W. W. Law was a crusader for justice and the civil rights of African Americans. He served as president of the Savannah chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1950 to 1976 and came to be widely known as “Mr. Civil Rights.”

Born on January 1, 1923, in Savannah, Westley Wallace Law was the only son and the oldest of the three children of Geneva Wallace and Westley Law. He came from a poor family and began working at the age of ten to help his mother after his father died. Later on he credited his success in life to his mother and to Lillie Belle Wallace, his grandmother, who instilled in him a love for reading and social justice. He was also inspired by his mentor, Ralph Mark Gilbert, pastor of the First African Baptist Church, who revived the local branch of the Savannah NAACP; and he admired John S. Delaware, his boyhood scoutmaster, who was a Savannah NAACP official.

In high school, as a member of the NAACP Youth Council, Law protested segregation at Savannah’s Grayson Stadium and worked for the hiring of a Black disc jockey at a white-owned local radio station. Later in college he served as president of the NAACP Youth Council. Law often stated that he would not have received a college degree if Georgia State College (now Savannah State University), where he enrolled in 1942, were not in Savannah. His mother did washing and ironing for white families for very low wages, and there was no money to send Law to college. He worked at the white YMCA in Savannah to finance his education. After completing his freshman year Law was drafted into the army to serve in World War II (1941-45). Upon his discharge the GI Bill paid for the rest of his education at Georgia State College, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology. For many years Law served as the scoutmaster of Troop 49, First Bryan Baptist Church, where he also taught Sunday school. He worked for the U.S. Postal Service as a mail carrier for more than forty years before retiring in the 1990s.

In 1950 Law became president of the Savannah NAACP. In 1962, with the Reverend L. Scott Stell, chair of the NAACP Education Committee, and others, he brought a lawsuit against the segregation of Savannah–Chatham County public schools before the U.S. District Court. U.S. district judge Frank Scarlett held the petition so long that the student plaintiffs graduated from high school. The NAACP then had to refile the case, citing a new group of Black children. Law and the NAACP refiled, and in 1964 the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered public schools in Savannah to be desegregated.

In the 1960s Law began to lead weekly mass meetings at two Savannah churches, Bolton Street Baptist and St. Philip A.M.E., where he advocated passive resistance to segregation. On March 16, 1960, Carolyn Quilloin, a NAACP Youth Council member, was arrested for asking to be served at the Azalea Room lunch counter at Levy’s department store in downtown Savannah. This protest led to others. Law led wade-ins at Tybee Beach and sit-ins at Kress and Woolworth’s lunch counters with NAACP youth workers. He also led an eighteen-month boycott of Broughton Street merchants that forced Savannah’s white leaders to compromise on civil rights.

Law believed that nonviolent means were the best way to open the city for Blacks. He strongly opposed night marches favored by Hosea Williams and his Chatham County Crusade for Voters, believing the night marches allowed people with violent agendas to take to the city’s streets. The Crusade for Voters, headed by Williams, was a separate civil rights organization that was allied with the NAACP. This difference in strategic approach caused a rift between Law’s NAACP and Williams’s Chatham County Crusade for Voters. The rift between Law and Williams prompted Williams and others to leave the NAACP and join forces with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1960 Malcolm Maclean became Savannah’s mayor. Maclean worked with Law and Eugene Gadsden, then the NAACP’s legal counsel, and credited them for keeping violence out of Savannah’s civil rights struggle. Under Maclean, public libraries and store lunch counters were integrated. Signs designating racially separate facilities at city- and county-owned buildings came down.

These triumphs came at considerable personal cost for Law, who was fired from his job at the U.S. Post Office in 1961 because of his civil rights activities. National NAACP leaders and U.S. president John F. Kennedy came to his defense, however, and a three-member appeals board reinstated him.

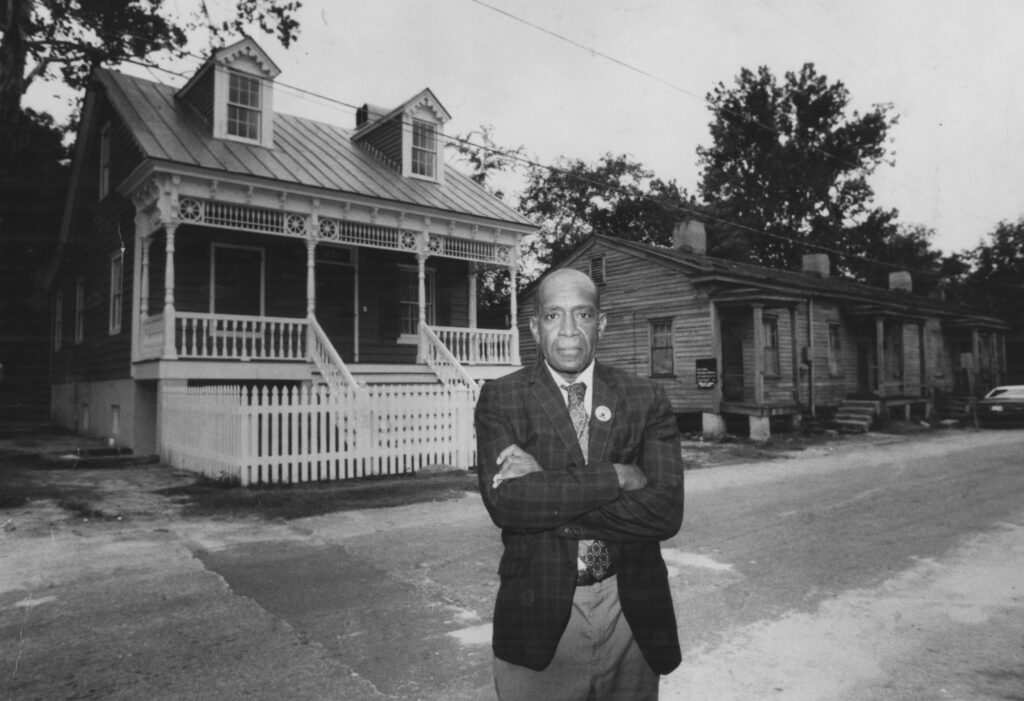

Law retired as Savannah NAACP president in 1976, after serving for twenty-six years. He then turned his attention to the preservation of African American history and historic buildings. He established the Savannah-Yamacraw Branch of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History (ASALH). As president of ASALH, he established the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, Negro Heritage Trail Tour, King-Tisdell Cottage Museum, and the Beach Institute of African American Culture.

Law received honorary doctorates from Savannah College of Art and Design (1997) and Savannah State University (2000), the Distinguished Georgian Award (1998) from the Center for the Study of Georgia History at Augusta State University, the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s National Preservation Award (2001), and the Governor’s Award in the Humanities (1992). Law died on July 28, 2002, at his Savannah home.