One of the most polarizing figures of the Black freedom movement, H. Rap Brown gained prominence as chairman of the Atlanta-based Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the late 1960s. Brown later converted to Islam and adopted the name Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin.

Hubert Gerold Brown was born on October 4, 1943, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His father, Eddie Charles Brown Sr., worked for Esso Oil, and his mother, Thelma Warren Brown, was a domestic worker and elementary school teacher. From an early age, Hubert Brown excelled at a form of street poetry known as the dozens, and his verbal dexterity earned him the nickname “Rap.”

After a stint as a sociology major at Southern University, Brown moved to Washington, D.C., to join his brother in the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG). NAG was a campus affiliate of SNCC, and most of its members, including future SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael, attended Howard University. By 1965, Brown’s unique ability to organize both college students and community members had earned him the position of NAG chairman. In March of that year, he joined a delegation of civil rights leaders for a White House summit with President Lyndon Johnson regarding voting rights protests in Selma, Alabama, and directly criticized the president for inaction.

In fall 1966 Brown left Washington for Alabama, where he directed SNCC’s voter registration efforts in Greene County. Having worked in Holmes County, Mississippi, during the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign, he knew well the difficulties of registering Black voters in the Deep South. In Alabama, Brown was part of SNCC’s effort to cultivate freedom organizations—independent, county-level Black political parties—through which locals might challenge Democratic control in the region. Despite disappointing results at the polls, Brown impressed SNCC’s leaders and rose to the position of Alabama State Project Director.

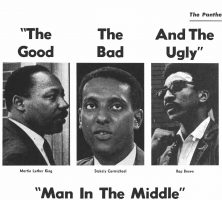

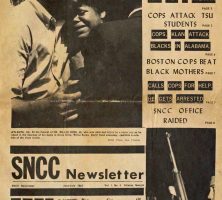

The late 1960s witnessed an important shift in direction for SNCC. With the civil rights movement’s principal legislative goals met, leaders like SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael began to call for Black Power. When Carmichael faced legal trouble in spring 1967, the organization met at Paschal’s Restaurant in Atlanta and selected Brown to take his place. Most hoped that Brown would attract less media attention than had Carmichael. Brown’s goals for SNCC included transforming it into a human rights organization in solidarity with the decolonizing world, opposing the Vietnam War (1964-73), and reinvigorating the freedom organizations that had suffered setbacks in the 1966 elections.

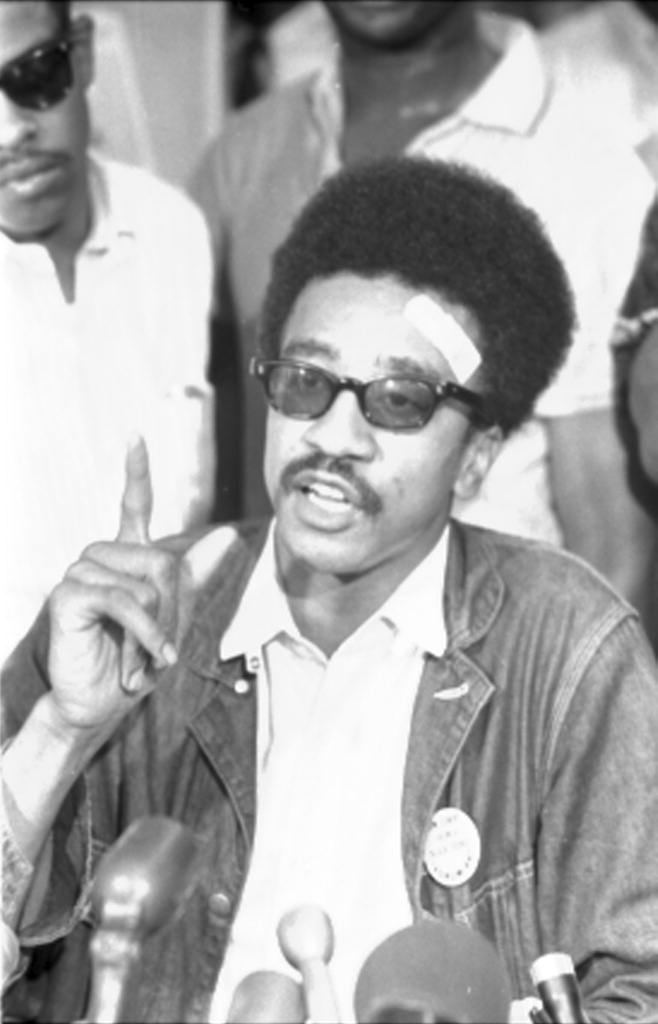

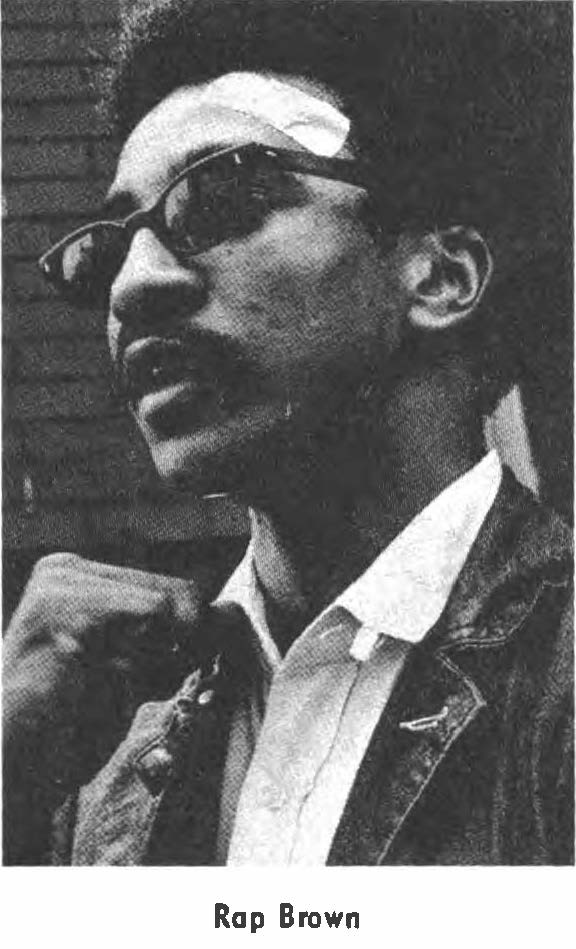

Yet Brown soon proved as provocative as Carmichael. In press conferences and speeches, his frank manner struck many as aggressive. At a time when the Cold War had narrowed the scope of acceptable political discourse, his open support for African socialism and frequent citations of Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong seemed beyond the pale. In a sharp critique of American culture often interpreted as a threat, Brown famously told a press gaggle that violence was as “American as cherry pie.”

Many young people, however, found Brown’s radical message and confrontational style refreshing. He denounced American racism in terms seldom used by more conventional civil rights leaders, and he espoused a revolutionary-nationalist politics that echoed that of the California-based Black Panther Party, of which he would become an honorary officer. Yet SNCC’s organizational effectiveness declined as controversy seemed to follow its charismatic new leader.

On July 24, 1967, at the invitation of veteran civil rights leader Gloria Richardson, Brown delivered a speech in Cambridge, Maryland. From atop a car, he railed against the economic exploitation of Black communities, comparing Black Americans to colonized people around the world. “If this town don’t come around,” he told his audience, “this town should be burned down.” Accounts of what happened next vary widely, but Brown received a non-life-threatening head wound from police buckshot, and fire broke out in the city’s predominantly-Black Second Ward.

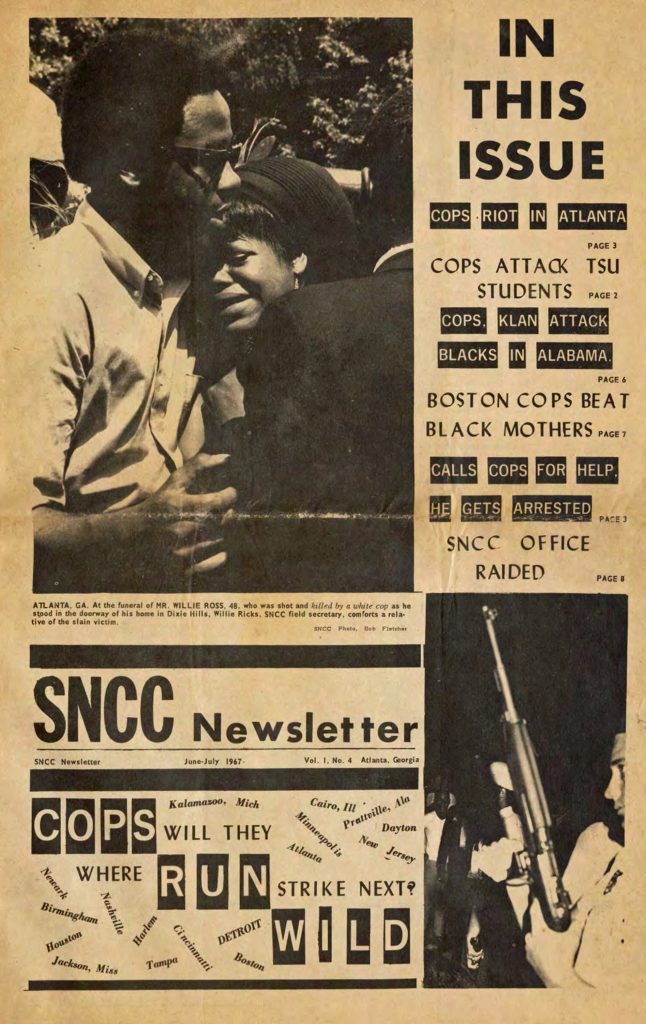

Almost immediately, Brown racked up charges with state and federal authorities for offenses ranging from incitement to riot and advocating criminal syndicalism to interstate transport of firearms while under indictment. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counterintelligence Program (FBI COINTELPRO) had recently stepped up its attempts to neutralize militants like Brown, and the Cambridge incident fueled their pursuit. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover singled out Brown and others in a memorandum calling on field offices to find ways to discredit prominent Black activists. Brown spent much of his chairmanship in and out of jail, and in summer 1968, Phil Hutchings assumed leadership of the nearly-moribund SNCC.

Brown’s 1969 political autobiography, Die Nigger Die!, written in the same provocative style that characterized his stump speeches, drew on the work of revolutionary theorists like Régis Debray and Frantz Fanon. Such manifestoes were a fixture of the late-1960s counterculture, and Brown’s inveighed against what he considered the co-optation of Black Power politics by those less committed to its core principles. It fleshed out his own revolutionary-nationalist politics, the primary tenets of which, by now, were anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism.

Such ideas served as the basis for the short-lived H. Rap Brown Liberation School, a preschool organized in 1969 by the Afro-American Society of Atlanta. Located on Beckwith Street near the city’s historically Black colleges, the school was one of many such independent institutions to appear at the height of the Black Power movement.

In March 1970, Brown was to be tried in Bel Air, Maryland, on charges stemming from the Cambridge incident. When a car bomb killed two SNCC activists in the area, Brown went into hiding. He remained underground until authorities apprehended him in an October 1971 shootout outside a New York bar.

Brown served five years in Attica Correctional Facility on robbery charges connected to the shootout, during which time he converted to Islam and became Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin. He spent the next quarter century as a Muslim faith leader in Atlanta’s West End neighborhood, where he restored a home and opened a small grocery store. Known locally as Imam Jamil, Al-Amin endeared himself to the West End community, playing basketball with local teens and leading efforts to revitalize the neighborhood.

No longer a prominent radical, Al-Amin appeared to have settled into a more tempered activism. But in 2000, a second encounter with law enforcement placed him at the center of another, more deadly, controversy. In 1999 Al-Amin was arrested following a traffic stop in Cobb County. When he failed to appear for a court appearance the following year, two Fulton County sheriff deputies were tasked with serving a warrant for his arrest. A gunfight ensued outside his grocery, and when the smoke cleared, one deputy lay dead, the other wounded. Despite the presence of countervailing evidence, including the account of an eyewitness who testified that he was “absolutely positive” that Al-Amin was not the assailant, Al-Amin was convicted by a representative jury and sentenced to life in prison. On the same day the jury rendered its verdict, a state trial judge ruled that Al-Amin’s original arrest by a Cobb County patrolman had been the result of an unreasonable search and seizure. Al-Amin maintains his innocence, and subsequent appeals have included new exculpatory evidence, including a deposition by federal inmate Otis Jackson, who confessed to the crime.

As an inmate at the Georgia State Prison at Reidsville, Al-Amin assumed the role of faith leader and sought to secure religious privileges for the facility’s small population of Muslim prisoners—activities that aroused concern among prison officials. Though it found no evidence of wrongdoing by Al-Amin, an investigation conducted by Reidsville officials was later cited by the FBI as the basis for his transfer to a federal facility, where he would spend the next seven years in solitary confinement. Supporters claim that Al-Amin’s transfer to federal custody belongs to a pattern of mistreatment by a bureau that surveilled his activities throughout the 1990s, producing a file some 44,000 pages long, but no arrests or indictments. In 2017 a U.S. District Court judge found that prosecutors had violated Al-Amin’s constitutional right not to testify but declined to overturn his conviction, citing the presence of “weighty” evidence against him. When it considered his appeal two years later, a federal appeals court affirmed that prosecutorial misconduct had occurred but determined that it was not likely to have affected the verdict. Al-Amin continues to serve the remainder of his life sentence in federal prison.