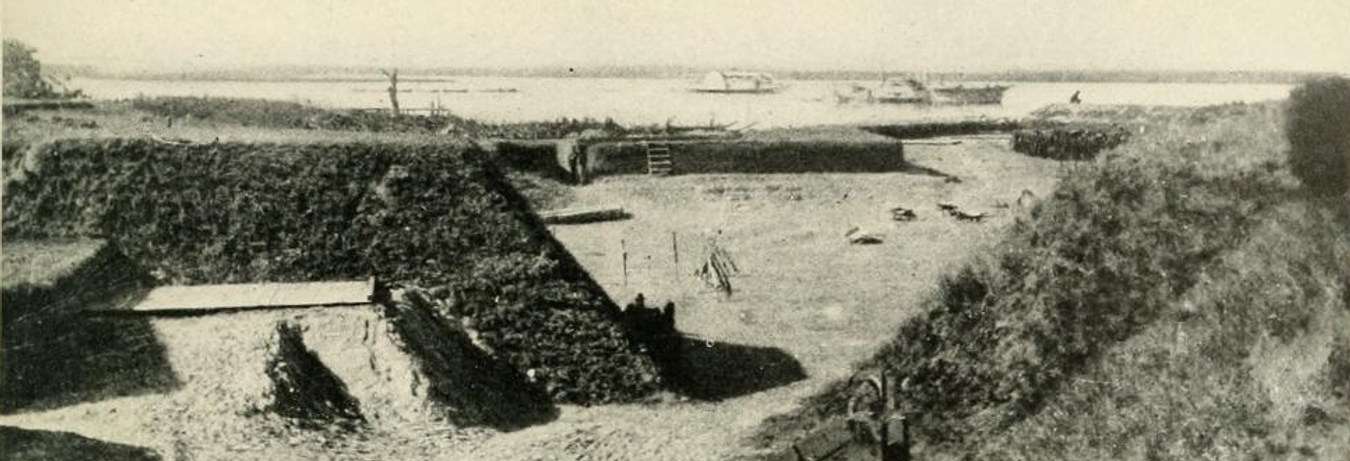

Fort McAllister was a Confederate earthwork fortification near the mouth of the Ogeechee River in Bryan County. The fort played an important role in the defense of Savannah during the Union navy blockade of the Georgia coast.

Built in 1861 at Genesis Point, the fort was constructed on the plantation of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Longworth McAllister, for whom it was named. Fort McAllister provided protection from the U.S. Navy for the southern flank of Savannah, about fifteen miles to the north, during the Civil War (1861-65). It also afforded defense for the productive rice plantations of the lower Ogeechee River basin, and for the Savannah, Albany & Gulf Railroad Bridge, a key transportation link, farther upriver.

Photograph from Wikimedia

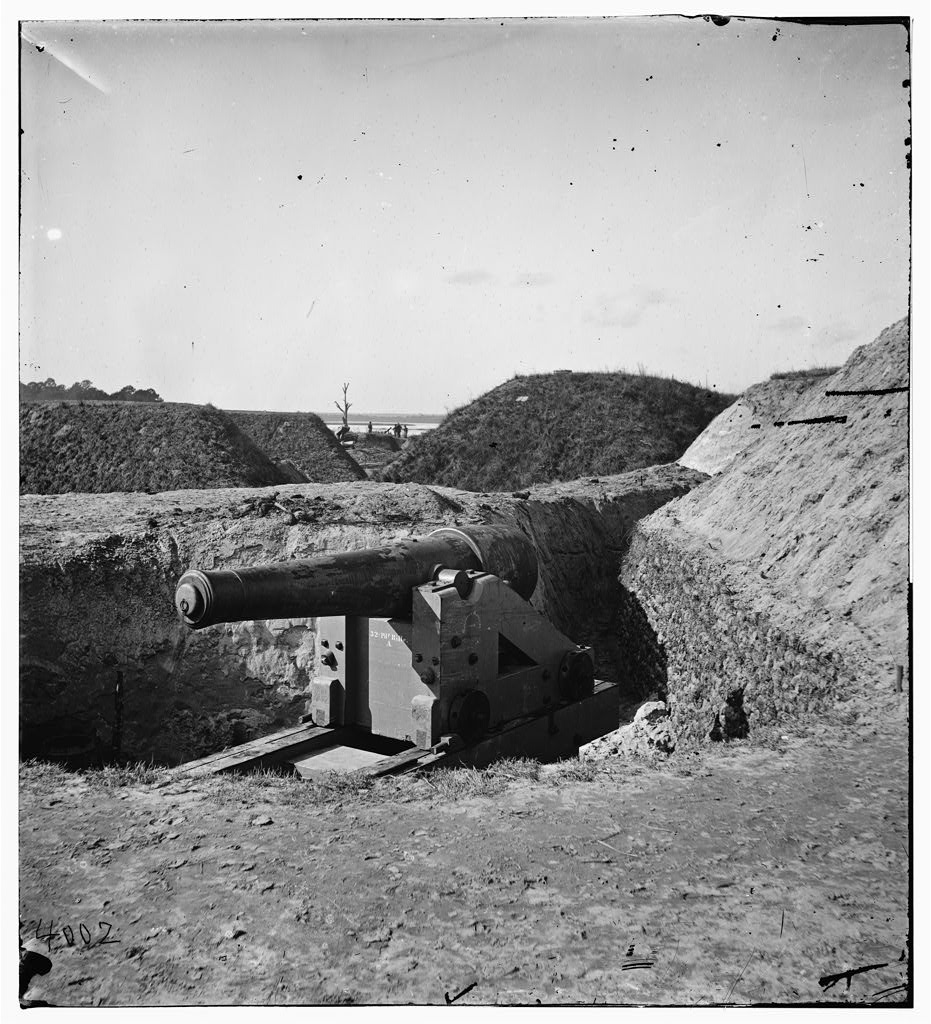

The earthworks were designed by military engineers to absorb considerable punishment from Union bombardment. The fort was built chiefly for defense against naval attacks, rather than against a landward assault. Fort McAllister had ten large-caliber guns and facilities for the heating of “red-hot shot,” cannonballs that, when striking their targets, could set wooden warships ablaze.

During 1862 and 1863, Fort McAllister repelled seven Union naval attacks by elements of the blockading forces offshore and in nearby Ossabaw Sound. Several of these attacks were made by the latest in naval warship technology, including the ironclad monitors USS Montauk and USS Passaic. One of the casualties of the Union assaults was Major John Gallie, Fort McAllister’s commanding officer. The fort sustained damage to its earthwork walls, but the guns of Fort McAllister managed to drive off the Union attackers each time they came upriver to bombard the fort. Blasted sections of the fort were quickly replaced with dirt and marsh mud.

Photograph from Wikimedia

In early 1863 the Confederate blockade-runner, CSS Rattlesnake (formerly the CSS Nashville) took refuge in the Ogeechee River. After taking on a load of cotton, it was grounded on the mudflats not far from Fort McAllister. Union gunboats proceeded to fire on the Rattlesnake at long range across the marsh and eventually set her on fire. The Confederate vessel and its cargo were completely destroyed.

Fort McAllister never fell to Union naval forces because of its unique earthen construction. This was in sharp contrast to the much larger and supposedly impregnable Fort Pulaski at nearby Cockspur Island, which fell after less than thirty-six hours of bombardment by Union forces using newly developed rifled artillery. (Rifling, or the addition of spiral grooves within a gun’s barrel, made these weapons especially effective against Fort Pulaski’s masonry fortifications.)

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

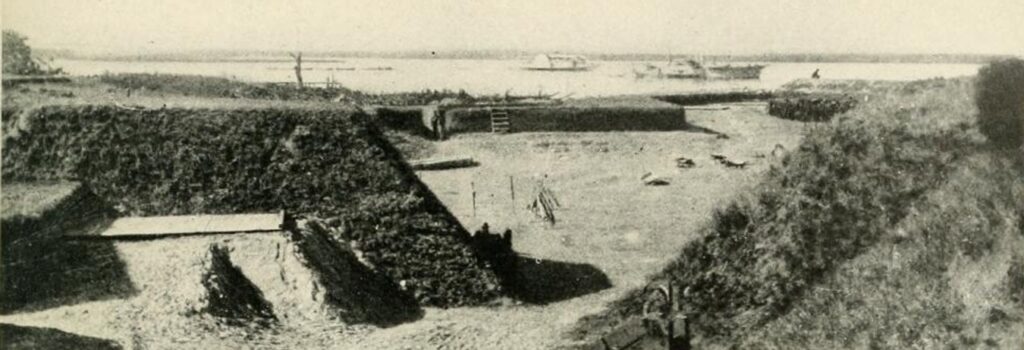

Elements of the right wing of Union general William T. Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee crossed the Ogeechee River in early December 1864, near the end of its March to the Sea. Sherman’s orders to Major General O. O. Howard were to capture Fort McAllister from the landward side, so that the Union army might be resupplied from navy transports anchored offshore. Reduction of Fort McAllister would also open the “back door” to Savannah for Sherman’s forces.

The Union land assault on Fort McAllister on December 13, 1864, overwhelmed the heavily outnumbered Confederate defenders in a brief, but very intense, battle of fifteen minutes. Federal infantry poured across the narrow causeway linking Genesis Point with the mainland, despite the mining of the approaches to the fort by the Confederates. Sherman observed the successful attack from a vantage point atop the rice mill of the Cheves Plantation across the river. Following the surrender of Major George W. Anderson’s force, Sherman and members of his staff landed at Fort McAllister by boat, and they made contact with the Union naval forces in Ossabaw Sound.

Photograph by Wikimedia

For the remainder of the war, Fort McAllister served as a prison for Confederate soldiers captured on the upper Georgia coast. After the war, the fort fell into ruin and remained so until the late 1930s, when it was restored as a historic site for the public through funding provided by Henry Ford, who owned the property at that time. Fort McAllister is now maintained by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as a state historic park, with a museum, guided tours, and interpretive programming.