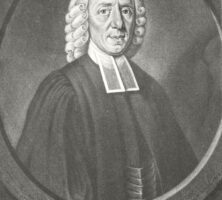

Johann Martin Boltzius (sometimes spelled “Bolzius”) was senior minister to the Salzburger community at Ebenezer for three decades (1735-65) and was largely responsible for its success. He was a vigorous opponent of slavery during the formative years of the Georgia colony.

Education and Early Career

Boltzius was born on December 15, 1703, in Forst, Germany, southwest of Berlin. His parents, Eva Rosina Muller and Martin Boltzius, earned a modest living as weavers. Young Boltzius won a theology scholarship to the University of Halle (later Martin-Luther-University of Halle-Wittenberg) in Halle, Germany. There he studied Lutheran Pietism, which emphasized salvation by grace, strong ethics, vigorous pastoral leadership, and social compassion. Boltzius then briefly served as inspector of the Latin School of the Francke, or Halle, Orphanage Foundation, an institution that provided charitable services and encouraged Protestant education.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Gotthilf August Francke, cofounder and professor of the University of Halle, selected Boltzius to serve as senior minister to the Salzburg Protestant refugees who journeyed to Georgia in the fall of 1733 to escape the repressive policies of Catholic archbishop Count Leopold von Firmian. A younger associate, Israel Christian Gronau, accompanied Boltzius. To cement relations with their new charges, Boltzius and Gronau married two Salzburg sisters in the Georgia settlement.

Salzburger Community

Boltzius envisioned a thriving community that emphasized Christian principles, a strong work ethic, practical business sense, and economic diversity. To accomplish his goals, he mastered English to work with British officials and learned the Salzburg form of German to teach Pietistic principles to his communicants. Boltzius stressed that God governed the community through appointed ministers who handled disciplinary and administrative affairs. When necessary, he submitted to the Trustees’ authority but generally insisted that the Salzburgers maintain a semi-independent status within the colony.

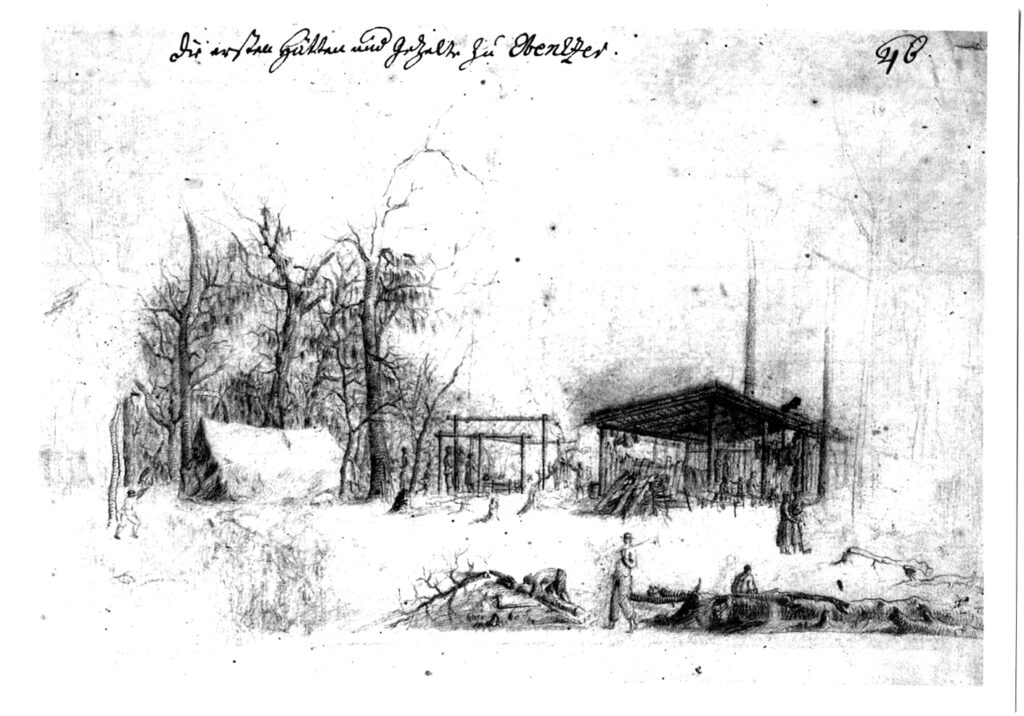

Boltzius openly admired James Edward Oglethorpe, who represented the Trustees’ authority in Georgia, and readily accepted his selection of Ebenezer as the Salzburger settlement. But the first few years proved fraught with problems. Residents experienced crop failures. They succumbed to malaria, dysentery, typhoid, and other ailments. Infants rarely survived the first few months. At first Boltzius interpreted the hardships as forms of religious testing, but over time he blamed Oglethorpe for selecting a poor location. In 1736, when Georgia’s leader insisted that the Salzburgers remain at their original settlement for defense purposes, Boltzius confronted Oglethorpe with a harsh but successful ultimatum: either they receive permission to relocate to the Red Bluff on the Savannah River, or they would disband and leave the colony. Oglethorpe allowed the Salzburgers to move to the Red Bluff, where they established New Ebenezer.

Print from Von Reck Archive, Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen

Boltzius always sought the best for the Salzburgers, but he found himself acting more as an administrator than a minister. He understood the advantages of private enterprise over communal efforts and repeatedly advocated that policy to the Trustees. He urged the adoption of new agricultural technology and helped the community to construct a gristmill, a rice mill, and a sawmill to supplement their funds. Both he and Gronau encouraged their wives to experiment with the cultivation of black and white mulberry trees to help the women of Ebenezer develop a small-scale silk production. While the Salzburgers generally loved their senior minister, opportunities for personal independence in Georgia gradually reduced their deference to his authority. At times, Boltzius also faced opposition from non-Salzburg residents who argued with his theology and denied his ministerial leadership.

Expansion and Slavery

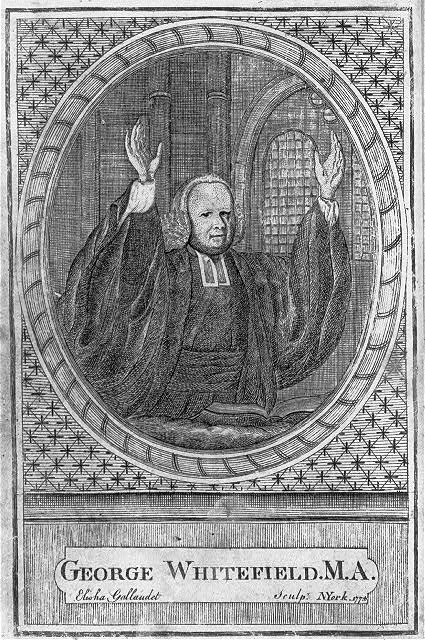

Boltzius sought to extend his ministerial influence throughout Georgia. Many German Lutherans moved to New Ebenezer, but Boltzius was less successful in attracting those of the Calvinist Reformed tradition. He refused to fully accept the Moravians but formed a strong friendship with George Whitefield, Georgia’s Anglican minister. He expressed particular delight in his contacts with native and Jewish residents of the colony. Boltzius interpreted their willingness to give aid to the Salzburgers as an indication of their receptiveness toward the gospel, but when both groups disappointed Boltzius’s expectations, he soon revised his attitude toward them.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Boltzius was outspoken in his opinions about issues that affected the colony. He reluctantly supported Oglethorpe’s 1740 attack against St. Augustine because he thought it an aggressive, unnecessary attack and because he remembered the horrors of war in Europe. Boltzius insisted upon servants’ deference to their masters to maintain a God-ordained social order, a policy that frequently placed him in conflict with indentured German servants who argued with their Trustee employers.

Yet Boltzius vigorously opposed slavery as a violation of his Christian values, work ethic, economic pragmatism, and enlightened sense of rational reform. The colony’s proslavery group, the Malcontents, angrily accused Boltzius of tyrannically forcing his opinions upon the Salzburgers. They sought to remove him by writing letters of complaints to British and German supporters of the New Ebenezer settlement. The effort proved divisive, and for a time Boltzius feared that the Malcontents might take his life. By the late 1740s Boltzius reluctantly concluded that he must accept slavery or risk losing the Salzburg settlement because of a labor shortage. He compensated by looking upon slavery as a new field in which to spread Christianity. In time, he too enslaved Black laborers.

Later Career

Boltzius frequently sent correspondence and reports to Samuel Urlsperger, senior Lutheran minister in Augsburg; the Trustees; and the Francke Foundation. His letters and travel diary, both in German and English, reveal detailed observations about his ministerial duties, his administration, and the worship practices of the Salzburgers. Urlsperger published these reports for European evangelical Protestants, but he frequently expunged the most sensitive and negative parts, particularly of those written in 1744 and 1745. He removed comments relating to the fight over slavery in the colony and other sensitive material that he feared might hinder financial support for both Ebenezer and the Francke Foundation.

As he grew older, Boltzius lost much of his eyesight and continued to suffer from malaria contracted earlier in his Georgia career. When Gronau died in early 1745, Boltzius began to delegate his responsibilities among Lutheran assistants sent by supporters and civil appointees of the Trustee and royal governments. In 1751 he received a 500-acre grant near Goshen, southeast of Ebenezer, which he called Good Harmony, but he never made a serious effort to develop it. He claimed that the Salzburgers required his energy and time more than did a plot of ground. He died at New Ebenezer on November 19, 1765. The community suffered from the absence of his guidance and firm direction.