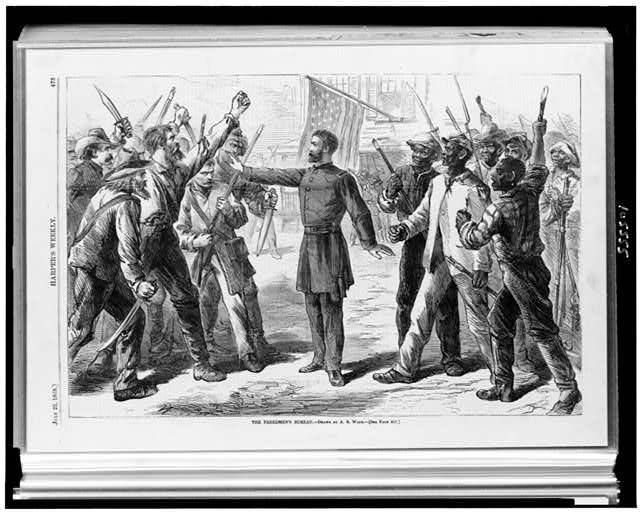

In March 1865 the U.S. Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands to aid African Americans undergoing the transition from slavery to freedom in the aftermath of the Civil War (1861-65).

The Freedmen’s Bureau, as it was more commonly known, was the first organization of its kind, a federal agency established solely for the purpose of social welfare. Under the direction of Major General Oliver O. Howard, the agency furnished rations to refugees and freedpeople displaced by the war, established freedmen schools and hospitals, supervised the development of a contract labor system, and created military tribunals to adjudicate legal disputes. Though operations ceased in Georgia and other states as early as 1870, the bureau remained a functioning federal agency until 1872, when Congress allowed its authorization to expire.

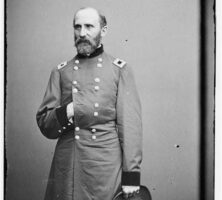

On May 20, 1865, Howard appointed Brigadier General Rufus Saxton to oversee the bureau’s efforts in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Saxton had spent the better part of the war on the Sea Islands of South Carolina as part of a Union occupation force that supervised abandoned plantations and their African American residents. As the bureau’s assistant commissioner, he largely continued his wartime efforts, encouraging freedpeople to resettle on abandoned or confiscated properties and touting land acquisition as an essential step on the path to self-sufficiency.

Labor

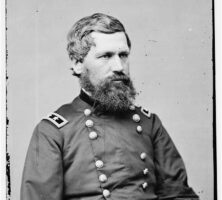

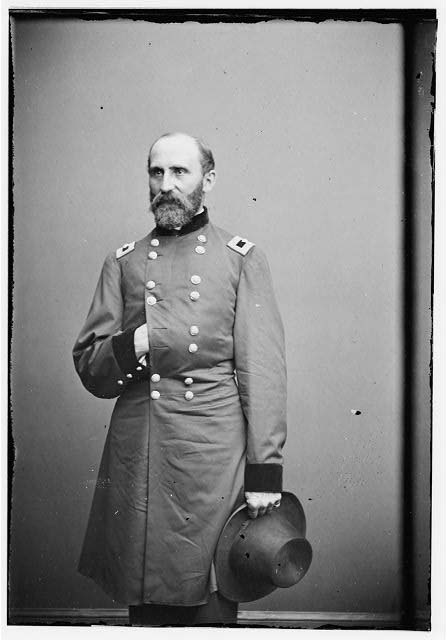

Saxton’s advocacy of free labor and written contracts helped shape the bureau’s efforts for years to come, but he struggled to bring order to the state’s inland territories and in September 1865 was relieved of his command in Georgia. The bureau’s presence expanded under Saxton’s successor, Brigadier General Davis Tillson, and by September 1866 the agency had doled out more than 800,000 rations statewide. While a majority of the agency’s rations went to freedpeople, a surprising number of poor whites benefited from bureau relief measures as well. In Georgia whites received almost one-fifth of the agency’s rations; regionwide, whites received more than a fourth.

Though not insensitive to freedpeople’s aspirations, Tillson was unmoved by the spirit of egalitarianism that characterized his predecessor’s administration. Above all else he prized stability, particularly with regard to labor and occasionally at the expense of the freedpeople’s interests. On Tillson’s order, healthy adult males were denied rations to promote self-sufficiency, and bureau officials were instructed to vigorously enforce the state’s vagrancy laws, which allowed authorities to pair indigent or idle workers with employers in need of labor.

Tillson meanwhile solicited support from white Georgians, most of whom were initially hostile to the bureau’s efforts. His proposal to enlist white community leaders as bureau agents received support from delegates attending the state’s constitutional convention in October 1865, thereby conferring a measure of legitimacy on bureau policies while also swelling the agency’s understaffed ranks.

He reinforced the agency’s commitment to free labor as well, instituting uniform contracts for agricultural work and a wage scale to ensure that freedpeople enjoyed sufficient compensation for their labor. In upper and middle Georgia, male hands were to receive $12 to $13 per month and female hands were to receive $8 to $10 dollars per month in addition to food and lodging; the rates were slightly higher along the coast and in the fertile fields of southwest Georgia. When planters lacked sufficient cash to pay their workers, they were permitted to pay a share of the crop at the end of the season, an arrangement that anticipated the sharecropping and tenancy systems that characterized the state’s agricultural economy for the better part of the next century. (Other forms of tenancy existed during the antebellum era.) Many planters resented federal intrusion into their affairs, however, and despite the efforts of the bureau’s field officers, the agency never achieved full compliance.

Land

If contract reform was Tillson’s most constructive contribution to the bureau’s experiment in Georgia, land restoration was arguably his most memorable. In January 1865, as the Civil War neared its end, Union general William T. Sherman issued his famous Field Order No. 15, which granted possessory title of abandoned lands along the southern coastline to formerly enslaved African Americans. Freedmen worked the land on Sherman’s reservation until the fall of 1865, when U.S. president Andrew Johnson overturned Sherman’s order and instructed bureau officials to arrange “mutually satisfactory” agreements between planters and freedpeople holding competing claims to coastal properties.

Though bureau agents in Georgia moved slowly in hopes that Congress might intervene, the unenviable task of restoring coastal land to its original owners ultimately fell to Tillson. At the behest of African American bureau agent Tunis Campbell, headquartered on St. Catherines Island, many freedpeople resisted the agency’s efforts, but by the summer of 1866 land restoration was all but complete. Later legislation allowed a modest number of Georgia’s freedpeople to exchange legitimate land grants for warrants guaranteeing smaller parcels of land in South Carolina, but most had little choice but to work for their former enslavers, and many lost faith in their northern benefactors.

Reorganization

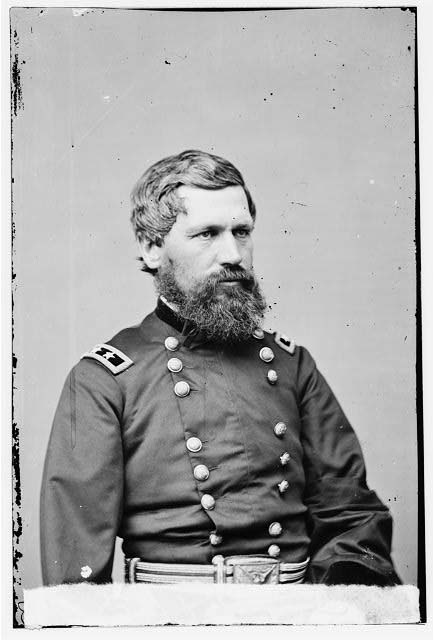

When Tillson retired from the agency in January 1867, Howard appointed Colonel Caleb C. Sibley to assume control of the bureau’s efforts in Georgia. To improve efficiency and accountability, Sibley reorganized the Georgia agency into ten subdistricts shortly after taking office, and appointed salaried army officers to oversee the agency’s work in each locale.

Sibley’s reorganization imposed a degree of order on the unwieldy agency, but corruption persisted among rank-and-file agents despite his reforms. Under Tillson’s administration civilian agents had collected fees from planters when sanctioning labor contracts with freedmen, an arrangement that relieved the financially distressed agency of onerous labor costs but also fostered corruption among agents whose sympathies lay with planters rather than the bureau. At the behest of officials in Washington, D.C., Sibley abolished the fee system and relieved the vast majority of civilian agents of their duties.

Apart from those structural reforms, Sibley largely maintained the course set by his predecessors until October 1868, when he retired from the agency. His successor, Colonel John R. Lewis, inherited a leaner organization with fewer agents and dwindling resources but nonetheless carried on the bureau’s work energetically, particularly in the field of education.

Education

Due to its limited resources, the Georgia bureau worked closely with northern benevolent societies to provide educational opportunities for tens of thousands of freedpeople statewide. The bureau most often provided logistical support and funds for the construction or purchase of school buildings while benevolent societies shouldered a majority of the teaching costs. Freedmen were expected to contribute funds as well, both to offset financial shortfalls and to foster a sense of ownership that would survive the agency’s presence.

In the first year alone, this arrangement provided for the establishment of more than sixty schools, and by 1868 teachers at bureau-sponsored schools had taught some 30,000 freedpeople to read. Even as other projects were winding down, Lewis reinforced the bureau’s commitment to education, stepping up oversight and assistance and encouraging the organization of local education societies capable of administering freedmen schools long after the bureau’s closure.

When Lewis left the agency in April 1870 to become the state’s first school superintendent, the bureau’s work was all but over in Georgia. The bureau’s initial charter lasted for only one year, but Congress extended its authorization in 1866; it remained a federal agency until 1872, though operations in Georgia and other states ceased by 1870.

Along with insufficient resources and white intransigence, the agency’s indefinite future at times stymied its effectiveness and limited its scope of reform. Those limitations notwithstanding, the bureau was an import source of support for Georgia’s freedpeople, providing educational opportunity, furnishing rations for the sick and indigent, and ensuring at least some measure of justice and stability at a time when the state and nation were undergoing sweeping change.