Rosa Lee Ingram was an African American woman whose 1948 murder conviction, along with the conviction of two of her adolescent sons, raised considerable doubt about the integrity of Georgia’s judicial system. Civil rights organizations launched an ambitious campaign to free the Ingrams in the years that followed. As a result of these efforts, Ingram and her sons were paroled in 1959.

Death of John Stratford

Rosa Lee Ingram was a widowed sharecropper and mother of twelve who lived near Ellaville, Georgia. On November 4, 1947, a confrontation broke out between Ingram and her neighbor, John Ethron Stratford, after he discovered some of her livestock in his field. According to Ingram’s initial account of the incident, Stratford threatened her with a rifle. Several of her sons intervened, a fight ensued, and when the dust settled, Stratford was dead.

Ingram was arrested along with three of her teenage sons: seventeen-year-old Charles, sixteen-year-old Wallace, and fourteen-year-old Sammie Lee. The four were placed in separate jails and were not provided legal counsel. Local authorities would later claim that Rosa Lee, Wallace, and Sammie Lee revised their initial account of the altercation while in custody. According to these new statements, two struggles occurred, and Stratford was killed during the second one, when the Ingrams seized his rifle and pursued him as he ran to his house. Charles, however, refused to change his statement, insisting that only one confrontation had occurred.

Photograph from BlackPast.org

The Trial

Rosa Lee, Wallace, and Sammie Lee were tried on January 26, 1948, in Ellaville by Judge W. M. Harper. Charles was tried the following afternoon. Both trials lasted only a single day. Not until the day before the first of the two trials, when S. Hawkins Dykes was appointed as the Ingrams’ attorney, would any of the four defendants have access to legal counsel. Based on his account of their later statements, Sherriff J. E. De Vane informed the jury that the Ingrams followed the fleeing Stratford and beat him to death with several farming tools.

When she took the stand, Mrs. Ingram denied making any such statement. She said that Stratford threatened her with a knife and struck her with a rifle. She then managed to take possession of the gun and struck Stratford about the head in self-defense. She testified that Wallace also struck Stratford once with the rifle, but that none of her other sons had done the same. Wallace and Sammie Lee gave similar accounts on the stand. There were no other eyewitnesses.

Judge Harper told the all-white, all-male jury that the defendants could be found guilty or innocent of either manslaughter or murder. The jury found all three guilty of murder, and Harper sentenced them to death. The next day Charles was acquitted due to insufficient evidence.

Protest of Death Sentence

The conviction was immediately protested by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), and Georgia-based groups such as the Georgia Defense Committee. The Pittsburgh Courier, an influential Black newspaper, brought national attention to the case by running several front-page pieces about the Ingrams. The case also received significant attention from communist publications such as the Daily Worker. A majority of these stories portrayed Mrs. Ingram as a mother protecting her family from a white attacker, making her the face of the family’s campaign for exoneration. The case marked the first occasion that the CRC, a relatively new organization, launched a national campaign to free a Black defendant. The group never represented the Ingrams in court and at times disagreed with the NAACP’s strategy, but it played a significant role in bringing public opinion to the Ingram family’s side.

Image by the National Committee to Free the Ingram Family, Wikimedia

The NAACP joined with Dykes, the Ingrams’ defense attorney, to appeal the conviction. A hearing to decide if they should receive a new trial was held on March 25, 1948. Dykes emphasized the fact that the Ingrams had not received legal counsel until the day before their trial, had been jailed separately, and had possibly been coerced into giving statements to the police. He argued that the most they should have been convicted of was manslaughter. Judge Harper commuted the death sentences to life imprisonment but denied the Ingrams a new trial.

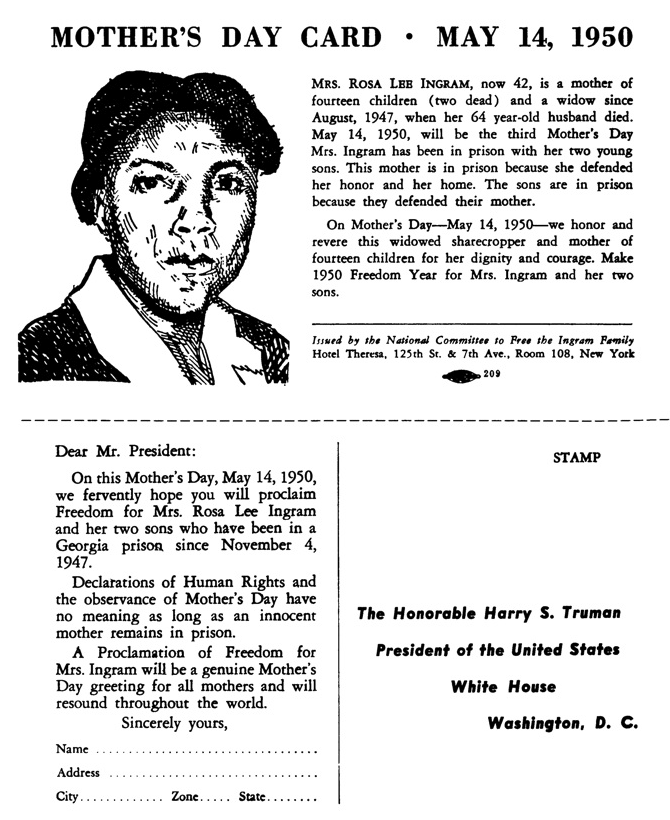

The NAACP and the CRC continued their efforts to free Mrs. Ingram and her sons and sponsored a fund-raising campaign and clothing collection for the rest of the Ingram family. Enough money was eventually raised to build the family a new house. Charles Ingram toured several cities to raise money for the defense of his mother and brothers. The NAACP brought the case before the Georgia Supreme Court, but the court upheld the convictions in July 1948. In March 1949 the all-woman National Committee to Free the Ingram Family (later the Women’s Committee for Equal Justice) was founded by CRC members to promote public interest in the case. Efforts included presenting petitions to President Harry Truman, organizing Mother’s Day rallies, and circulating postcards, clearly putting Rosa Lee front and center in their appeals.

Photograph by Norma Holt, from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library

At the same time, the NAACP had been working behind the scenes in Atlanta to increase the chances of the Ingrams gaining early parole. Several parole requests during the 1950s were denied. In 1957 Georgia officials expressed their willingness to parole the Ingrams, but it took another two years for the board to vote in favor of release. Rosa Lee, Wallace, and Sammie Lee Ingram were released from prison on August 26, 1959. Mrs. Ingram lived in Atlanta until her death in 1980.