The British actress and writer Fanny Kemble’s infamous entanglement with Georgia began in the 1830s when she married Pierce Mease Butler, who in 1836 inherited his grandfather’s legacy, including hundreds of enslaved Africans and several plantations on the Sea Islands.

Frances Anne Kemble was born in 1809 into the first family of the British stage. After her debut in 1829 at Covent Garden in London, England, where she triumphed in the role of Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, she became an icon of the British stage; she achieved international stardom on her tour up and down the East Coast of the United States in the fall of 1832. She retired from her theatrical career after marrying Butler in June 1834 but hoped to pursue her literary interests. She became a best-selling author when her Journal of Frances Anne Butler appeared in 1835, and the book scandalized American readers with her candid assessments of her adopted country.

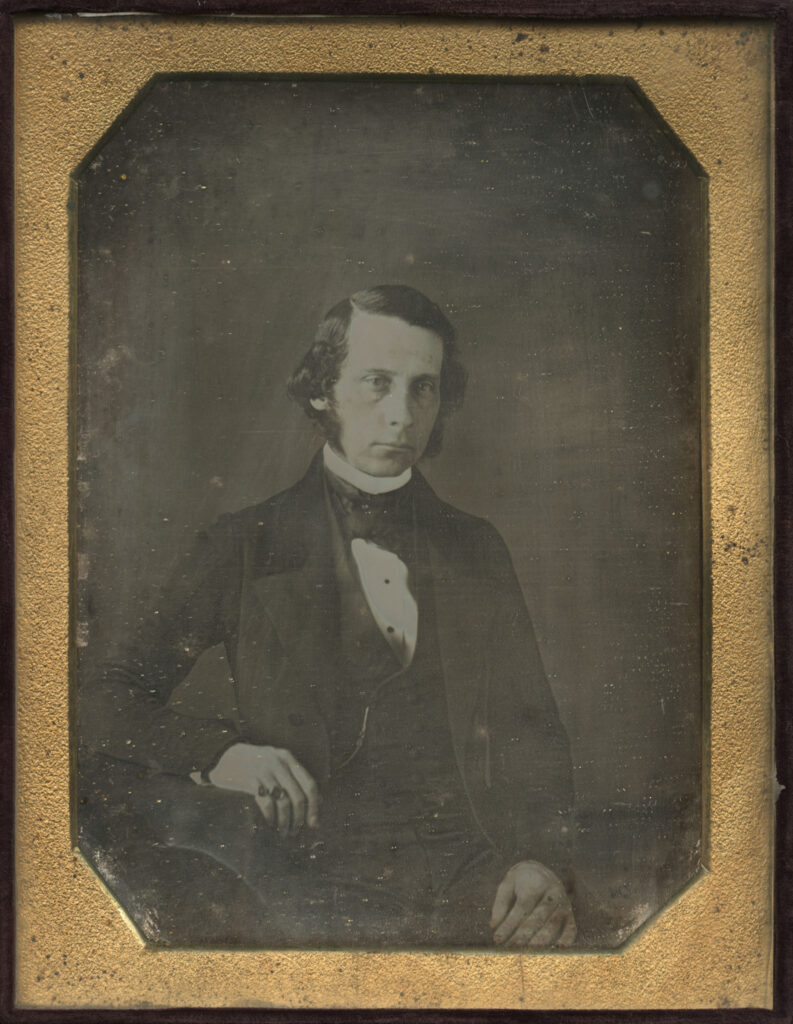

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

In December 1838 Kemble accompanied her husband and two young daughters to Butler’s vast holdings on St. Simons and Butler’s islands. Butler took his wife south despite her moral opposition to slavery, hoping a visit would rid her of her abolitionist bent. It was a miscalculated attempt: during the winter of 1838-39, Kemble’s diary became an impassioned eyewitness account of the wrongs of slavery. A devoted diarist, Kemble also offered commentary on fellow planters, as well as the flora and fauna of the islands, but her most acute observations involved her encounters with enslaved people.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Kemble’s riveting account of the men, women, and children her husband enslaved provides gripping insight on life in the antebellum South. As the wife of a planter, Kemble had unimpeded access to plantation affairs and was especially poignant and pointed when she allowed the voices of enslaved women, so seldom heard during this era, to shine through in the pages of her journal. Kemble’s battles with Butler over the harsh treatment of the people he enslaved contributed to the couple’s permanent impasse, which resulted in marital separation in 1845 and a divorce in 1849.

Although abolitionists encouraged Kemble to publish the vivid diary of her days in Georgia, she resisted their entreaties for more than two decades, so as not to antagonize Butler, who maintained custody of their two daughters until they came of age. During the Civil War (1861-65), Kemble became alarmed about foreign attitudes toward the Confederacy and published her Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839 in England in 1863. This book—an Englishwoman’s dramatic condemnation of the evils she had witnessed, the plantation life she had lived—caused a sensation as well. Although some have tried to credit this book with dissuading the British from official recognition of the Confederate States, it is clear that Kemble’s Georgian journal had a larger impact on general readers than on diplomatic decisions.

White southerners vilified the book; some continued to discredit Kemble’s account for more than a hundred years. Margaret Davis Cate, for example, published a scathing critique in the Georgia Historical Quarterly in 1960. Despite this campaign, the journal has become a classic and a reliable source for scholars investigating plantation life. Kemble’s descriptions of Georgia revealed her ambivalent attraction to the state, as she confessed, “I should like the wild savage loneliness of the far away existence extremely if it were not for the one small item of 'the slavery.'” But it was this “one small item” that became a bone of contention between Kemble and Butler; and later Kemble and her younger daughter, Frances Butler Leigh, had bitter and protracted disagreements over this issue. (Indeed, Leigh wrote her own memoir of the region, published in 1883, Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation, which was intended as a direct refutation of many of her mother’s claims about race relations.) Kemble’s older daughter, Sarah, married Owen Jones Wister, a doctor from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Their son, Owen Wister, later wrote The Virginian [1902].)

Kemble eventually moved to Philadelphia, where she supported herself by touring the United States and Europe with her Shakespeare readings. She continued to travel until her death on January 15, 1893, in London.

Today the plantations Kemble wrote about reflect the diversity of the region: the former estate on Butler’s Island has been turned into a state wildlife preserve; another patrimonial home on St. Simons has been obliterated by development, absorbed on the grounds of a marina; and Little St. Simons Island remains in the hands of the family that bought the land from Fanny Kemble’s daughters and is now a luxury resort. These islands are dotted with reminders of this remarkable nineteenth-century woman and the mark she left on this remote corner of Georgia.