A banker, historian, and civil rights advocate, Malcolm Bell Jr. provided civic leadership to Savannah, produced historical works that make readers think about the nature of the Black experience in the South, and helped to build the Georgia Historical Society into a major force in the study of state history.

Born in Savannah on March 11, 1913, Bell came by his writing and historical talents naturally. His grandfather, Frank Bell, was publisher of the Savannah Morning News; his father, Malcolm Bell, was a staff member of that paper; and his mother, Laura Palmer Bell, was a poet and historian who cofounded the Poetry Society of Georgia in 1923. Bell graduated from Savannah High School and in the early 1930s attended the University of North Carolina, where he was inspired by the progressive ideas of President Frank Porter Graham. He later attended the Graduate School of Banking at Rutgers University, writing a thesis on philanthropy.

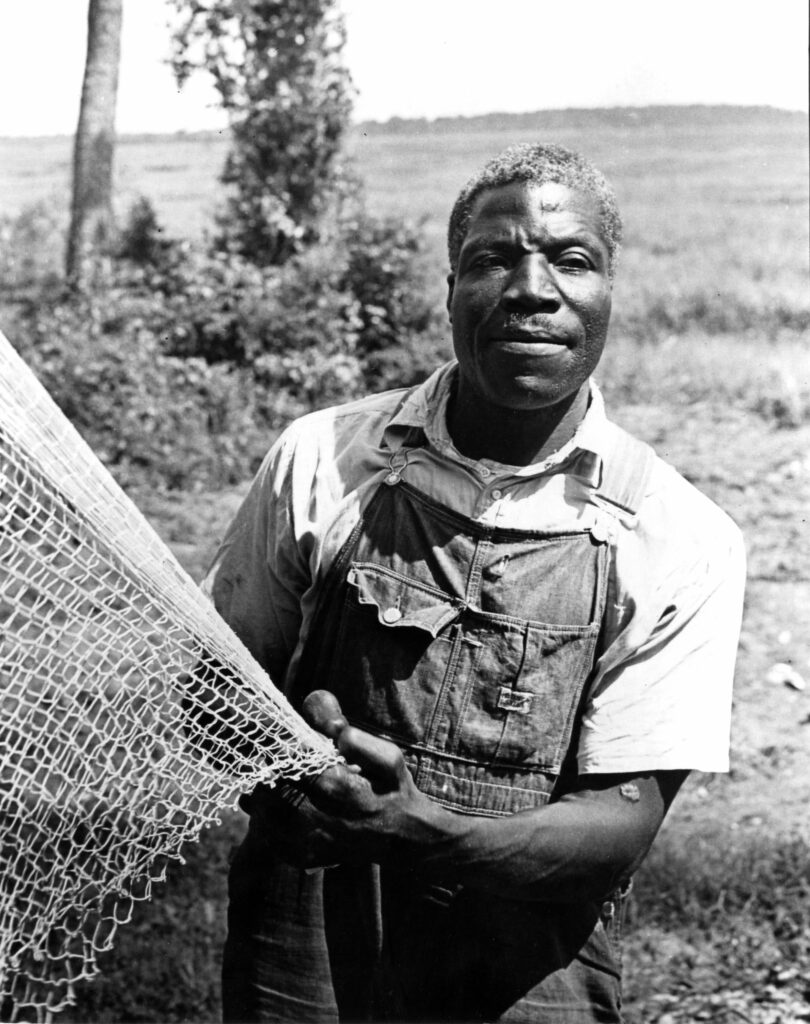

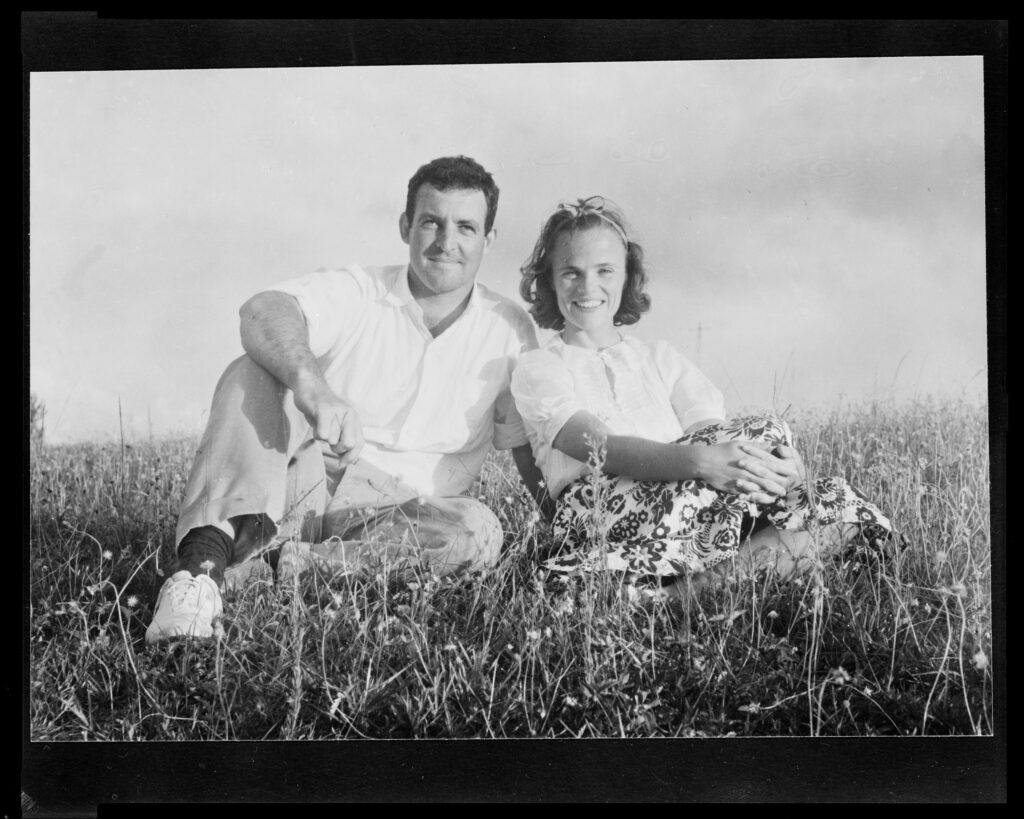

Bell married Muriel Barrow of Savannah, and the couple began preparing for careers as professional photographers. In 1939 the head of the Savannah Unit of the Federal Writers’ Project approached the twenty-six-year-old Bell and his wife to help conduct a study on African survivals in coastal Georgia. The field unit fashioned a pioneering book, Drums and Shadows (1940), termed by sociologist Guy B. Johnson upon its publication as “probably the most thorough search for African heritages among Negroes in a small area that has ever been attempted in this country up to the present time.” The Bells’ photographs are considered classic records of African American culture along the Georgia coast, from Savannah to St. Marys. They composed pictures of carved masks and wooden figures, goatskin-covered log drums and handmade banjos, coil baskets and wooden grave markers, as well as portraits of a simple people marked by dignity and self-respect.

During World War II (1941-45), Bell served in the Coast Guard, entered banking upon his return to Savannah, and became president of the Savannah Bank and Trust Company in 1964. A major force within the life of the city, he served as chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, the United Community Appeal, and the Savannah Port Authority, among other organizations. When race relations reached a critical point in the 1960s, he was one of the few white leaders willing to come forward and listen to concerns in the Black community. The civil rights activist W. W. Law called him a “brave man” for his role in bringing white and Black leaders together.

Throughout these years, Bell became a driving force behind the Georgia Historical Society and the study of Lowcountry history. He served as president of the society from 1974 to 1978, published articles regularly in the Georgia Historical Quarterly , and was an eloquent advocate of its mission on the statewide level. In 1992 the society established in the Bells’ honor the Malcolm and Muriel Barrow Bell Book Award, recognizing annually the best book published on Georgia history.

Bell was passionate about the Black experience in the Lowcountry. After writing Savannah, Ahoy! (1959), an account of the SS Savannah, which in 1819 became the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean, and scripting the text for a pictorial history of the city, Savannah (1977), he focused his attention on the issue of slavery. Bell’s major study, Major Butler’s Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family (1987), grew out of a paper on a sale of enslaved laborers in 1859 in which Pierce Mease Butler, spendthrift grandson of the formidable Major Pierce Butler, sold 436 enslaved people at a location outside of Savannah to settle gambling debts. Bell traces the impact of slavery on the lives of the Butlers: the tyrannical Major Butler and his empire of rice plantations; Pierce Mease Butler, a resident of Philadelphia, and his wife, the English actress Fanny Kemble, who produced an antislavery book; and Owen Wister, the grandson of Butler and Kemble and a writer of westerns.

In 1978 Bell was awarded the Oglethorpe Medal by the Savannah Chamber of Commerce for his many contributions to the civic, cultural, and business life of the community. In 1982 he received the Freedom Fund Award from the Savannah chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for his work with the citizens committee during the 1960s. In 1991 Governor Zell Miller presented Bell with the Governor’s Award in the Humanities.

A modest, unassuming person, Malcolm Bell Jr. earned praise from widely different quarters for his commitment to the African American heritage in Georgia, for the scholarship he produced despite a lack of professional training, and for his role in promoting a forward-looking Savannah at a time when such a phrase could elicit opposition.