Paschal’s Restaurant, located in Atlanta’s historic Castleberry Hill neighborhood, was an important meeting place for leaders of the civil rights movement. Founded by brothers James and Robert Paschal, the restaurant and adjacent jazz venue, La Carrousel, were known for serving Black and white patrons in defiance of segregation laws.

Founding and Expansion

In 1947 James and Robert Paschal opened Paschal Brothers Soda, a thirty-seat luncheonette at 837 West Hunter Street. The brothers, originally from Thomson, had backgrounds in hospitality and customer service prior to entering the food service business. Initially, the restaurant only sold cold sandwiches and sodas, but as the shop gained popularity, James and Robert added hot lunches to the menu. The original location had no stove, and neither of the brothers had a car, so the hot food was prepared at Robert’s house and delivered by taxi. In response to the success of the hot lunches, the brothers extended their hours and began serving dinner, including their famous fried chicken, the recipe for which remains a secret to this day. The restaurant enjoyed a brisk business in the years that followed, and by the late 1950s, the brothers were eyeing properties that could accommodate their growing base of loyal customers. As it turned out, they did not need to look far. With an $85,000 loan from Citizens Trust Bank, the restaurant moved to a bigger building across the street. The new location, Paschal’s Restaurant & Coffee Shop, was also the home of the restaurant’s catering service.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

In December of 1960, James and Robert opened a jazz venue, La Carrousel Lounge, adjacent to the restaurant. La Carrousel quickly gained a reputation as “Atlanta’s jazz mecca,” hosting renowned musicians such as Aretha Franklin, Dizzy Gillespie, and Lou Rawls, along with scores of local artists. In segregated Atlanta, La Carrousel Lounge was the only formal nightclub that allowed Black patrons. The club’s clientele was largely interracial, though, despite the fact that the liquor and business licenses specified “colored only.” The jazz lounge pushed the boundaries of segregation and allowed Blacks and whites to mingle socially, which helped establish Paschal’s as the unofficial headquarters of the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

In 1967 Paschal’s underwent its last major expansion with the addition of a six-story, 120-room motel. Paschal’s Motor Hotel was the first Black-owned hotel in Atlanta and employed over 140 people, including students from nearby historically Black colleges and universities. At the height of the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. kept a suite that he used as a planning space.

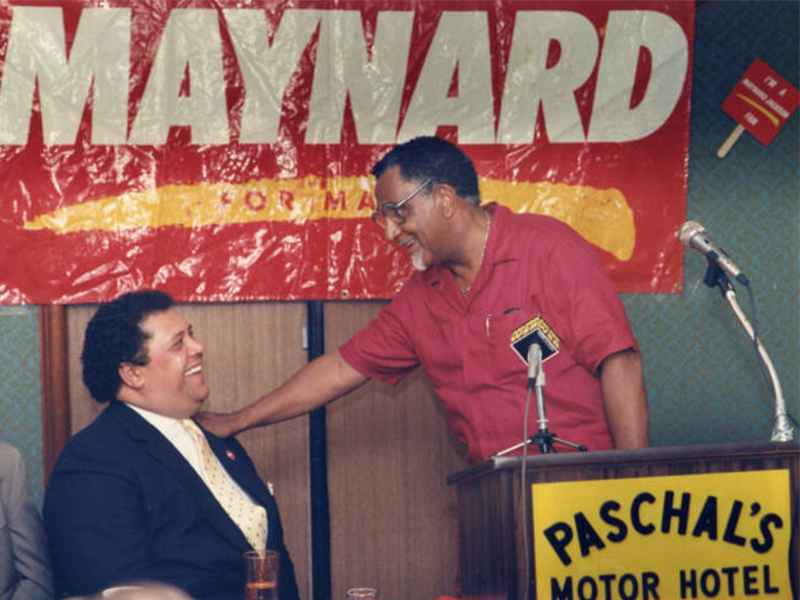

When Atlanta officials announced plans for an expansion of the city’s airport, the brothers sensed yet another opportunity to grow their business. For Maynard Jackson, the city’s first African American mayor, the expansion provided an opportunity to demonstrate the durability of his signature reform effort, a new policy mandating significant minority participation in municipal contracting. Work on the new terminal was completed ahead of schedule and under budget, and when leases for restaurants in the new terminal were made available, the Paschal brothers were prepared to expand once more. In a joint venture with Dobbs Houses Inc., the Paschal brothers won a fifteen-year food and beverage contract at the airport in 1978. That contract was ended in 1993, following a corruption scandal involving William Brooks, president of Dobbs-Paschal Midfield Corp., and city officials. In 1995 Paschal’s was awarded a new contract in partnership with Concessions International, allowing Paschal’s to open a second location at what is now the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Civil Rights Movement

The relationships that James and Robert Paschal built within the city’s Black community made Paschal’s a central meeting spot during the civil rights movement and helped earn the restaurant its reputation as Atlanta’s “Black City Hall.” The restaurant was the meeting space for planning sessions preceding the March on Washington, Poor People’s Campaign, and Mississippi Freedom Summer. Paschal’s also provided a rare space in which Black and white leaders could sit together and talk. Orah Belle Sherman, Paschal’s hostess for over thirty years, purposely sat white and Black patrons together in direct defiance of Atlanta’s segregation laws.

Due to its proximity to the Atlanta University Center—comprised in the 1950s and 1960s of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), Spelman College, Morehouse College, and Morris Brown College—Paschal’s also served as a gathering spot and safe haven for student-led civil rights organizations. Julian Bond, cofounder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), often recalled a day in 1960 when he and seventy-six other student protestors went to Paschal’s for a free meal and to call their parents the morning after being arrested for a sit-in.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Paschal’s remained a hotbed of political activity for Atlanta’s African American community. Maynard Jackson’s campaign team met at Paschal’s to strategize about his first mayoral bid in 1973 and to maintain contact with supporters. Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton made campaign stops at the restaurant, as did legislators Shirley Chisholm and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. To politicians and voters alike, Paschal’s was a mandatory stop to gauge and win the support of the Black community in Atlanta.

Closing and Reopening

In 1996, after years of waning business, Clark Atlanta University bought the restaurant and the brothers relinquished all decision-making rights. In 2002 James Paschal, the only surviving owner, partnered with Atlanta-born businessman Herman J. Russell to open a new location on Northside Drive, still in the Castleberry Hill neighborhood. The original restaurant and Paschal Motor Hotel were renamed The Paschal Center. The restaurant was run as a dining hall, and the hotel operated as a student dormitory and conference center for the next year.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

In 2003, citing high costs for upkeep and little profitability, Clark Atlanta announced it would demolish the original restaurant and hotel, sparking outrage throughout the city. Coretta Scott King wrote an editorial in the Atlanta Daily World urging against the demolition of the historic site. Congressman John Lewis also lent his voice to the efforts to save Paschal’s, noting that the last time he saw Martin Luther King Jr. alive was at the restaurant. In response to the outcry, the buildings were not demolished. However, the original Paschal’s location remains on the Atlanta Preservation Center’s “Most Endangered Historic Places” list.