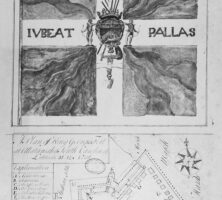

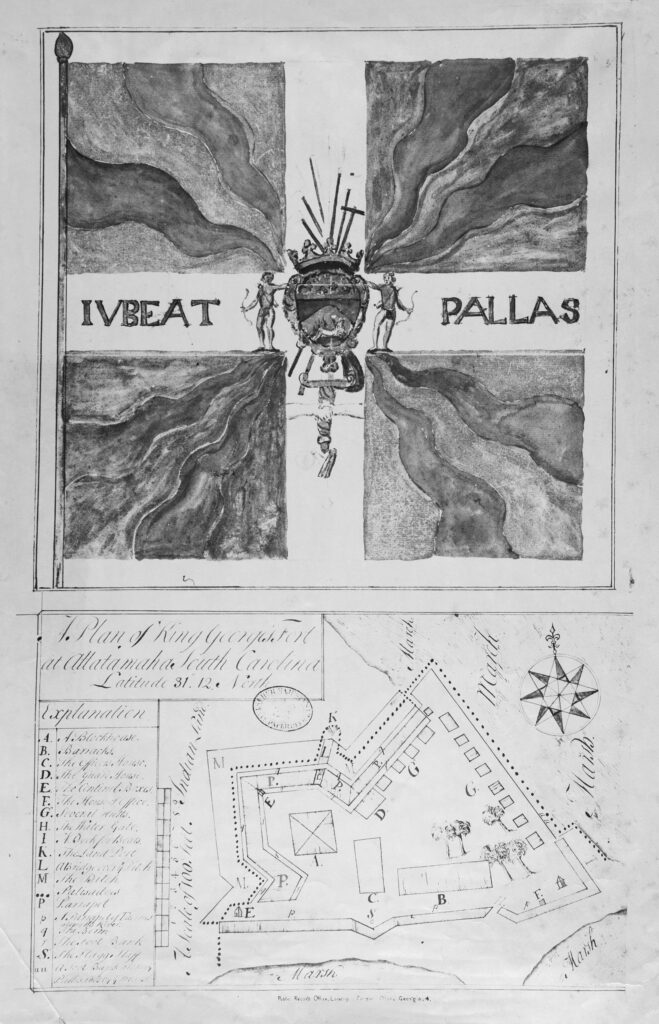

Fort King George, the first British garrison of the Georgia colony, is located in Darien, at the mouth of the Altamaha River. Established in 1721 as the southernmost outpost of British North America, the post became the stronghold for the coveted southeastern region.

Garrisoned from 1721 to 1732, Fort King George was built under the command of Colonel John “Tuscarora Jack” Barnwell and manned by His Majesty’s Independent Company of Foot. Destroyed by fire in 1726, the fort was rebuilt the following year and guarded by the colonial company until 1732. The present Fort King George, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, includes an authentically reconstructed blockhouse, the remains of the old sawmill, and one of the oldest British military cemeteries in the Southeast.

Historical Background

Throughout the 1600s and early 1700s, the land along the Altamaha River, now a part of Georgia, was one of the most coveted territories in North America. An area of rich natural resources and accessible waterways, the British claimed it as the southernmost part of their South Carolina colony. The Spanish regarded this claim as an obstacle to their mission of expanding their empire and Christianizing the natives in the New World. The French viewed control of the Altamaha as an opportunity for the eastward expansion of their empire while blocking Britain’s advance southward. Due to these imperial threats, as well as possible attacks by now-hostile Guale Indians, the British, under the direction of Colonel Barnwell and Governor Francis Nicholson of South Carolina, established Fort King George in 1721.

Courtesy of Fort King George

The Fort and His Majesty’s Independent Company

Built on the northern bank of the Altamaha River, the original fort was a triangular-shaped earthen fortification consisting of moats, palisades, barracks, and a twenty-six-square-foot blockhouse. Constructed by Barnwell’s scouts, the cypress-log blockhouse consisted of three levels—a powder, ammunition, and supply storage room on the lower level; a gun- and cannon-port room on the second floor; and a lookout post on the third floor.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Finding soldiers to garrison the fort proved as challenging as the construction. As the British colonies expanded during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and conflicts with neighboring countries began to increase, so did the need for more reinforcements. Although both Barnwell and Nicholson had requested only the “best,” fit and spry young soldiers, to man their new fort, they were sent “invalids” from the Royal Hospital at Chelsea, England. Based on a welfare system that provided government-subsidized hospital care and pensions, the British army was able to create a Regiment of Invalids. Once veterans, classified as either in-pensioners or out-pensioners, were designated as out-pensioners, they were available for light duty, including the manning of small forts.

In 1721 a small company of 100 privates and several officers, known as His Majesty’s Independent Company of Foot, were sent from the Regiment of Invalids to Port Royal, South Carolina. The harsh journey, compounded by poor diet, resulted in the delivery of ailing soldiers, half of whom had contracted scurvy during the voyage. In May the regiment arrived not at the fort but at a hospital in Port Royal, where the soldiers spent the rest of the year. In 1722 the surviving members of the regiment left the hospital and moved on to the fort.

Darien

Due to poor living conditions, a mysterious fire in 1726, and the eventual abandonment of the site by 1732, Scottish Highlanders were sent to Georgia in 1736 to establish a new outpost. Under the leadership of General James Oglethorpe, these men established the settlement of Darien and a sawmill along the Altamaha. The sawmill was the beginning of what was to become a large-scale lumber industry for Darien, from the early twentieth century until 1925. Milling in the vicinity may have destroyed the remains of the original fort.

Courtesy of Fort King George

In 1988 Fort King George was rebuilt as an authentic replication of the original post. The blockhouse, a forty-foot-high building, was constructed as an accurate representation of the initial structure, according to the original plans obtained from the British Public Records Office in London, England. The historic site now comprises a museum, a blockhouse, barracks, and a cemetery, which holds the graves of seventeen British soldiers who died while in service at the fort.