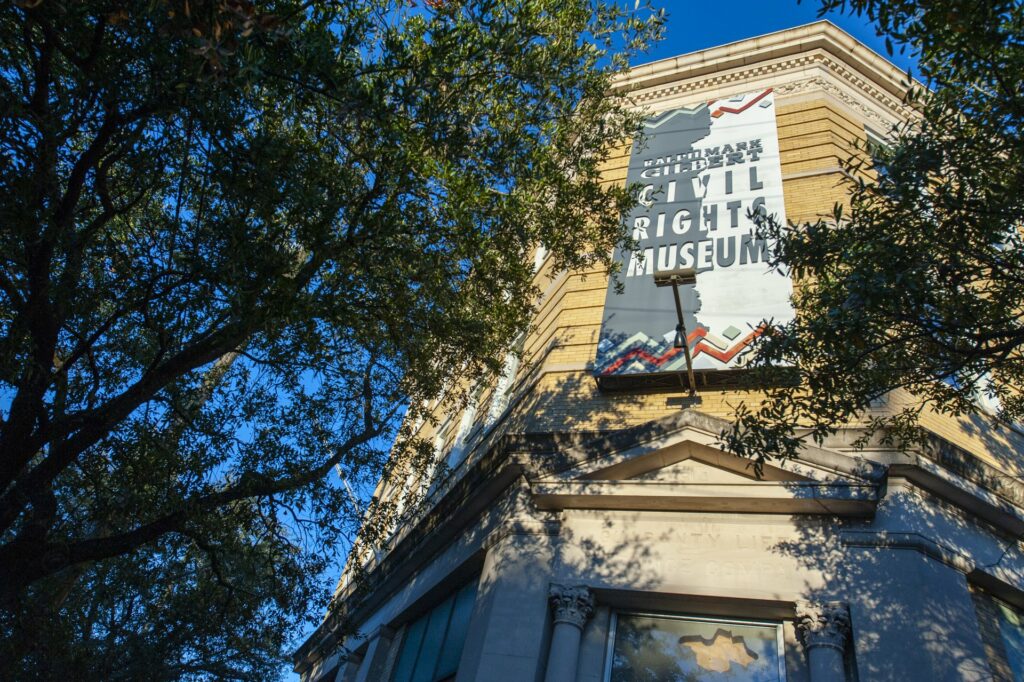

Savannah’s modern civil rights movement was charted by local African Americans and adhered to the principles of nonviolent protest. The Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum is named in honor of the father of that movement. The museum site was originally constructed in 1914 as an African American bank, with Lucius Williams as president. Robert Pharrow, an African American contractor from Atlanta, built the structure. It later served as the Guaranty Insurance Company, with Walter Sanford Scott, a local Black millionaire, as president, and as the Savannah office of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

Gilbert came to Savannah as pastor of the historic First African Baptist Church on Franklin Square, which he served from 1939 to 1956. A graduate of the University of Michigan, Gilbert was nationally known as an orator, tenor, and religious playwright. Gilbert, with members of neighboring churches and the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, organized Savannah’s Greenbrier Children’s Center. In the late 1940s, with financial help from twenty-four people, both Blacks and whites, he also developed the West Broad Street YMCA in the McKelvey-Powell Building, which had served as a USO facility during World War II (1941-45).

Photograph by Carl Elmore. Courtesy of Savannah Morning News

Gilbert reorganized the Savannah branch of the NAACP and was its president from 1942 to 1950. He was the organizer, convener, and first president of the Georgia Conference of the NAACP. Under his leadership, more than forty NAACP chapters were organized by 1950 in Georgia.

Gilbert served as president of the Citizens Democratic Club and challenged the Georgia all-white primary in Savannah by launching a citywide Black voter registration drive, in which hundreds of Blacks were registered. This bold move led to the election of a reform-minded white mayor and city council. As a result, in 1947 Savannah became one of the first cities in the South to hire Black policemen, along with several other Black city employees.

W. W. Law, who became president of the Savannah NAACP in 1950, almost single-handedly led a movement to secure funds for a museum to commemorate Savannah’s civil rights struggle. In 1993 he sought $1 million in funding from Chatham County’s one-cent special local-option sales tax to build the museum. He chose the old Wage Earners Savings and Loan Bank on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard (formerly West Broad Street) as the museum’s site. West Broad Street was the hub of Black businesses, medical doctors, mortuaries, various other professionals, jazz music, and other entertainment. The bank was also near the Bolton Street Baptist Church, where the first civil rights mass meetings were held in the late 1950s and into the 1960s. As a historic preservationist, Law envisioned the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum as a catalyst for reviving the economic and cultural vitality of old West Broad Street.

The Savannah Yamacraw Chapter of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (a nonprofit organization), with Law as president, assumed operation of the museum in 1993. Elorie S. Gilbert, Ralph Mark Gilbert’s widow, donated his letters and papers to the museum.

The museum chronicles the civil rights struggle of Georgia’s oldest African American community. The three floors feature historic photographic and interactive exhibits, including an NAACP organizational exhibit and a fiber-optic map of eighty-seven significant civil rights sites and events. A bronze bust of Gilbert highlights the exhibits on the museum’s first floor, which also features a recreation of the Azalea Room of Levy’s Department Store, where Blacks could buy clothing but could not eat in the restaurant. The mezzanine houses a theater, which is a facsimile of an African American church sanctuary, where Law and other leaders reflect on Savannah’s civil rights struggle. A visual montage of West Broad Street’s people and its commerce gives visitors a glimpse of its history. The second floor features lecture halls, classrooms, and a computer room. It also has a video/reading room and an African American book collection for children.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

The vision of Law and Gilbert came to fruition in the museum. Thousands of visitors from around the world tour the museum, where people of all races can share a glimpse of the struggle for African American civil rights.