusalem Evangelical Lutheran Church), finished in 1769, still stands. It is one of the few Georgia buildings to survive the Revolutionary War. John Adam Treutlen, Georgia’s first state governor, lived in Ebenezer.