Jesse O. Thomas, a protégé of African American educator Booker T. Washington, established in 1919 the Atlanta chapter of the National Urban League, a civil rights organization. During the early twentieth century, he was a pioneer in the upper echelons of national organizations, including some that had been exclusively white until his arrival.

Early Life and Education

Thomas was born on December 21, 1885, in Pike County, Mississippi, to Amanda Johnson and Jefferson Thomas, a church deacon. He attended school in Pike County until the age of fourteen, when his mother died and his family lost the land they had sharecropped for more than twenty years. Thomas took his first job at a sawmill in Natalbany, Louisiana, and it was while working in this industry that he learned of Tuskegee Institute, an African American industrial school in Alabama founded by Booker T. Washington.

Courtesy of Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System

Thomas was an undergraduate at Tuskegee Institute when he caught the attention of Washington, who became the young man’s mentor. His public speaking ability also captivated Tuskegee board members Julius Rosenwald, a philanthropist who funded Rosenwald schools throughout the South, and U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, who urged that Thomas be hired upon graduation to speak for the school. The day after his 1911 graduation, Thomas opened a Tuskegee field office in Rochester, New York. There he became one of the school’s greatest fund raisers, second only to Washington himself.

In the spring of 1916 Thomas left Tuskegee to become the principal of Voorhees Institute (later Voorhees College) in South Carolina. On August 1, 1917, he married Nellie Ida Mitchell, a fellow Tuskegee graduate of Cherokee Indian and African American descent. The year after his wedding, Thomas took a leave of absence from Voorhees to accept two positions in New York City: State Supervisor of Negro Economics and Examiner-in-Charge of the United States Employment Service. In 1919 Thomas resigned from these positions to pursue a degree in social work at the New York School of Social Work. Around this time his only child, Anne Amanda, was born in Texas at the home of her maternal grandparents.

Atlanta Years

In October 1919 Thomas opened the Field Secretary Office of the National Urban League in Atlanta. This marked a significant milestone for the organization, whose southern affiliates had been exclusively white until Thomas’s arrival. Thomas was responsible for hiring the first two Black public school nurses in Atlanta, and in 1920 he organized the school of social work at Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University). His work with the National Urban League sowed the seeds of modern social work in the region.

Atlanta in the 1920s and 1930s attracted many well-to-do African Americans like Thomas and his wife. But this was also the time of racial segregation, and suitable hotel accommodations for African Americans did not exist in the city. Black dignitaries visiting Atlanta often stayed in the Thomas home, a spacious five-bedroom affair in west Atlanta. It was not unusual for Thomas’s daughter, Anne, to awaken to singers Roland Hayes or Paul Robeson playing scales on the family piano. Black intelligentsia, such as Mary McLeod Bethune, William Stanley Braithwaite, W. E. B. Du Bois, and William Pickens, were also guests in the Thomas home.

Thomas organized the 27 Club of Atlanta for top-ranking African American educators to pool their thinking and publish papers. In order to include their wives, the club members hosted formal dinner parties and soirées in their homes. Du Bois and his wife were known to show up for these formal gatherings in street attire—he in a green business suit.

National Prominence

Seventeen years after Thomas brought the National Urban League to Atlanta he was selected for the organization’s Texas Centennial project. In the role of general manager, he battled discrimination during the construction of the Hall of Negro Life, an exhibition for the centennial fair. On July 31, 1936, the Houston Press described the Hall of Negro Life as being in some ways more interesting than similar exhibitions at the fair. Many other newspapers and visitors wrote glowing reports of the hall.

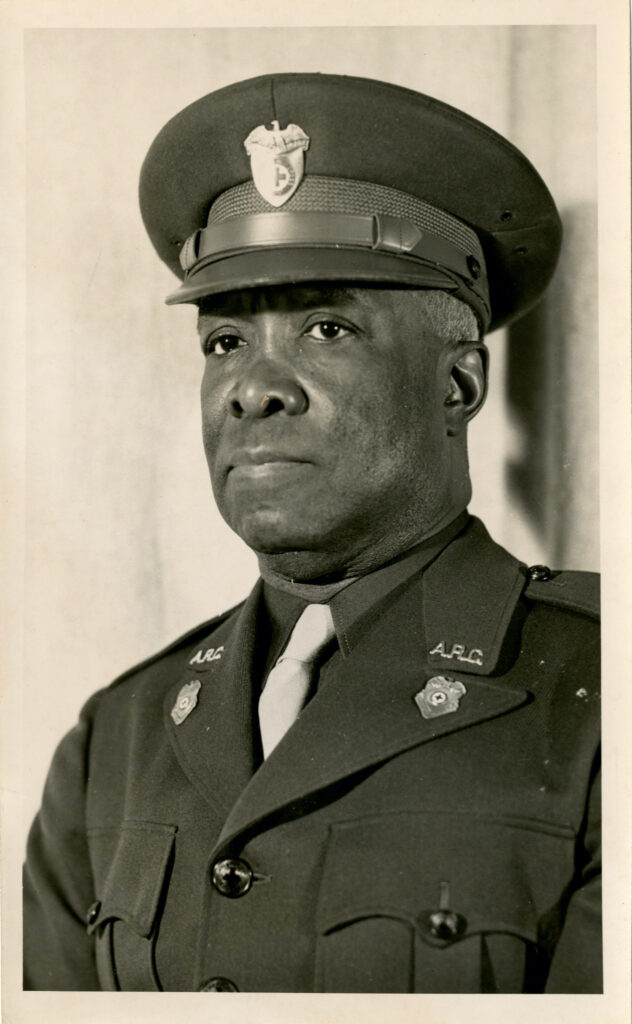

Courtesy of Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System

With World War II (1941-45) looming, Thomas took leave from the National Urban League to craft a program at the U.S. Treasury for selling war bonds in the African American community. His success in this effort led to the American Red Cross recruiting him to join the organization at its headquarters in Washington, D.C. Thomas was the first African American to be hired in any professional capacity with the Red Cross, and it became his job to lead the racial integration of the organization. Thomas left the Red Cross in 1950, at the age of sixty-five, the organization’s mandatory retirement age. He was then recruited to the federal Office of Price Stabilization as one of the staff charged with minimizing inflation in the postwar era.

Later Years

Throughout his career Thomas maintained his primary residence in Atlanta. In the late 1950s he built the Nell-Rose Apartments, named for his granddaughters Nell and Rosemary, next door to his home. But at age eighty, while he was undergoing surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he lost the property. The City of Atlanta seized it and destroyed the buildings for a park.

In 1969 Thomas and his wife moved to Sacramento, California, where their daughter and her husband, John T. Braxton, had worked and retired as vice principals with the Sacramento Unified School District. He was buried there following his death on February 18, 1972.

Thomas’s papers are housed at the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.