From 1868 through the early 1870s the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) functioned as a loosely organized group of political and social terrorists. The Klan’s goals included the political defeat of the Republican Party and the maintenance of absolute white supremacy in response to newly gained civil and political rights by southern Blacks after the Civil War (1861-65). They were more successful in achieving their political goals than they were with their social goals during the Reconstruction era.

Origin

The KKK was formed as a social group in Tennessee in 1866. The name probably came from the Greek word kuklos, meaning “circle.” Klan was an alliterative version of “clan,” thus Ku Klux Klan suggested a circle, or band, of brothers. With the passage of the Military Reconstruction Acts in March 1867, and the prospect of freedmen voting in the South, the Klan became a political organization. Former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest probably served as the Grand Wizard, or overall leader, of the Klan and certainly played a significant role in its organized spread in early 1868.

From The Invisible Empire, by A. W. Tourgee

In Georgia conservative whites, frustrated with their political failures during 1867, began to look for new ways to defeat their Republican enemies and control the recently enfranchised freedpeople. For many, the KKK and its public political wing, the Young Men’s Democratic Clubs, offered a chance to take action. In February and March 1868, General Forrest visited Atlanta from Tennessee several times and met with prominent Georgia conservatives. Forrest probably helped organize a statewide Klan structure during these visits. By the summer of 1868, the Klan was widespread across Georgia.

Organization

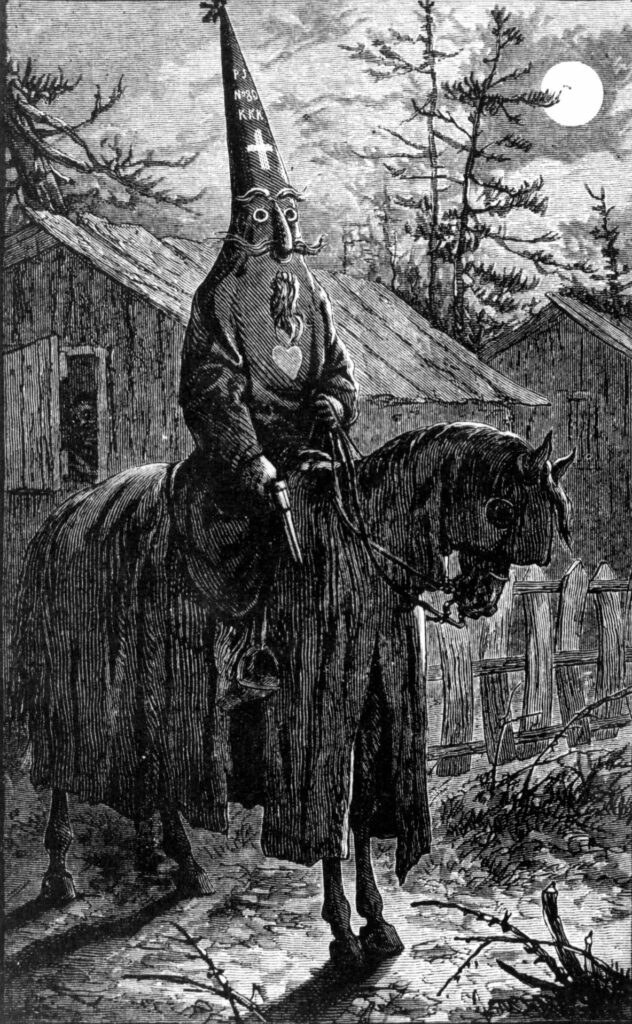

The KKK was a very loosely organized group, and hierarchical structures beyond the county level probably were more symbolic than operational. The Klan in Georgia had a titular head, the Grand Dragon, who at one point was probably General John B. Gordon. Each congressional district had a Grand Titan and under him were Grand Giants for each county. Former Klansman John C. Reed recalled that Robert Toombs’s law partner and son-in-law, Dudley M. DuBose, served as Grand Titan for the Fifth Congressional District while Reed himself served as Grand Giant of Oglethorpe County. In each militia district of his county Reed organized dens of ten or so men, most Confederate veterans with a good horse and a gun. Thus, Reed as a county leader had at his disposal more than 100 armed and mounted men.

The Ku Klux Klan in Action

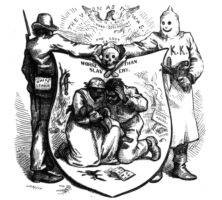

The Klan’s organized terrorism began most notably on March 31, 1868, when Republican organizer George Ashburn was murdered in Columbus, Georgia. Over the following months Klan-inspired violence spread throughout Georgia’s Black Belt and into the northwestern corner of the state. Most Klan action was designed to intimidate Black voters and white supporters of the Republican Party. Klansmen might parade on horseback at night dressed in outlandish costumes, or they might threaten specific Republican leaders with violence. Increasingly during 1868 these actions became violent, ranging from whippings of Black women perceived as insolent to the assassination of Republican leaders. It is impossible to untangle local vigilante violence from political terrorism by the organized Klan, but it is clear that attacks on Blacks became common during 1868. Freedmen’s Bureau agents reported 336 cases of murder or assault with intent to kill on freedmen across the state from January 1 through November 15 of 1868.

From Harper's Weekly

The political terrorism was effective. While Republican gubernatorial candidate Rufus Bullock carried the state in April 1868 elections, by November Democratic presidential candidate Horatio Seymour was in the lead. In some counties the contrast was incredible. In John Reed’s Oglethorpe County, 1,144 people had voted Republican in April, while only 116 dared to vote Republican in November when Reed’s armed Klansmen surrounded the polls. In Columbia County armed Klansmen not only intimidated voters but even cowed federal soldiers sent to guard the polling place. Not surprisingly, while 1,222 votes had been cast in Columbia County for Republican governor Rufus Bullock in April, only one vote was cast for Republican presidential candidate Ulysses Grant in November 1868. Similar political terrorism and control of the polling places help account for Georgia’s quick “redemption” and return to conservative white Democratic control by late 1871.

Klanlike violence was also used to control freedpeople’s social behavior, but with less success. Black churches and schools were burned, teachers were attacked, and freedpeople who refused to show proper deference were beaten and killed. But, Black Georgians fought their attackers, rebuilt their churches and schools, and shot back during attacks on their communities. While these attacks surely terrorized some freedpeople, they failed to destroy the cultural and social independence Blacks had gained with emancipation.

End of the First Ku Klux Klan

There is no clear date for the demise of the first KKK’s activities in Georgia. While John B. Gordon may have left the Klan by late 1868, Klan activity clearly continued throughout 1869 and 1870. After the Klan-supported Democratic triumph in the state elections of 1870, the formal Klan organization began to fade away with aggressive federal intervention in 1871 and 1872. Local Klanlike groups continued to engage in racial and political terrorism, often calling themselves minutemen or rifle clubs, but they lacked larger organizational ties or even commonality of purpose. A romanticized memory of the first KKK legitimated their activities and, combined with the growing power of a Lost Cause mythology, contributed greatly to Georgians’ acceptance of vigilante violence and lynching well into the twentieth century. By the 1890s many men proudly claimed to have ridden with the Klan and thereby saved Georgia and the South from “Negro domination.” This romanticized vision of the Klan was celebrated in popular novels and laid the foundation for the more openly organized Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the second Ku Klux Klan, founded in Atlanta in 1915.