Streets named after the civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. are common and controversial landscape features. Although one finds these streets in towns and cities across the country, they are most prevalent in Georgia. This is not surprising, given that so many civil rights organizations, campaigns, and leaders—including King himself—originated in the state.

Black activists frequently encounter controversy when attempting to name or rename streets after King. These controversies expose continuing divisions between Blacks and whites as well as social tensions within the African American community. Location plays a central role in many of these struggles. Community leaders debate which street is most appropriate to identify with King’s memory and whether that street should cut through prominent business districts and unite white and Black communities.

Geography of Martin Luther King Jr. Streets

Naming streets for King is part of a national movement to strengthen public recognition of the historical achievements of African Americans. By 2003 more than 600 cities in the United States had attached King’s name to a street. Of the fifty states, only eleven had no street named after the civil rights leader. More than three-quarters of the nation’s Martin Luther King Jr. streets are located in six southern states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Georgia led the country, with seventy-five as of 2001. King’s name adorns roads in Georgia towns from Adairsville to Zebulon and in all parts of the state. One can find Martin Luther King Jr. streets in such major metropolitan areas as Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon, and Savannah, as well as in small towns including Ailey, Harrison, Irwinton, and Tennille. In fact, 60 percent of all Georgia streets named after King are in towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants.

A strong relationship exists between the likelihood of a city’s identifying a street with King and the relative size of its African American population. On average, Black Georgians constitute approximately 47 percent of the population in a location with a street named for King. In more than 90 percent of places in the state with a Martin Luther King Jr. Street, the Black community makes up at least 20 percent of the population. This pattern is consistent with that in other states and predictable given the role of Black activists in initiating the street-naming process. Indeed, local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization that King once led, have conducted several street-naming campaigns, as have various other Black-led community improvement associations and coalitions.

Symbolic Importance

Few scholars have examined the symbolic importance of the naming of streets after Martin Luther King Jr. When analyzing the commemoration of King, academicians have focused on museums and memorials, such as the national historic site in Atlanta, or on the designation of the civil rights leader’s birthday as an official holiday. In some cities, for example, Atlanta, Columbus, Douglas, Sandersville, and Tifton, streets were renamed for King as early as the 1970s. However, the vast majority of Martin Luther King Jr. streets in Georgia did not appear until after the creation of the King national holiday in the mid-1980s. In Rome and Commerce, local holiday celebration commissions organized street-naming campaigns.

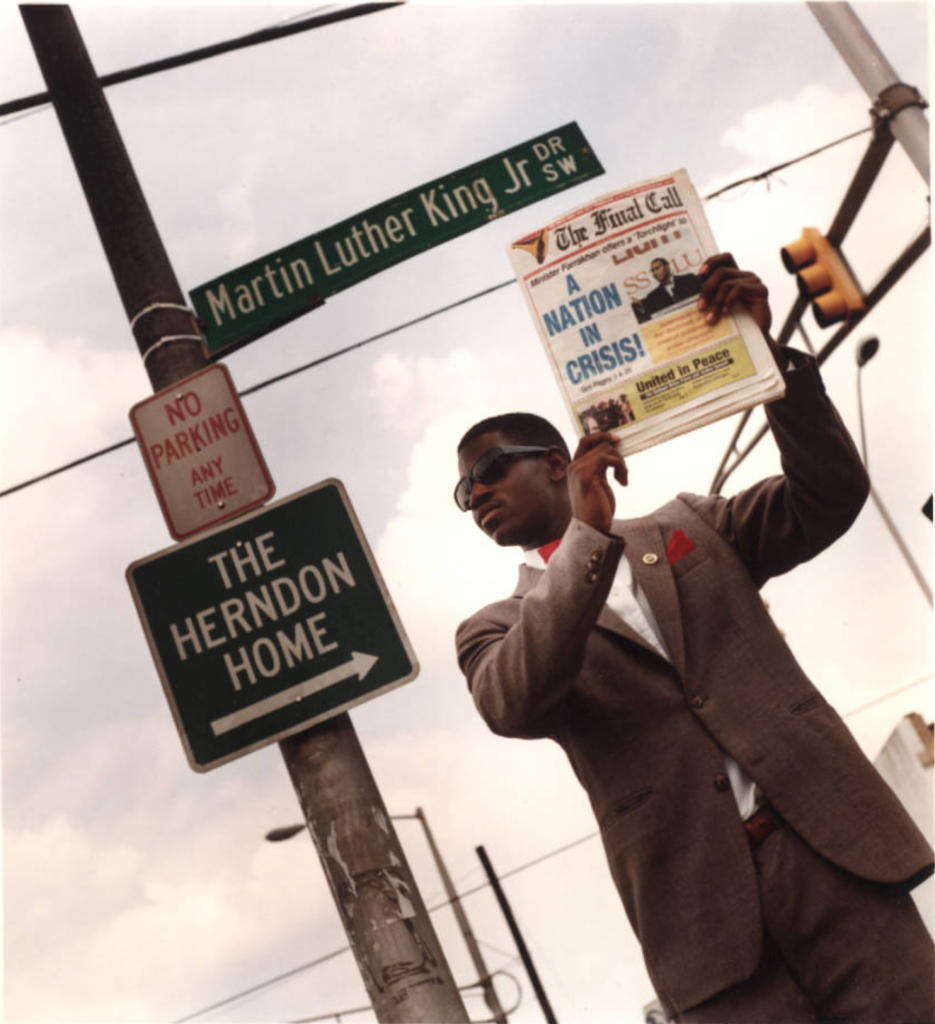

Despite the close association between naming streets and holiday activities, the two commemorative activities differ in terms of symbolism. Commemorative street names, unlike annual holidays, provide a geographic permanence that endures throughout the year. Because of its practical importance, street naming inscribes symbolic messages about the past into much of daily life through road maps, phone book listings, the sending and receiving of mail, advertising billboards, and road signs. It is a street’s potential to touch and connect different social groups that makes naming a powerful and controversial commemorative practice.

The church often plays an important political and symbolic role in the street-naming process, as it does in Black southern culture in general. Indeed, the church is the nonresidential establishment most frequently found on streets named for King. In the town of Metter, in Candler County, a local Black pastor led the movement to rename a street for King. The unveiling of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard took place on the Sunday before the 1996 King holiday, and the dedication service began and ended with prayer and the singing of church hymns. Those attending the service read a litany of dedication, pledging themselves to the ideals of peace, freedom, and equality.

African Americans sometimes differ with one another about the relative meaning and importance of identifying streets with the civil rights leader. For many Black Georgians, however, these streets represent important conduits for political and cultural expression.

The symbolic meaning of streets named for King also depends upon where they are located with respect to memorials to other noteworthy Georgians. In Macon, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard runs near a bridge named for the African American blues artist Otis Redding. King’s street in Eatonton parallels one named after the prize-winning author Alice Walker. In Savannah the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum is located on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, creating a connection between national and local civil rights leaders.

The Politics of Street Naming

Although African American activists may view street naming as an important symbolic practice, not everyone identifies with King’s commemoration in the same way. Consequently, streets named for King are often sites of social struggle. Naming a street in Americus proved particularly controversial. City officials did not rename a portion of U.S. 19 until Black community leaders planned a boycott of city businesses. Part of the controversy stemmed from the comments of a white fire official who said he would support naming half of the street for King if authorities named the other half for James Earl Ray, the man convicted of assassinating the civil rights leader.

The politics of street naming concerns not simply the appropriateness of commemorating Martin Luther King Jr. but also where best to locate or place his memory within the cultural landscape. The city of Cartersville renamed Moon Street for King only after a series of petitions, counterpetitions, and debates over alternative streets. In Sylvester two Black city council members voted against a street-naming proposal when they learned that King’s name would be placed on a road that dead-ended into a poor, deteriorating neighborhood. African Americans living on Reese Street in Athens opposed identifying their street, which they described as “unknown” and “drug-infested,” with a great historical figure.

When African American activists seek to remember King on prominent thoroughfares, they often encounter harsh opposition from owners and operators of businesses along the street. Businesses cite the financial burden of changing their address and the symbolic cost of being associated with the Black community. For instance, a petition drive organized by business owners in Statesboro blocked a proposal in 1997 to rename a major commercial artery for the civil rights leader. Women activists in Gainesville finally persuaded their city council to rename Myrtle Street in 2000. The group unsuccessfully had made this request three times before; the fourth time, under pressure from business and property owners along the street, the group adjusted their original proposal and requested the renaming of only a portion of the road.

Even in King’s hometown of Atlanta, commercial interests opposed the naming of a street in his honor, though without success. Today, Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, on the west side of the city, is the location of significant development and a major landmark in the city’s tourism industry. In Georgia as a whole, however, 2.3 times as many residences as nonresidential establishments have Martin Luther King Jr. addresses. This figure is well below the national average for King streets but consistent with the norm for the South.

In choosing where to commemorate King, African Americans are often sensitive to the racial composition of the street. They often seek streets that reach beyond the geographic boundaries of the Black community. In their eyes it is important for people of all races to honor King. The friction over where to commemorate King is not just between Blacks and whites, however. In 1995 African Americans in Carrollton collided over the issue. The city honored a convenient request by the First Baptist Church to rename King Street, originally named after a local plantation owner, for Martin Luther King Jr.

King Street was composed largely of African American residences. Leaders of the local NAACP chapter opposed the church’s proposal, preferring to rename Alabama Street, a busy commercial thoroughfare, for King. Eatonton saw a similar difference of opinion between African American leaders—one lobbied for the naming of a highly visible bypass; the other persuaded government officials to rename a main residential artery in a Black neighborhood. According to 1990 census data for Georgia, African Americans made up 79 percent of the population in census tracts containing a street named for King. Ninety-seven percent of census tracts with a named street had a higher proportion of Blacks than the total population of the city in which the street was located.

Streets named for Martin Luther King Jr. are important symbols. Like the civil rights movement they commemorate, these streets symbolize both Black empowerment and struggle. They provide windows into not only the historical importance of King but also society’s relative progress in fulfilling the civil rights leader’s “dream” of racial equality and social integration.