Known as Coosaponakeesa among the Creek Indians, Mary Musgrove served as a cultural liaison between colonial Georgia and her Native American community in the mid-eighteenth century. Musgrove took advantage of her biculturalism to protect Creek interests, maintain peace on the frontier, and expand her business as a trader. As Pocahontas was to the Jamestown colony and Sacagawea was to the Lewis and Clark expedition, so was Musgrove to the burgeoning Georgia colony.

Musgrove was the daughter of the English trader Edward Griffin and a Creek Indian mother who was related to Brims and Chigelli, two Creek leaders. She spent most of her childhood straddling the two worlds of her Creek village, Coweta, and the colony of South Carolina. During these years she learned to speak the Creek language of Muskogee as well as English, and she learned firsthand about the deerskin trade and the different customs and expectations of colonial and Native American societies. Despite her mixed heritage Musgrove was considered a full member of Creek society and the Wind Clan. In this matrilineal society, children took the clan identities of their mothers. Later in life she would claim royal heritage, a claim few scholars have accepted.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Businesswoman and Diplomat

In 1717 she married English trader John Musgrove, and together they set up a trading post near the Savannah River. (Archaeologists excavated the site of this trading post in 2002, prior to the beginning of a construction project by the Georgia Ports Authority.) Musgrove helped her husband as an interpreter and probably used her kin ties to attract clients. The establishment of Georgia in 1733 provided the Musgroves an opportunity to expand their role on the southern frontier. In 1734, after John Musgrove and a group of Creeks accompanied James Oglethorpe on a trip to England, the Trustees officially granted John Musgrove some land at Yamacraw Bluff on the Savannah River, four miles upriver from Savannah itself. John Musgrove died in 1735, and Mary Musgrove subsequently moved the trading post to Yamacraw Bluff. The post, known as the Cowpens, became a major commerce site and was probably the center for the English-Indian deerskin trade.

From the colony’s inception Musgrove placed herself in the center of Oglethorpe’s dealings with neighboring Creek Indians. As interpreter for Oglethorpe and Yamacraw Indian chief Tomochichi, Musgrove was instrumental in the peaceful founding of Savannah, and by extension, the Georgia colony. She served as Oglethorpe’s principal interpreter from 1733 until 1743, receiving financial compensation for her assistance and the prestige that accompanied her position. During this period she repeatedly used her connections to foster peace between the British and the Creeks. Oglethorpe obtained most of his understanding of the Creek Indians directly from Musgrove.

Musgrove remarried in 1737. With the assistance of her husband, Jacob Matthews, Musgrove established another trading post at Mount Venture on the Altamaha River. In 1742 Matthews died, and Musgrove remarried once again. Her third and final husband was the Reverend Thomas Bosomworth. This marriage provided an opportunity for Musgrove to further increase her power. The couple probably met when she interpreted for Bosomworth, who was sent to the young colony as a Christian missionary. When the marriage was announced, however, few Georgians believed it to be true. Musgrove’s marriage signified a rise in status that few had foreseen. Musgrove, who had earlier married among the lower branches of the colonial order, now connected herself to “respectable” society. The daughter of an Indian trader and a Creek mother had risen to the upper echelon of colonial society.

Bosomworth’s status and Musgrove’s skills formed a powerful combination. Together they traveled into Creek villages with messages from Oglethorpe and the English king, brought back speeches from various Creek leaders, and hosted Creek and American visitors at their home. They occasionally taught Christian missionaries the Muskogee language, and otherwise tried to mediate interactions between Creeks and colonists.

Controversial Land Claim

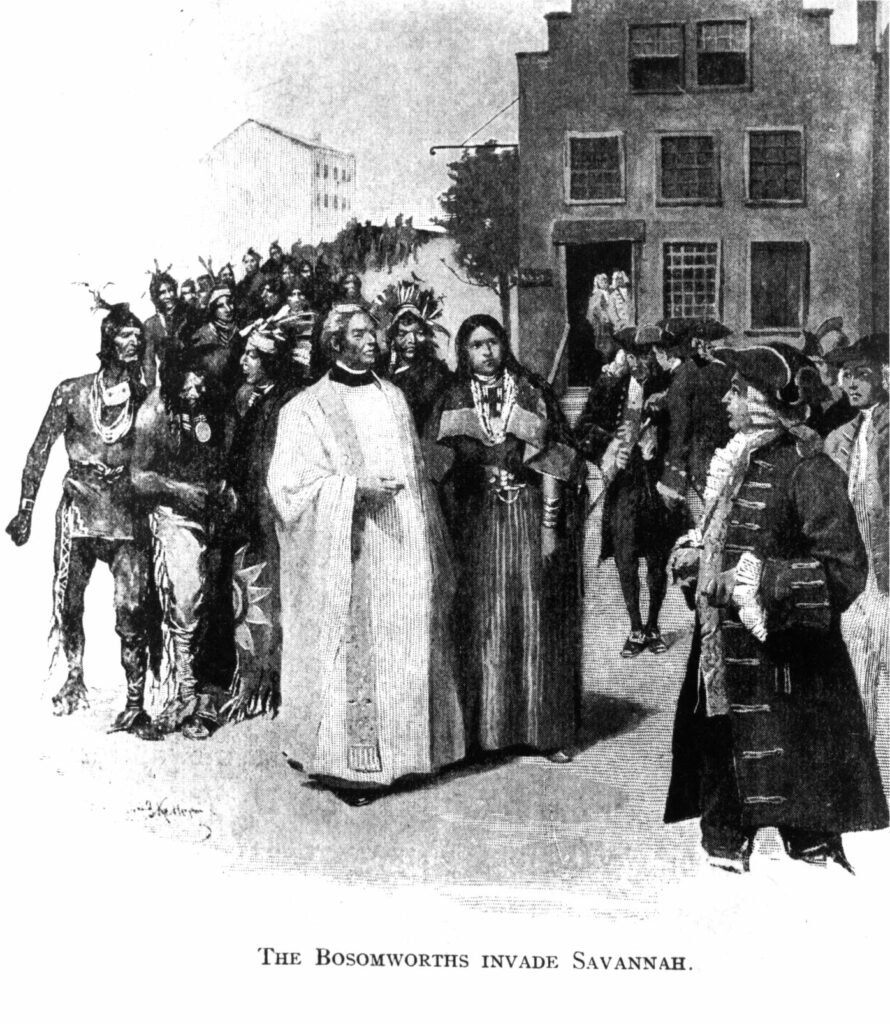

Despite her central role in Georgia’s Indian affairs, Musgrove is more often remembered for her controversial land claims in Georgia. The controversy began in 1737 when Yamacraw chief Tomochichi granted her a plot of land near Savannah. The claim was unsettled when Musgrove married Bosomworth. In the following years Lower Creek chief Malatchi granted the Bosomworths three of the Sea Islands that the Indians claimed as their own—Ossabaw, Sapelo, and St. Catherines. British officials, however, refused these claims on the grounds that a nation can cede or grant land only to a nation, not to individuals.

Musgrove pursued her claims to the lands for the next decade. In 1749 more than 200 Creeks accompanied her to Savannah to support her claim. With Georgia officials unwilling to accept the grant, Musgrove eventually traveled to England to plead her case. In 1754 the Board of Trade heard her case and referred it to the Georgia courts. When she returned to Georgia, the disputed land had come under Georgia control. In 1760 a compromise was finally reached under royal governor Henry Ellis—in return for the right to St. Catherines Island and £2,100, Musgrove relinquished her claims to the other lands. Afterward Musgrove ceased to play a central role in Georgia-Creek relations. She died on St. Catherines Island sometime after 1763.

In 1993 Musgrove was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement.