The sectional crisis of the 1850s, in which Georgia played a pivotal role, led to the outbreak of the Civil War (1861-65). Southern politicians struggled during the crisis to prevent northern abolitionists from weakening constitutional protections for slavery. During this period, however, and for much of the antebellum era, Georgians maintained a relatively moderate political course, often frustrating the schemes of southern radicals. The passage in 1850 of the Georgia Platform, which endorsed the Compromise of 1850, helped to avert secession for a decade.

The Mexican War and Its Aftermath

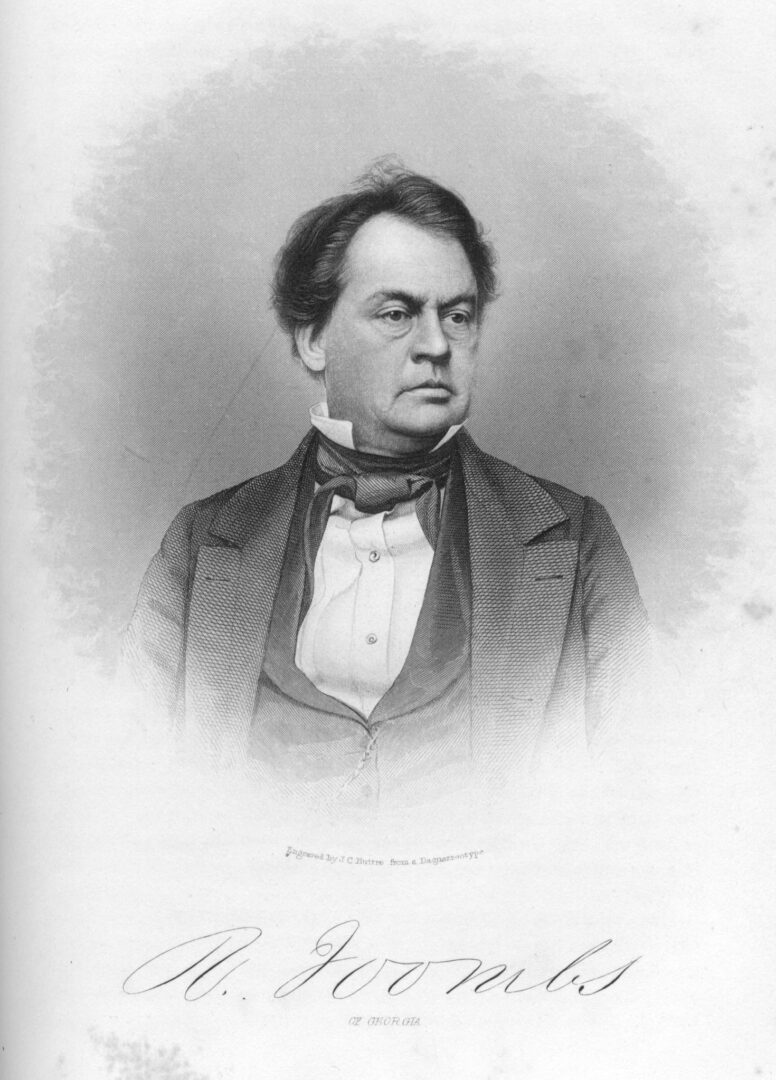

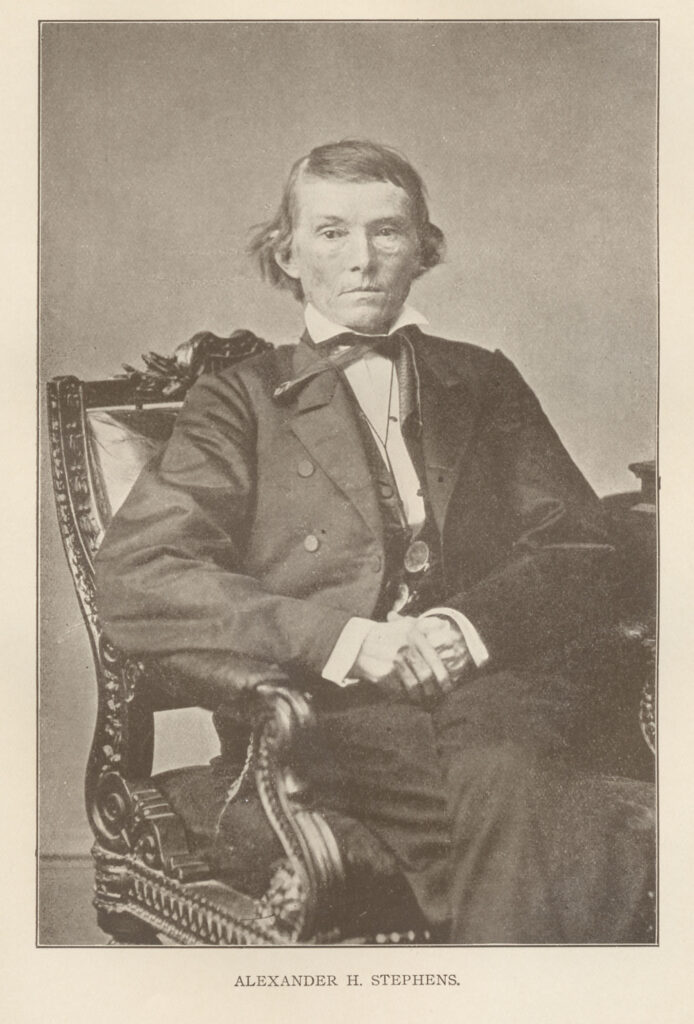

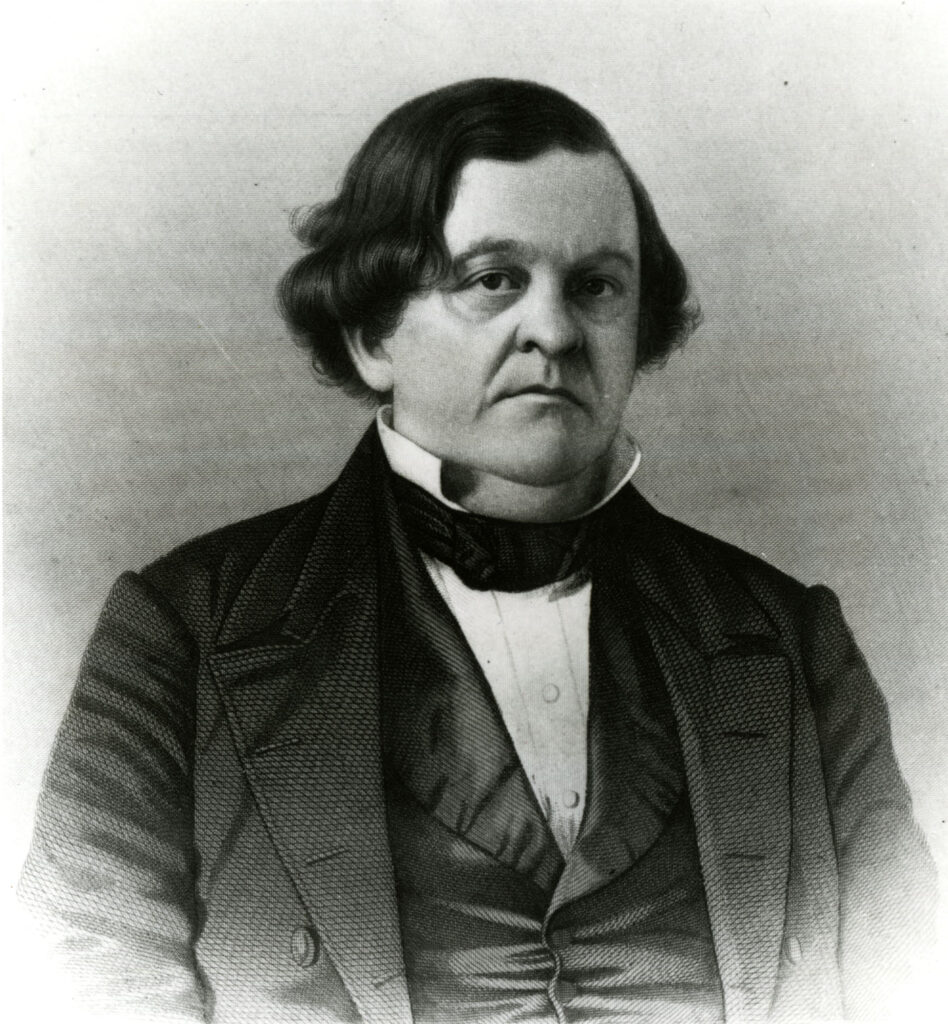

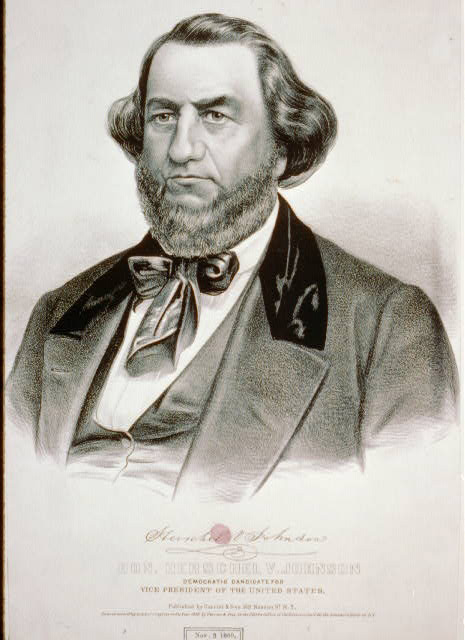

The national debate over slavery intensified in the wake of the Mexican War (1846-48). By 1840 the national Whig and Democratic parties had crystallized in Georgia, creating a strong two-party system that would last in the state for the next decade and a half. The Whigs were led by George W. Crawford, who served as governor from 1843 to 1847, and by rising stars Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs. The Democrats were headed by the equally capable Howell Cobb, Herschel Johnson, and George W. Towns. The two parties remained evenly matched for much of the 1840s, but the Mexican War placed Georgia Whigs in a defensive position from which they never recovered.

Echoing their northern counterparts, Stephens and other Whigs criticized the war for provoking dangerous questions regarding the status of slavery in the western territories, which the United States stood destined to acquire by defeating Mexico. And while it was a Pennsylvania Democrat who in 1846 offered to Congress the so-called Wilmot Proviso, a measure seeking to ban slavery from these newly acquired territories, many more northern Whigs than northern Democrats seemed to favor it. Partially as a result of appearing tied to an antislavery party, Georgia Whigs lost the governorship in 1847 to States’ Rights Democrat George W. Towns. They would never win it back.

As the Whigs predicted, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the Mexican War and bestowing the Mexican Cession (the name given to the territorial package that the United States acquired from Mexico), brought slavery to the forefront of a national debate. Politicians seeking sectional compromise instead of the controversial Wilmot Proviso suggested either popular sovereignty within the territories or an extension to the West Coast of the line established by the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which generally prohibited slavery above latitude 36°30′ north.

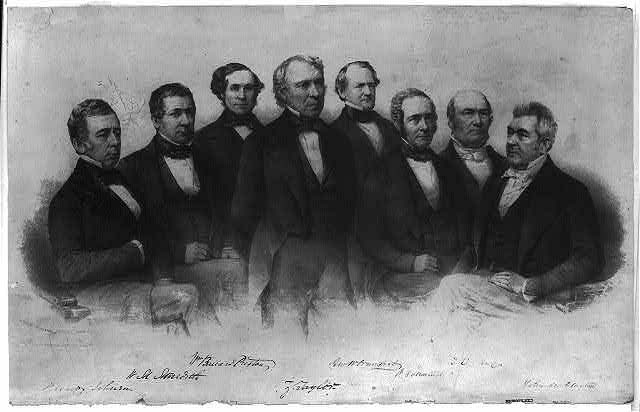

South Carolinian John C. Calhoun and his radical southern followers refused compromise, however, and insisted that the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the legality of slavery in all national territories. Calhoun then called for a politically united South to pressure the federal government into accepting his position on the territories, threatening secession if Congress attempted to prohibit slavery’s westward expansion. Seeking his own course, however, U.S. president Zachary Taylor, a Louisiana Whig elected in 1848, unexpectedly began preparing the Mexican Cession’s California territory for immediate statehood in 1849. California appeared destined to enter the Union as a free state, a development that would upset the sectional balance in the U.S. Senate at the expense of the South. Congress, with Georgia’s Howell Cobb serving as House Speaker, resisted Taylor’s scheme for fear that a free California would provoke southern disunion.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Furious over Taylor’s nationalist agenda, Calhoun’s radicals scheduled a Southern Rights convention to meet in June 1850 at Nashville, Tennessee, where they hoped to rally the region’s political leadership and perhaps begin preparations for secession. Georgia’s politicians broke party lines over the question of joining the Southern Rights movement. Some, like Herschel Johnson and Governor Towns, eagerly jumped on the Southern Rights bandwagon, while many others, including the powerful triumvirate of Cobb, Stephens, and Toombs, rejected the radicals’ call. In stark contrast to their divided political leaders, the vast majority of white Georgians continued to support the Union, and only 2,500 people even bothered to vote in the April election for state delegates to the Nashville convention.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Back in Washington, D.C., Kentucky senator Henry Clay sought to end the sectional controversy over the Mexican Cession by formulating a series of compromise proposals. Under the resulting Compromise of 1850, passed in September with the support of congressmen Cobb, Stephens, and Toombs, California was admitted as a free state while a decision regarding the status of slavery in the Utah and New Mexico territories was indefinitely postponed. Additionally, the slave trade was abolished in Washington, D.C., to satisfy northerners, while a tighter Fugitive Slave Law was designed to appease southerners. Nevertheless, many southern radicals (known as “fire-eaters”) quickly dismissed the Compromise of 1850 for unevenly benefiting the North, and they continued to advocate secession.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Georgia Platform

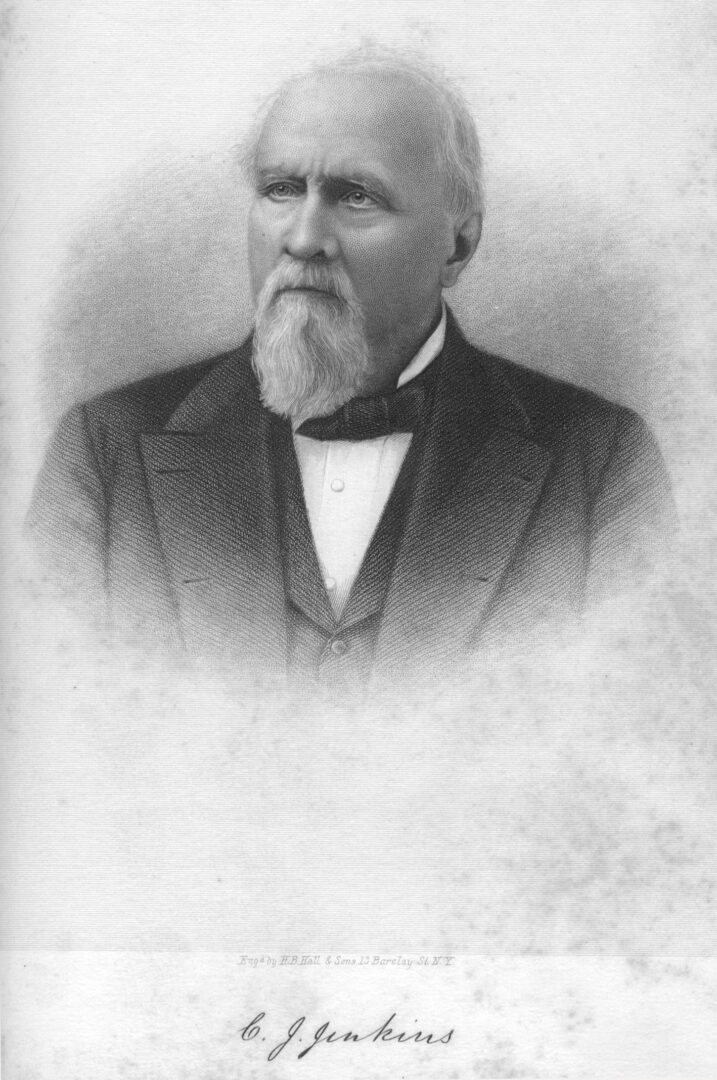

Mistakenly believing that white Georgians supported the radical cause, Governor Towns scheduled elections for a December 1850 state convention in the hopes of launching the state toward secession. But the plan backfired dramatically as Georgia voters elected a resoundingly pro-Union delegation by a convincing 20,000-vote majority. At the December convention, only 19 of the 264 delegates refused to sign the famous Georgia Platform drafted by legislative leader Charles Jones Jenkins. That resolution pledged support for the Union and the Compromise of 1850 under the conditions that the federal government would not try to prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories and would enforce the strengthened Fugitive Slave Act. The result of a strong popular mandate and a document that satisfied the North and the South, the Georgia Platform effectively stifled the radical movement and ended talk of secession. For good measure, in 1851 Georgians elected Unionist Democrat Howell Cobb for governor over States’ Rights candidate Charles McDonald by a decisive 18,500 votes.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

With the national crisis cooling off after the passage of the Georgia Platform, state politicians seemed to settle back into their old partisan camps. Yet for the rest of the decade Georgia Democrats would continue growing in dominance while the Whigs slipped further into decline. In 1852 Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs rejected the Whig Party’s presidential nomination of Virginian Winfield Scott, whose political alliances with antislavery northerners pointed to a repeat of Taylor’s nationalism. Both leaders eventually drifted into the Democratic ranks.

Nevertheless, even after the national Whig Party dissolved in the wake of Scott’s devastating defeat to Democrat Franklin Pierce, Georgia Whigs continued to muster a sizeable anti-Democratic front under a number of different party labels. In 1853 Whig Charles Jones Jenkins ran for governor on a Unionist ticket and nearly upset Democrat Herschel Johnson. The gap widened in 1855 when Garnett Andrews, running under the anti-immigrant American Party label, failed to unseat Johnson despite the fact that less than 2 percent of Georgia’s population was foreign born. The Democrats would keep the governor’s chair for the rest of the 1850s, and the Whig Party’s moderating influence over Georgia politics steadily eroded.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The End of Moderation

Despite its moderate tendencies in the 1840s and 1850s, Georgia remained deeply wedded to the institution of slavery. By 1860 one-third of Georgia’s white families claimed people as property, roughly half the state’s total wealth was invested in slavery, and 462,000 enslaved people made up nearly 44 percent of Georgia’s total population. The rise of the antislavery Republican Party in the mid-1850s therefore pushed white Georgians to abandon their tradition of political moderation.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Starting in 1854 controversies surrounding slavery in the western territories again unleashed a storm of national controversy that this time would culminate in civil war. In a highly miscalculated move, Democratic senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois proposed to organize the territories immediately west of his home state under the doctrine of popular sovereignty, a proposal that violated the cherished 36°30′ line established by the Missouri Compromise. The resulting Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 infuriated many white northerners who feared that Douglas had opened the door for slavery’s westward expansion, which would close off a potential future frontier for white free labor.

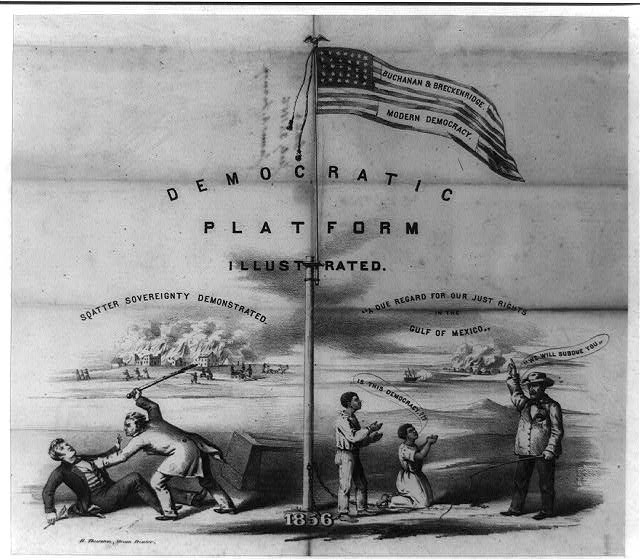

Northern resentment quickly gave rise to the Republican Party, a purely sectional organization intent on banning slavery from the western territories. Proving the party’s electoral strength, Republican presidential candidate John C. Fremont came shockingly close to winning the election in 1856 despite the fact that Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky were the only slaveholding states to place his name on their ballots.

As national politics became increasingly wrought with sectional antagonism, Georgia’s tradition of political moderation disintegrated. State politicians viewed the Republicans as antislavery fanatics seeking to destroy slavery even in the South, and many considered secession a necessary remedy in the event that the Republicans captured the presidency. State politics began to reflect the changing mood. After maneuvering the Democratic nomination away from moderate Howell Cobb, states’ rights advocate Joseph E. Brown handily defeated pro-Union candidate Benjamin Hill in the 1857 gubernatorial election. A self-made businessman and small slaveholder from the north Georgia mountains, Brown crafted a popular Jacksonian political style by denouncing state banks during the 1857 recession, providing increased funding for Georgia’s woeful public schools, and lowering taxes. Riding a wave of popular support, Brown easily won reelection in 1859 by crushing opposition candidate Warren Akin, the last of the neo-Whig challengers. The ardent States’ Rights Democrat would thus occupy the governor’s chair during the greatest political crisis in Georgia history.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The Presidential Election of 1860

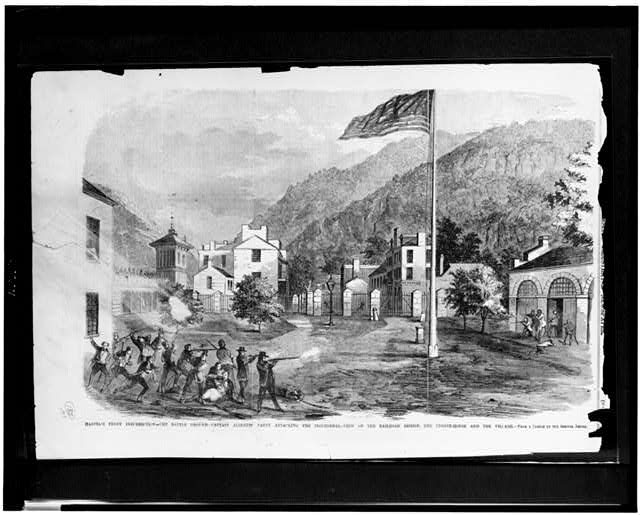

Compounding sectional antagonisms exponentially, abolitionist John Brown was captured leading an attack on a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859. It soon became clear that Brown had planned to use the arsenal to arm a massive slave insurrection. Despite the failure of Brown’s raid and his subsequent execution in December, the incident cast an ominous shadow over preparations for the presidential election of 1860.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

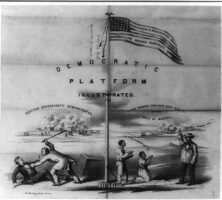

The national Democrats proved incapable of agreeing on a platform position regarding slavery in the territories and sundered along sectional lines. The remaining regular Democrats nominated Stephen Douglas for president (with Georgia’s Herschel Johnson for vice president), while the southern faction selected Kentucky’s John C. Breckinridge, thus dividing the Democratic Party along sectional lines. Soon thereafter a group of Unionist ex-Whigs selected a third presidential candidate in Tennessean John Bell. The Republicans nominated another ex-Whig, Illinois’ Abraham Lincoln, on a platform that reaffirmed the Wilmot Proviso. As with Fremont in 1856, Lincoln’s name did not appear on Georgia ballots.

With Johnson as his running mate, Douglas campaigned personally in Georgia but was rewarded with only 11,500 votes. On the other hand Unionist John Bell captured roughly 43,000 ballots, showing that the old Whig banner still retained some viability in the state. Breckinridge, whose candidacy was largely equated with supporting southern secession, managed to win Georgia with 52,000 votes.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Yet despite Breckinridge’s victory, the combined vote totals of Unionist candidates Douglas and Bell surpassed the Kentuckian’s tally, suggesting that the majority of Georgian voters were not yet ready to forsake the national Union. Lincoln won the presidency by garnering a majority of the Electoral College despite receiving virtually no support from any southern state. Upon learning of Lincoln’s victory, Governor Brown recommended the allocation of $1 million for the state’s defense, which was appropriated by the state legislature, and scheduled January 2 elections for a special state convention to discuss secession. The struggle over Georgia’s future in the Union had begun.