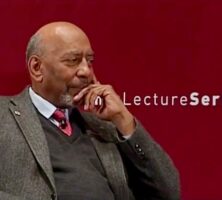

Preston King, an accomplished lecturer and professor of philosophy, lived abroad in exile for nearly forty years. A member of an Albany family well known for civil rights activism, King was convicted of draft evasion in 1961. Believing he had been unfairly treated, he left the country to pursue a career in higher education.

The King Family

Preston Theodore King was born in Albany on March 3, 1936, the youngest of seven sons born to Margaret Slater and Clennon W. King. Civil rights issues were of paramount concern in King’s family. At least three of his brothers, including Albany Movement organizer Slater King, civil rights lawyer C. B. King, and activist Clennon King, were intensely involved in the civil rights movement.

Like his siblings, King excelled in academics, majoring in history as an undergraduate at Fisk University in Nashville, where he graduated magna cum laude in 1956. While a student, King corresponded with the Albany draft board, which addressed him as “Mr. Preston King” in letters, about academic deferments. In 1956, when preparing to study abroad, King visited the draft board’s office, thereby altering the course of his life.

Having discovered that King was African American, the board in all subsequent correspondence addressed him as “Preston” rather than as “Mr. King.” King called the change an intent “to socially disembowel the person,” and “a standard part of operating procedure used to maintain a caste system.” The board, however, did grant King a two-year student exemption, which allowed him to spend the next two years at the London School of Economics and Political Science in London, England. In summer sojourns to the University of Vienna in Austria and the University of Strasbourg and the University of Paris (commonly referred to as the Sorbonne) in France, he studied German and French language and literature.

The Draft versus Graduate School

King’s plan to continue doctoral studies in London necessitated an additional extension of his academic deferment from the Albany draft board. In 1958 the Vietnam era was still several years away, and deferment extensions were routinely being conferred on white men with comparable educational aims. King’s request for a deferment was denied, however.

In 1958, while still in Europe, he received a notice to report for a physical. Because the letter again addressed him as “Preston,” King wrote the board, “I have received government orders with which I cannot in principle comply, due to an immediately conspicuous defect in form. And in the end, I should rather sit in prison, or do whatever else, than submit—an act which I could never square with my conscience—to this reflection of a stupid and insane racialism in government.” He then offered to take the physical if he were addressed as “mister.”

The board nonetheless continued to use the familiar form of address in subsequent letters. King refused to respond to them, which set the stage for federal prosecution. While the resolution of his status was still in question, King returned in 1960 to the United States to give a series of lectures at a dozen colleges along the East Coast. In December federal marshals arrested King during a holiday visit to his family in Albany and charged him with four counts of draft evasion. His father soon secured his release on bail.

At his trial, which took place in Albany in April 1961, King faced an all-white jury. Judge William Bootle from the U.S. Middle District Court of Georgia presided. (In that same year Bootle ruled to end 175 years of segregation at the University of Georgia.) King’s trial lasted for almost a week, and the jury found him guilty on all counts. Bootle, falling in line with the jury’s decision, sentenced King to eighteen months in prison.

With regard to his indictment for evading the draft, King noted that he would have been willing to serve in the military. He also noted that he was tried for disobeying the board, not for refusing to serve. Because he believed an appeal would be futile, given the white power structure in the courts, King jumped bail and left for England. He was subsequently stripped of his U.S. citizenship.

An American in Exile

Once abroad, King enjoyed an extremely successful academic career, completing his Ph.D. at the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1966. Ironically, in his first position, he taught introductory philosophy through the University of Maryland to U.S. airmenat bases in the United Kingdom. From the early 1960s through the mid-1980s, he held positions at the University of Keele in England, the University of Ghana, the University of Sheffield in England, the University of East Africa in Nairobi, the Acton Society Trust in London, the University of Nairobi in Kenya, and the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. In Nairobi and Sydney he held chairs.

Beginning in 1986 he taught in England, first at Lancaster University and then at the University of East Anglia. King has toured and lectured as a visiting professor in Cameroon, Canada, Fiji, Ghana, India, Italy, Tanzania, and Uganda. He has written sixteen books and more than eighty articles and reviews on political philosophy.

Cause Célèbre

King was not allowed to return to the United States for the funerals of his parents or of his brother Slater. As the years passed, unsuccessful pleas to allow King into the country were made by the Georgia House of Representatives, civil rights advocates, Fisk University, the Reform Jewish Movement (whose leadership was also active with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), colleagues, former professors, his daughter Oona King (elected as a Member of Parliament in 1997), and other family members. When his older brother, Clennon, died in February 2000, efforts to bring King back to Albany finally prevailed. At the instigation of his nephew Clennon King, Albany Herald newspaper reporter Tim Wesselman contacted Bootle, who was then ninety-six years old. Bootle reflected, “I suppose he felt that he just couldn’t fight for a country that treated him as a second-class citizen. It’s a pathetic case. He was so obviously discriminated against. . . . It never would have happened to him had he been white.” Bootle’s written plea in support of a presidential pardon significantly aided the effort.

Despite Bootle’s support, King’s pardon request presented a challenge. Although U.S. president Jimmy Carter declared a blanket amnesty in 1977 for those who had not complied with their draft boards’ injunctions, these offenders were not under federal charges, nor had they jumped bail as King had. If an offender had jumped bail, he would need to submit first to the custody of the federal marshals. There was virtually no precedent in recent history, however, for the pardon of a convicted person who had left the country and who was not in federal custody.

The pressure from so many groups and individuals, including Bootle, along with the poignancy of potentially missing another family funeral worked in King’s favor. On February 21, 2000, U.S. president Bill Clinton issued a pardon for King that allowed him to return home after thirty-nine years abroad. The media and hundreds of well-wishers met him for a celebration in Albany’s Veteran’s Park Amphitheater, and Bootle hosted a luncheon at his Macon home for King and his family.

Actively involved in academic circles in the United States and abroad, King lives in Atlanta, where he is affiliated with both Morehouse College and Emory University. He serves as scholar-in-residence at the Leadership Center at Morehouse. At Emory, where he serves as distinguished professor of political philosophy, he edits Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, which he founded. King continues to be a prolific and highly respected political philosopher.