Atlanta is the capital of Georgia, the state’s largest city, and the seat of Fulton County.

According to the 2020 U.S. census, the population of Atlanta is 498,715, although the metropolitan area (comprising twenty-eight counties and more than 6,000 square miles) has a population of more than 6 million. It is also one of the most important commercial, financial, and transportation centers of the southeastern United States. Located in the northern portion of the state, Atlanta enjoys a high mean elevation—1,050 feet (320m) above sea level—which distinguishes it from most other southern (and eastern) cities and contributes to a more temperate climate than is found in areas farther south.

Atlanta was founded in 1837, a century after Savannah, the state’s oldest city.

History

The three dominant forces affecting Atlanta’s history and development have been transportation, race relations, and the “Atlanta spirit.” At each stage in the city’s development, these three elements have come into play. Transportation innovations and their connections to Atlanta helped establish the city as a state and regional center of commerce and finance. Issues of race and race relations, dating back to the years before the Civil War (1861-65), have affected the layout of the city and its political structure, municipal services, educational institutions, and sometimes conflicting images as a segregated southern city and a “Black mecca.” And the Atlanta spirit—part civic boosterism, part vision, with a healthy dose of business interests and priorities—has provided the city with an ever-changing set of goals and definitions of what Atlanta is and what it can become.

Railroad Terminus

Atlanta owes its origins to two important developments in the 1830s: the forcible removal of Native Americans (principally Creeks and Cherokees) from northwest Georgia and the extension of railroad lines into the state’s interior. Both of these actions sparked increased settlement and development in the upper Piedmont section of the state and led to Atlanta’s founding.

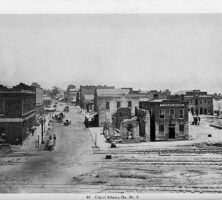

Indian removal and the discovery of gold encouraged new settlement in the region, but it was the railroad that actually brought Atlanta into being and eventually connected it with the rest of the state and region. In 1837 engineers for the Western and Atlantic Railroad (a state-sponsored project) staked out a point on a ridge about seven miles east of the Chattahoochee River as the southern end of a rail line they planned to build south from Chattanooga, Tennessee. The town that emerged around this zero milepost was called Terminus, which literally means “end of the line.” Had this remained the town’s only rail connection, Atlanta might well have stayed a small, end-of-the-line frontier town. By 1846, however, two other railroad lines had converged with the Western and Atlantic in the center of town, connecting it to far-flung areas of the Southeast and spurring the city’s growth.

In 1843 the name of the town was changed to Marthasville, in honor of the daughter of former governor Wilson Lumpkin, who had played a key role in bringing the railroad to the area. Two years later the city adopted a new name—Atlanta. Supposedly a feminine version of the word Atlantic, the name was first used by John Edgar Thomson, chief engineer of the Georgia Railroad, to designate his railroad’s local depot. Governor Lumpkin, on the other hand, is said to have maintained that the city’s new name was yet another tribute to his daughter, whose middle name was Atalanta, although this story appears to be apocryphal.

Civil War

By 1860 Atlanta was home to 9,554 people and was already the fourth largest city in the state. Enslaved African Americans and free persons of color were part of this population, although in smaller numbers than in the older, larger port cities of the South. The activities and freedoms of both groups of African Americans, however, were strictly controlled by laws and customs. Gatherings of enslaved and free Blacks, for example, required special sanction by the mayor; both groups had to observe strict curfews, and free persons of color could not live within the city limits without written permission of the city council.

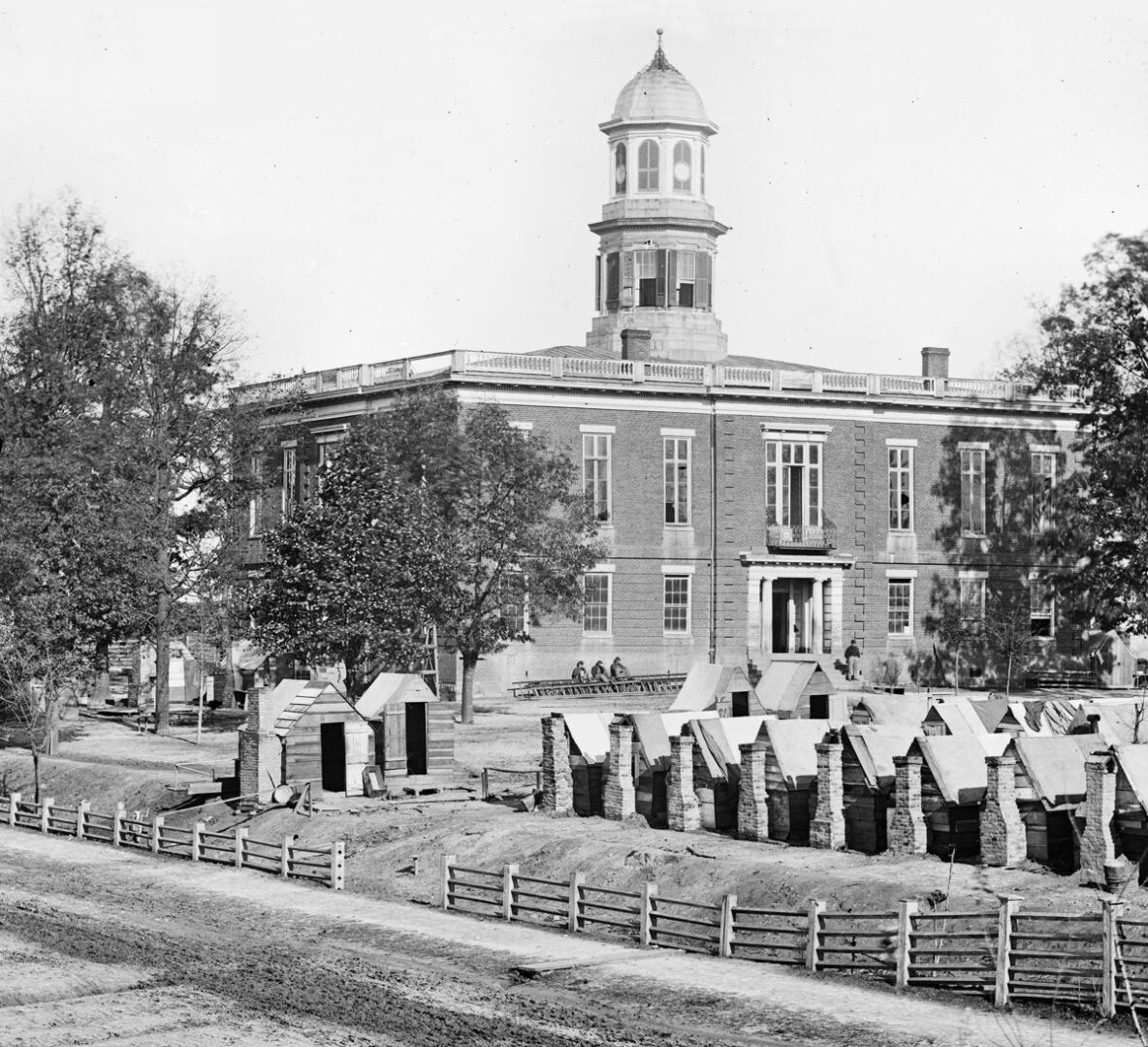

Antebellum Atlanta was a city led by merchants and railroad men, not planters, and as sectional differences mounted, businessmen and voters in the city tended to oppose secession, often on economic grounds. In the presidential election of 1860, the majority of voters cast their ballots for Union candidates Stephen A. Douglas and John Bell. But when Georgia seceded in January 1861, Atlanta joined with the Confederacy and rapidly became a strategically important city for the Southern cause. Railroad engineer Lemuel Grant, the chief engineer of the Confederate Department of Georgia, was responsible for fortifying the city.

The remaining Unionists in Atlanta, whose numbers have been estimated at about 100 families, faced increased pressures to conform or leave town. For example, the Committee on Public Safety, organized in 1861, and the Vigilance Committee, formed the following year, focused much of their attention and energies on ferreting out suspected spies and exposing abolitionists and Union sympathizers. As a result many Unionists left the city, and most of those who remained either went underground or kept a very low profile.

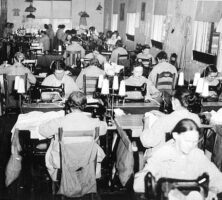

During the Civil War Atlanta became a home front, a major producer of war materials, and an important regional transportation and distribution center. Many existing industries in the city were soon converted to wartime production, and newly established factories provided much-needed Confederate munitions and supplies. Included among these new industries were the Atlanta Sword Manufactory and the Spiller and Burr pistol factory. The biggest ordnance producer in the city, however, was the Confederate government arsenal, which produced percussion caps for muskets and pistols, small arms ammunition, saddles, bridles, cartridge boxes, canteens, and other military items and employed more than 5,000 men and women. A second large war-related industry and producer was the Quartermaster Depot, which operated a shoe factory, a tannery, and a clothing depot that employed more than 3,000 seamstresses. These industries and the employment opportunities associated with them swelled Atlanta’s population from 9,000 people in 1860 to some 22,000 four years later.

The same qualities that made Atlanta a strategically important town for the Confederacy also made it a tempting target for Union armies, and in the summer of 1864 General William T. Sherman and his troops moved closer on their Atlanta campaign. From July 20 to August 25 Atlanta was subjected to a withering aerial bombardment. In the process a number of civilians were killed, and property and buildings in the city were badly damaged.

On September 2, 1864, Sherman’s troops captured the city, and the remaining residents (about 3,500 people, according to one estimate) were ordered to evacuate. Before Sherman’s army departed on its famous March to the Sea, however, fire and Union soldiers demolished the city’s railroad depots, the roundhouse, the machine shops, and all other railroad support buildings. Public buildings, selected commercial enterprises, industries (including the Winship Foundry and the Atlanta Gas Light Company, which were operated by Union sympathizers), military installations, and blacksmith shops were also targeted. Sherman’s instructions called for engineers to level the buildings before they were torched, but eager and careless soldiers set fire to many structures before the engineers arrived. As a result many Atlanta homes and businesses not marked for destruction were also consumed in the fires that swept the city on November 15, 1864.

Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in 1864 had far-ranging repercussions. It secured Abraham Lincoln’s U.S. presidential election victory in the fall of that year. It also ultimately doomed the Confederacy and its fading hopes for victory and independence. Finally, it left Atlanta burned, barren, and bankrupt.

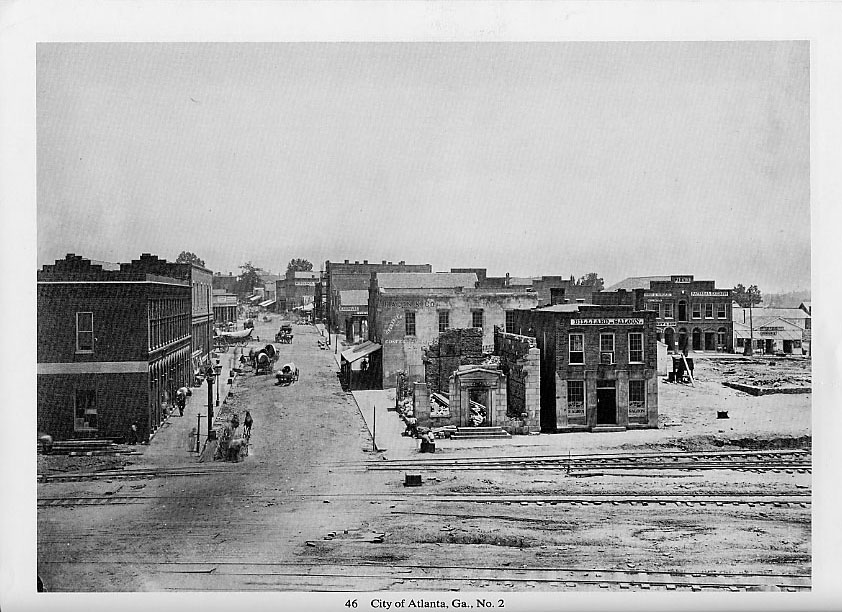

A New South City

The scene that greeted those Atlanta residents who returned to the city in 1864-65 was grim indeed. Much of the city lay in burned ruins, the railroad lines—the lifeblood of Atlanta—were destroyed, and there was only $1.64 in worthless Confederate currency in the city treasury. Despite these austere conditions, Atlanta emerged from the ashes to rebuild quickly—bigger, noisier, and with even greater ambitions and goals than before.

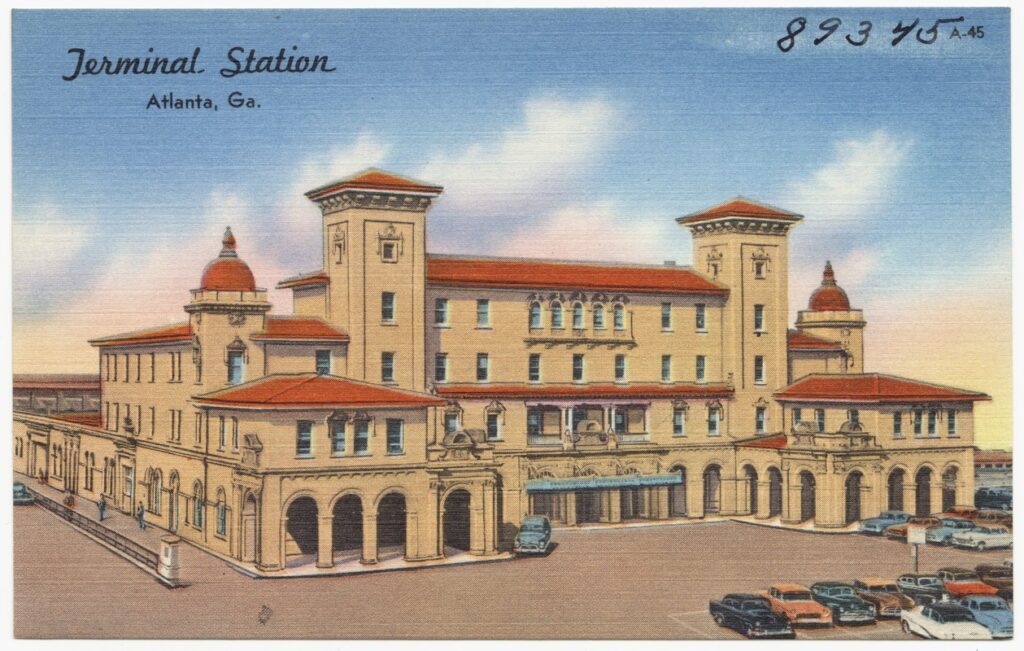

The same force that had contributed so greatly to Atlanta’s founding and early growth—the railroads—once again spurred the city’s development after the war. By fall 1865 all five of the city’s rail lines were again operational, and by the turn of the century, fifteen lines passed through the city, with more than 150 trains arriving in Atlanta every day. The impact of the railroads was felt all over the city. Railroads lay at the heart of the local economy, swelled the city’s numbers, connected Atlanta to distant markets, shaped its physical layout, and supported Atlanta’s grandiose claims to being the “Gate City” to the region and the “Chicago of the South.”

Because of the city’s important railroad connections, both wholesale and retail trade increased in the post–Civil War period, and by 1890 Atlanta was a clear leader in the region’s commercial development. Industrial development also increased, and although the city never became an industrial center like Birmingham, Alabama, about a third of its economic base in the 1880s was tied to manufacturing, including a large number of enterprises connected to railroads and cotton processing. Atlanta’s increasing size and regional importance was also underscored by the city’s selection in 1868 as Georgia’s new state capital, replacing Milledgeville.

As Atlanta’s economy grew and diversified, so too did its population. Between 1865 and 1867 almost 20,000 people moved to the city, and by 1900 the population had grown to almost 90,000. Atlanta was now the largest city in the state and the third largest in the Southeast. Adding to this growing population were large numbers of African Americans, drawn to the city by opportunities for education and employment. In 1860 African Americans in the city numbered less than 2,000; by 1900 there were more than 35,000 Black Atlantans—approximately 40 percent of the total population of the city.

Many of these new African American residents clustered in segregated neighborhoods or communities adjacent to emerging Black institutions of higher education—in east Atlanta in the Old Fourth Ward, where Morris Brown College was originally located; on the south side, where Clark College (later Clark Atlanta University) was first established; and on the west side, where Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) and later Spelman and Morehouse colleges were located. Elsewhere, Black Atlantans were largely confined to low-lying, flood-prone areas and other less desirable sections of the city. Despite these restrictions, the presence of this strong nucleus of Black colleges and growing economic opportunities laid the foundation for an emerging and influential Black middle class.

Among Atlanta’s white business and civic leaders, the city’s goals were oriented around a new vision for the region called the “New South” philosophy, which was ably promoted and popularized by local newspaper editor Henry W. Grady. In his many editorials and speeches on the subject, Grady emphasized that the region’s and Atlanta’s best hope for growth and prosperity lay in reconciliation with the North, more industry, less dependence upon cotton and staple crop agriculture, and a more diversified economy. Better education (particularly in industrial technology and engineering) was also an important component of this philosophy, and in 1888 the Georgia Institute of Technology opened its doors in Atlanta to address this need. Other white institutions of higher education in Atlanta included Oglethorpe University, which reopened after the Civil War, and Agnes Scott College for women, which opened in Decatur in 1889 and became the first college in metropolitan Atlanta to be accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

Henry Grady and other business and civic leaders of Atlanta during this period looked for opportunities to showcase the potential of the city and the New South, and one of their favorite devices was the grand fair or exposition. In 1881 Atlanta hosted the International Cotton Exposition, which drew 350,000 people from thirty-three states and seven foreign countries, and in 1887 the Piedmont Exposition opened with U.S. president Grover Cleveland in attendance. The grand showcase of them all, however, was the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, which featured buildings and exhibits devoted to minerals, agriculture, forestry, manufacturing, railroads, transportation, and electricity. Modeled on the Chicago Columbian Exposition (held two years earlier), the 1895 exposition also added a building devoted to the “New Woman” and a “Negro Building,” designed, constructed, and managed by African Americans and intended to highlight the accomplishments and potential of Black southerners.

The Negro Building’s separate status at the exposition paralleled the increasing separation of the races that was occurring in Atlanta and elsewhere throughout the South. By the turn of the century, segregation ordinances and regulations (commonly known as “Jim Crow”) were firmly in place to keep the two groups apart and define their respective rights, privileges, and social status. When Booker T. Washington, the most widely recognized Black educator in the country, addressed the opening day crowds at the 1895 exposition, he provided a prescription for Black development and progress that seemed to condone Jim Crow. White leaders of Atlanta and the South applauded Washington’s approach; critics labeled his speech the “Atlanta Compromise.”

“Forward Atlanta”

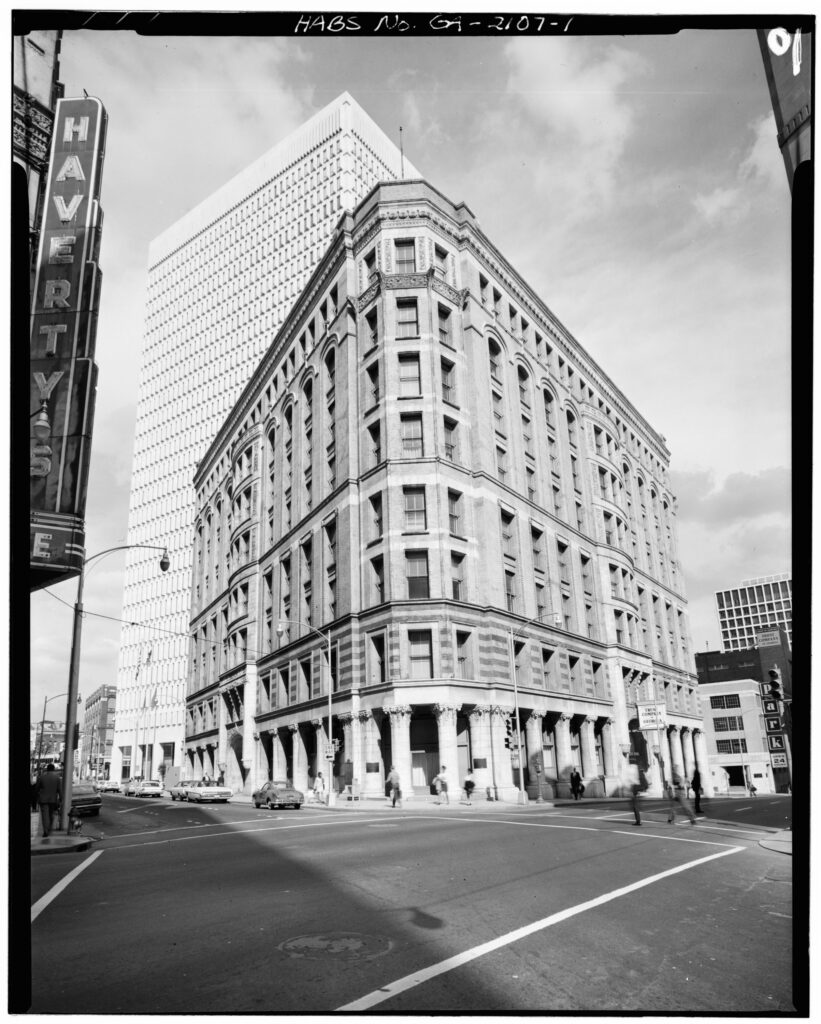

As the new century dawned, Atlanta experienced a period of unprecedented growth. In three decades’ time the city’s population tripled, and the city limits expanded to add new communities like Edgewood, Kirkwood, and West End to its boundaries. Beyond the city limits new suburban developments arose, made possible by the presence first of the streetcar and later of the automobile. Even Atlanta’s skyline began to expand and change with the addition of the city’s earliest skyscrapers—the Equitable, Flatiron, Empire, and Candler buildings—and new commercial and government structures.

Atlanta’s explosive growth was regarded by most city boosters as a positive development, one that ought to be promoted and encouraged. Louie Newton, editor of the City Builder magazine, lauded what he termed the “Atlanta Spirit”—the pervasive belief that whatever was good for business was good for Atlanta and all Atlantans. In the name of business and progress, the city’s early-twentieth-century boosters encouraged not only commercial growth but also the development of a myriad of cultural, artistic, and sports activities and institutions that they hoped would transform Atlanta into an urban center of regional and national prominence. In the process of promoting and implementing these changes, Atlanta was remade and its economic, cultural, and physical structure dramatically altered.

Atlanta’s early-twentieth-century growth and expansion was based in part on the development of a new economic orientation for the city. In the nineteenth century the city’s economy had been centered on the railroad. In the following century the railroad’s economic impact (though still significant) lessened, and Atlanta featured a more diversified economic order based on commerce and the establishment of the city as a regional business center. In 1925 Ivan Allen Sr. and W.R.C. Smith of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce launched a national advertising campaign entitled “Forward Atlanta,” which was designed to lure new businesses to the city and to encourage national corporations to establish their regional headquarters there. The campaign was extremely successful, bringing thousands of jobs and adding an estimated $34 million in annual payrolls to the city’s economy. Included among these businesses were such giants as Sears-Roebuck (which built its southeastern retail and mail-order headquarters in Atlanta) and General Motors (which established a manufacturing plant in the city).

On the other side of the color line, a separate business and entertainment district for African Americans was growing along Auburn Avenue. With the rise of Jim Crow and increased racial violence and hostility (including a 1906 race massacre), Black businesses began to locate along the avenue in the old Fourth Ward, where a sizable African American residential community and influential Black churches (such as First Congregational, Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal, Wheat Street Baptist, and Ebenezer Baptist) were already present.

Black-owned and-operated office buildings and multi-use structures (like the Rucker, Odd Fellows, and Herndon buildings), entertainment centers (like the Top Hat Club), insurance companies (Standard Life Insurance and Atlanta Life Insurance companies), stores, banks and lending institutions (Citizen Trust Bank and Mutual Federal), hotels, restaurants, beauty schools, funeral homes, and newspapers (including the Atlanta Independent and later the Atlanta Daily World) were all located along the street that John Wesley Dobbs, a Black fraternal, political, and civic leader, would dub “Sweet Auburn.” As the Atlanta Independent observed in 1926, Auburn Avenue “is an institution with influence and power not only among Georgians but American Negroes everywhere. It is the heart of Negro big business, a result of Negro cooperation and evidence of Negro possibility.”

Auburn Avenue was also the by-product of rigid segregation, and Martin Luther King Jr., who was born on Auburn Avenue and whose father and grandfather were preachers at nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church, witnessed firsthand both the bright promise and the disheartening racial discrimination that Auburn Avenue represented.

Race and race relations also played a part in the distribution of municipal services, as the city worked to build the infrastructure necessary to support rapid urban growth. For much of the early twentieth century, water and sewer lines in Atlanta lagged behind population growth, many roads remained unpaved, public schools were overcrowded and underfunded, and health care and social services were inadequate to the task at hand. Each of these problems was even more acute in the city’s Black neighborhoods and communities. (As late as 1941-42, for example, the city spent less than 16 percent of its annual school funds on African American students.) To help remedy some of the problems facing Atlanta, city voters (including registered Black voters) passed a $3 million bond referendum in 1910, the largest to date, and another bond referendum in 1921, which not only helped address some of the educational needs facing white students but also provided funds for the construction of Atlanta’s first Black public high school—Booker T. Washington—which opened on the west side of Atlanta in 1924.

As the city’s population swelled, racial and ethnic tensions grew as well. In 1906 a violent race massacre broke out in Atlanta. When the bloodshed finally ended, the city officially listed twelve dead (ten Black and two white) and seventy injured, although newspaper accounts reported a much higher number of deaths. The city also listed hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of property damage to Black businesses and homes. In 1913 tensions and emotions erupted again during the trial of Leo Frank, a Jewish businessman, accused of the murder of Mary Phagan, a young white factory worker. Frank’s trial was marked by sensationalist press coverage and virulent anti-Semitism, and in the end he was found guilty. In 1915, after his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, Frank was forcibly taken from his Milledgeville jail cell by a mob and lynched in Marietta.

Both the race massacre and the Leo Frank lynching had far-ranging results. The Frank case brought about important changes in the legal system and encouraged the local Jewish community to form the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith. The 1906 race massacre also contributed to the formation of local organizations dedicated to easing racial tensions and violence, such as the Commission on Inter-Racial Cooperation and the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. Both events also contributed, in part, to the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan. Reborn on Stone Mountain in 1915, the Klan made its headquarters in Atlanta (designated the “Imperial City of the Invisible Empire”). By 1923 the city’s Nathan Bedford Forrest Klan No.1 had a membership of more than 15,000, including many notable businessmen, educators, clergy, and politicians.

At the same time that racial barriers were being established and strengthened in the city, the patterns of Atlanta’s residential and municipal development were also being affected by the arrival of a new mode of transportation—the automobile. The automobile’s growing use in downtown Atlanta contributed to the creation of a series of viaducts to raise the city’s streets above the railroads and railroad lines and grade-level crossings. The automobile also helped disperse the city’s residential population farther into the suburbs, sparking a suburban real-estate boom and the creation of a ring of middle-class, bungalow-style houses and communities two to five miles from downtown. Included in this ring were Home Park and Virginia Highland on the north, Candler Park/Edgewood on the east, Sylvan Hills and West End on the south, and Washington Park—a Black suburban development—on the west side. The automobile also encouraged Atlanta’s white elite to move away from the center of the city—particularly to the north. By 1930 almost half of all Atlantans listed in the Social Register lived north of Ansley Park—many of them in Buckhead, which grew from a population of 2,603 in 1920 to 10,356 ten years later.

Automobiles were not the only new mode of transportation to make its mark in this period. The airplane also made its appearance in the city in the 1920s, and by the end of the decade, Atlanta had an airfield, a passenger terminal, air mail and passenger routes, and an early connection with the airline industry that would serve the city well in the future. The person most responsible for establishing this air connection was a young city councilman who would later become the longtime mayor of Atlanta—William B. Hartsfield.

By the eve of World War II (1941-45), Atlanta was the center of an impressive network of air-, car, and rail lines. The construction of a highway link to Savannah in 1935 and Georgia’s first “superhighway,” running between Atlanta and Marietta, in 1938 was also establishing the city’s importance as a regional trucking center. In the decades to follow, these transportation links expanded and grew in importance as Atlanta established its preeminent position as the transportation capital of the Southeast.

The Great Depression and World War II

The growth and prosperity that characterized Atlanta during the early decades of the twentieth century were shaken by the severe economic depression that gripped the nation in the 1930s. Like many cities in the South, Atlanta was poorly prepared to meet the emergency. In fact, Atlanta ranked last among similar-sized cities in the nation in 1930 in terms of its per capita expenditures for welfare, and there were few municipal agencies or programs in place to help the rapidly growing number of unemployed.

Relief for unemployed and underemployed Atlantans finally arrived in the early 1930s with the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt as U.S. president and the institution of his New Deal legislation and programs. Atlanta took full advantage of the funds and resources made available by these New Deal programs and became one of the first cities in the nation to have a federally operated relief program. Agencies such as the Civil Works Administration, the Public Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) pumped millions of dollars into Atlanta projects and employed thousands of city residents in the process. Projects undertaken by these agencies included the building and repair of area schools, hospitals, gymnasiums, and other public institutions; the grading of runways at the city’s airport, Candler Field; the organization of a symphony orchestra; the repair and touchup of the Cyclorama, a 358-foot-in-circumference mural depicting the Civil War Battle of Atlanta; and the construction of a new sewer system.

The New Deal also spurred the construction of the nation’s first public housing projects—Techwood Homes for whites, which opened in 1935, and University Homes for African Americans, which opened in 1938. The idea for these projects had originated with an Atlanta real estate developer, Charles F. Palmer, who wished to rid the city of some of its slums and replace them with federally funded public housing. Also involved in lobbying for this public housing was John Hope, president of Atlanta University.

By the late 1930s the severity of the depression in Atlanta was beginning to lessen. Private business was picking up, the federal government trimmed the number of WPA workers in the city, the banks were all back in operation, and aviation continued to be a growth industry for Atlanta. It would take World War II and the industrial development and expenditures associated with that effort, however, to return Atlanta to full prosperity and launch the city into a new era of growth and transformation.

World War II (1941-45) was a watershed event for the South in general and Atlanta in particular. Between 1940 and 1945 the federal government invested more than $10 billion in war industries and military bases located in the South. It expended millions more on such related projects as public housing, health-care facilities, and aid to schools near military facilities. In Atlanta these wartime activities helped end the depression; swelled the city’s population; spread a broad net of federal installations throughout the metropolitan area; enlisted Blacks and whites, men and women, in the armed forces and in war-related industries; and brought to the forefront forces that would dramatically affect the city’s race relations and politics in the post–World War II era.

Thousands of soldiers and military support personnel passed through or were stationed in Atlanta during the war at area bases and support facilities, including Fort McPherson, Fort Gillem, the Naval Air Station, and the Army Hospital and Airfield. War-related industries also played a key role in the local economy. About 100 Atlanta businesses devoted their total output to the war effort. The largest of these operations was the Bell Bomber (later, Bell Aircraft) plant, located in Marietta, which employed 28,158 workers (including a sizeable number of women and African Americans) at its peak in 1945. Another famous Atlanta business connected with the war effort was Coca-Cola, which distributed Cokes to servicemen and -women around the world during the war for five cents a bottle and, in the process, became a truly international corporation. Also during this time, the forerunner of Atlanta Technical College was established in downtown Atlanta, and offered vocational training.

Postwar Developments: Hartsfield and Allen Administrations

The industrial and business growth that occurred during World War II continued and accelerated in Atlanta during the postwar years. In 1947 a new Ford automobile assembly plant was opened in Hapeville, and the following year General Motors opened a new factory in Doraville. Bell Aircraft, the city’s biggest wartime employer, scaled down drastically beginning in mid-1945 but reopened as Lockheed-Georgia in early 1951. By 1954 there were 800 new industries in Atlanta and almost 1,200 national corporations with offices in the city.

Rapid population growth accompanied this postwar economic activity, and Atlanta expanded its borders to accommodate the growth. In 1952 the city annexed an additional 82 square miles, adding 100,000 new residents. Highways and freeways were also built and expanded to meet the city’s growing need. Well before federal money became available in the late 1950s under the interstate highway program, Atlanta was already working on its freeways—an approach that allowed the city to link up later with three major interstate highways that connected Atlanta to the region and fed suburban metropolitan growth. Highway construction (combined with urban renewal activities) also lowered the supply of Black housing within the city—displacing almost 67,000 people in the period from 1956 to 1966 and adding to an already severe housing shortage. By 1959 African Americans made up 36 percent of the city’s population but occupied only 16 percent of the available residential land.

In the 1960s the traditional color line in housing, education, and politics in Atlanta began to crumble as African Americans asserted their increasing political power and the civil rights movement began to focus attention and energy on the overthrow of Jim Crow. In 1961 Black college students began a sit-in movement to desegregate downtown restaurants and other public facilities. That fall, the city also began the court-ordered desegregation of its public schools as 9 Black students (chosen from a pool of 133 applicants) peacefully integrated four Atlanta high schools—Brown, Henry Grady, Murphy, and Northside.

Another important racial barrier fell in 1962, when courts ordered the removal of city barricades along Peyton Road in southwest Atlanta that had been erected to prevent Black residential expansion into that area’s majority white neighborhoods. This decision opened up new areas of the city for Black residential development (particularly in southwest Atlanta). It also accelerated the exodus of white Atlantans to the suburbs. During the 1960s the white population of the city declined by 60,132, while the Black population increased by 68,587. The 1970 census revealed that Atlanta had a majority Black population for the first time in the city’s history.

Changes in the racial makeup of the city were accompanied by equally important changes in the political structure of Atlanta. In 1969 Maynard Jackson was elected the city’s first African American vice mayor (along with Sam Massell, the city’s first Jewish mayor), and in 1972 Andrew Young, a colleague and aide of Martin Luther King Jr., became the first Black congressman from Georgia since Reconstruction. Black representation in the Georgia legislature also increased during these years, and a sea change in local politics occurred in 1973, when Maynard Jackson became Atlanta’s first African American mayor and Blacks gained equal representation on the city council and a slight majority on the school board.

As dramatic and sudden as these changes seemed to be, they were actually the result of a series of events, legal challenges, court victories, and grudging but gradual accommodations to increasing Black political strength that began in the years after World War II. The repeal of the poll tax by the Georgia legislature in 1945 and the invalidation of the white primary by the U.S. Supreme Court the following year, for example, removed two very important barriers to Black participation in state and local elections. The greatest impetus to increased Black voter registration in Atlanta, however, was a very successful and well-organized registration drive created and organized in 1946 by a number of Black political and civic organizations, leading to the formation of the Atlanta Negro Voters League. As a result of this drive, almost 14,500 new African American voters in Atlanta were added to the rolls in three months. While still a political minority, Blacks were gaining growing electoral strength, which convinced Mayor William Hartsfield to begin seeking African American support and to start addressing some issues of concern to the city’s Black communities through quiet, behind-the-scenes negotiations.

The interests and goals of the city’s white business leaders—always an important element of the Atlanta Spirit—also had a major impact on the city’s approach to civil rights during this era. Such business leaders as Coca-Cola CEO Robert Woodruff were concerned about Atlanta’s image in national business circles and wished to avoid the racial violence and disturbances that had beset other southern cities, including Little Rock, Arkansas, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Birmingham, Alabama. Hartsfield is credited with coining the slogan “the City Too Busy to Hate” to draw attention to this regional distinction, and although the fall of Jim Crow was agonizingly slow at times, Atlanta was at least spared major racial unrest.

Hartsfield’s successor, Ivan Allen Jr., the son of a prominent local businessman and a former president of the chamber of commerce, also recognized the importance of the city’s reputation and its continued attractiveness to national corporations. After an initial unsuccessful attempt to block Black residential expansion, Allen became an advocate of civil rights and a strong supporter of Martin Luther King Jr.’s attempts to end segregation and advance equal rights. In 1963 he testified before the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee in favor of a civil rights bill—the only southern elected official to do so.

Allen’s plans for Atlanta in the 1960s also called for the construction of new public facilities, continued business growth, additional low-income housing (to replace dwellings lost to urban renewal and highway construction), and the development of a mass transit system. By the end of his term of office in 1969, many of these changes had taken place or were in process. Urban renewal had cleared large tracts of the city, and in some of these areas, new public housing and public facilities (including a civic auditorium) had been built.

The construction of a new sports stadium (Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium ) on land cleared by urban renewal also helped realize Atlanta’s dream to become “a big league city.” Both the Atlanta Braves baseball team (which moved from Milwaukee in 1966) and the Atlanta Falcons football team (which began play in the fall of that year) initially played their games in this new stadium, and other professional sports teams soon followed. In 1968 the Atlanta Hawks basketball team relocated to the city from St. Louis, Missouri, and in 1972 the Atlanta Flames (later the Calgary, Alberta, Flames) of the National Hockey League opened play in the Omni—a $17 million entertainment and sports facility that both teams would share.

Continued business growth was promoted through a second “Forward Atlanta” campaign, which, much as its predecessor had done forty years earlier, advertised the unique resources and potential of the city. Once again the campaign was a success, luring many new businesses to Atlanta. Business growth was accompanied by a vertical expansion of the city through the construction of new skyscrapers and office buildings. High-rise hotels were a key component of this development, representing both the increasing economic importance of the hospitality and tourism industry to the city and the impact of local architect John Portman. Portman’s design and construction of a complex of office towers, hotels, retail shops, restaurants, and convention space, known as Peachtree Center, spurred additional high-rise construction in the downtown area (seventeen buildings of more than fifteen floors were built in the 1960s) and helped reposition the commercial center of the city farther north along Peachtree Street.

Transportation, always an important factor in Atlanta’s growth and development, had a significant impact on the city in the 1960s and 1970s. Atlanta’s connections to three interstate highways continued during this period to direct and facilitate suburban growth and anchored the regional trucking industry to the city. Air travel also became increasingly important as Atlanta Municipal Airport (later Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport) emerged as one of the busiest air hubs in the nation. In 1961 the airport opened an $18 million air terminal, which handled 3.5 million passengers the first year. By 1970 the number of passengers had quadrupled to more than 14 million annually. Atlanta’s air connections to other U.S. cities (2,400 flights a day to 135 cities in 1980) in turn nourished the city’s tourism and convention business, helping Atlanta become the third busiest convention center in the country. Public transit—a key element in the plans for Atlanta during this era—also came into being in 1971 as voters approved by a narrow margin the funding and creation of the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA), which combined public bus routes with rapid rail service.

Suburban Metropolis and International City

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Atlanta experienced a continuation of a number of significant trends that had emerged in the years after World War II as well as the beginnings of new ones. Suburban growth and development continued and in fact accelerated, as the total number of residents in the metropolitan area grew from 2 million in 1980 to more than 4 million in 2000. Office buildings and retail establishments followed this population growth and movement to the suburbs, especially on the north side of the city. Racial divisions that had emerged between suburb and city during the 1960s remained evident, with the city retaining a majority Black population while the suburbs were majority white. The dramatic change that had occurred in the local political structure with the election of Maynard Jackson as the city’s first African American mayor also continued on course, as Jackson was followed in office by Black mayors Andrew Young (1982); Maynard Jackson again (1990); Bill Campbell (1994); Shirley Franklin (2002), the first woman in the city’s history to hold that office; Kasim Reed (2010); and Keisha Lance Bottoms (2018).

In the transportation sector airplanes and automobiles continued to have the biggest impact on the metropolitan region. In 1971 the Atlanta airport was rechristened Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport—in recognition of both the important role Hartsfield (who died that year) had played in the development of aviation in Atlanta and the city’s hopes to become an international destination and player in the world market. At that time the only true international connection at Hartsfield was a single Eastern Airlines route to Mexico City. A decade later, everything had changed. The deregulation of the airline industry in the late 1970s and the adoption of a hub-and-spoke system suited Atlanta and gained its airport an increasing number of international routes. Most importantly, a mammoth terminal had been built—at a cost of some $450 million, and with a quarter of those bids going to minority businesses. The new terminal was a signature achievement for Mayor Jackson who ensured that the work was completed “ahead of schedule and under budget.” In 2003 the airport was renamed Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in honor of Jackson’s contributions to the city. By then, Hartsfield-Jackson was the busiest airport in the world, carrying more than 78 million passengers.

Automobiles, the transportation mode that had done so much to shape the city in the first half of the twentieth century, continued to affect the layout and lifestyles of metropolitan Atlanta in the last decades of the century. As the numbers of residents in the outlying areas continued to grow, the Georgia Department of Transportation responded by increasing the number of passenger lanes on Interstates 85, 75, and 20 (including the construction of high-occupancy vehicle lanes to encourage carpooling, and later, the introduction of optional toll lanes, which allow motorists the option of avoiding congested routes—provided that they can afford the variable tolls) and also on Interstate 285, the high-speed, limited-access highway that encircles the city. Georgia 400, a toll road until 2013, was completed in 1993 and intended to connect suburban communities north of Atlanta to the city. By the turn of the century 2.5 million vehicles were registered in the metropolitan area, and motorists were driving approximately 100 million miles every day on Atlanta highways and roads.

MARTA, once envisioned as a cure for Atlanta’s dependence upon automobile travel and the city’s nonpedestrian orientation, did not fulfill either of these goals. Suburban counties resisted the expansion of MARTA rail and bus lines into their jurisdictions, and rights-of-way for rail expansion in other areas proved extremely costly. New rail stations and track were added, however, to the main north-south line, resulting in a rapid-rail route that stretches from the Chamblee-Dunwoody area in north DeKalb County through downtown Atlanta to the airport on the south side of the region. More recently the Atlanta BeltLine, an ambitious pedestrian and light-rail transit corridor scheduled to circle the city by 2030, opened its first segment in the city’s West End neighborhood in 2008.

The changes in Atlanta’s transportation sectors—especially at Hartsfield—also supported the city’s bid during this period to increase its convention and tourism business. The continued expansion of the World Congress Center (which was expanded in 2002 to total 1.4 million square feet of exhibition space), the potential revitalization of Underground Atlanta (a subterranean complex of shops, bars, and cafés on the original street level of the city that was sold to the real estate investment firm WRS Inc. in 2014 for $25.75 million), and the construction of sports facilities—Turner Field for the Braves (which was replaced by Truist Park in Cobb County and later redeveloped as Center Parc Stadium ), the Georgia Dome for the Falcons (which was demolished and replaced by Mercedes-Benz Stadium in 2017), and Philips Arena (later State Farm Arena) for the Hawks—contributed to this effort as well. These downtown facilities provided residents and tourists with increased options for entertainment and were seen as a way of combating the movement of most major retail and many commercial enterprises and industries to the outlying suburbs. Other additions to the city’s growing downtown entertainment and convention district include the Children’s Museum of Atlanta in 2003; the Georgia Aquarium in 2005; an enlarged World Coca-Cola museum in 2007; the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in 2014; and the College Football Hall of Fame in 2014.

The Atlanta Spirit, which had shaped the city’s changing notions of its status, orientation, and destination throughout its history, also came into play during this period as political and civic boosters continued to promote Atlanta as the “world’s next great city.” To be sure, there was some basis to Atlanta’s claim of international status in the 1980s and 1990s. By 1995, for example, more than 1,000 foreign companies from 35 foreign countries were located in the metro area, as well as 37 foreign consulates and 20 trade and tourism offices. Atlanta’s resident population was also becoming more diverse, as new ethnic and cultural groups from Central and South America, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean moved into the city and the surrounding metropolitan region in increasing numbers. In addition, many of Atlanta’s highest-profile businesses, such as Coca-Cola, Cable News Network (CNN), and United Parcel Service (UPS) were known throughout the world.

Perhaps the greatest indication of Atlanta’s rising international status, however, was the awarding of the 1996 centennial summer Olympic Games to the city. Most Atlantans considered the games a success, although some athletes and international visitors and journalists complained of inadequate lodging and transportation facilities. The Olympics were also marred by the explosion of a bomb that killed one person and injured more than 100 others. On the positive side, however, the games contributed to the construction and improvement of many public buildings and facilities in downtown Atlanta, including the Olympic Stadium (which became Turner Field) and the twenty-one-acre Centennial Olympic Park. The Olympic Village housing was converted to student housing for Georgia Tech and Georgia State University (GSU); in 2007 GSU transferred ownership of its portion of the former village to Georgia Tech.

These important trends in population growth, residential distribution and makeup, transportation, and business and commerce characterized a city and metropolitan area that at the turn of the twentieth century appeared to be vibrant, growing, and economically strong. There were some troubling signs as well, however, associated with these trends. Unchecked suburban growth and widespread automobile use, for example, contributed to difficult traffic problems and environmental issues, including increased pollution. From 1988 to 1998 the Atlanta area lost some 190,000 acres of tree cover to residential and commercial development in the suburban metropolis.

In 1999 the region endured a record sixty-nine days of smog alerts, and the average traffic commute of thirty-two minutes, already the longest in the nation, became even slower as well, as interstates and highways filled up with cars. Such issues caused legislators to make changes to the state’s environmental policy. Also in 1999 the Environmental Protection Agency ruled that Atlanta did not comply with the 1990 Clean Air Act—a decision that threatened to halt $1 billion in federal highway funds and an additional $700 million that had already been approved for highway projects before the ruling. The state government responded with urgent appeals to workers to telecommute and/or ride-share, and established the Greater Regional Transportation Authority with the power to create a regional public transit system and the ability to compel metro counties to pay for it.

The significant racial divide between city and suburb actually lessened somewhat toward the turn of the century as Black suburbanization increased and a small back-to-the-city movement among white Atlantans gained momentum—trends that only increased in the new century. Residential segregation continued, however, as did significant differences in income and job opportunities between inner city and suburban residents. At the turn of the century, the poverty rate for the entire metropolitan area was only 9.4 percent, while within the city it was 24.4 percent. Similarly, from 1980 to 1990 the central city’s share of jobs in the region dropped from 40 to 30 percent, while northern suburbs’ share rose from 40 to 52 percent.

As this historical overview suggests, problems as well as opportunities associated with urban growth, race, and transportation have long been a part of Atlanta’s history, and they are likely to influence the development and character of this city and region for years, and perhaps decades, to come.

Population Patterns

The city of Atlanta itself is relatively small, with a land area of just over 131 square miles. The city’s population, which peaked in 1970 at 496,973, shrank by some 71,951 people as that decade progressed and by another 31,262 in the 1980s. This trend of declining numbers now appears to have halted; in 2000 the total central-city population was 416,474 and in 2010 it rose to 420,003, making Atlanta the fortieth largest central city in the United States. By 2014 the city’s population had grown to approximately 456,000.

With few natural barriers to contain or restrict the region’s growth, the population of the Atlanta metropolitan area has continued to grow, from 2,029,710 in 1980 to 5,268,860 in 2010. During the 1990s Atlanta outpaced all other metropolitan areas in the United States except Phoenix, Arizona, in its rate of population growth, and in 2013 it ranked as the ninth largest metropolitan area in the country. The dispersed nature of Atlanta’s population and growth has contributed to its having one of the smallest population densities of all major metropolitan regions in the United States.

For much of its history Atlanta could be described as a biracial city, with whites and Blacks constituting the vast majority of the resident population. In 1940 only 1.4 percent of Atlanta’s population was foreign-born, and this figure was little changed a decade later. In the early 1980s, however, the ethnic and racial landscape of the city and the metropolitan area began to change, as private relief agencies resettled refugees from Southeast Asia, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and Eastern Europe in the area and Atlanta’s booming economy and job opportunities drew large numbers of immigrants from Mexico and other countries in Central and South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and West Africa. By 2014 Hispanics constituted 5.2 percent of the city population, Asians made up another 3.1 percent, and those of two or more races totaled 2 percent. In the metropolitan area as a whole, a similar change has been occurring. Census data from 2010 also indicate that approximately 13.5 percent of the metropolitan population is now foreign-born.

Despite these changes, the two largest population groups in the Atlanta metropolitan area continue to be African Americans and whites, with African Americans constituting a majority presence within the city (54 percent in 2014, down from 61.4 percent in 2000) and whites the predominant residential group in the suburbs (66.3 percent in 2000). That pattern continues to change as whites move into the city and Black suburbanization continues to accelerate. (Between 2000 and 2002, for example, more than 9,000 new white residents moved into the city.) In addition, Atlantans, both Black and white, according to recent surveys, are now more willing to live in integrated neighborhoods—a Brookings Institution study noted that the number of metropolitan Atlanta residents living in the most integrated neighborhoods rose by 2,500 percent during the 1990s (while the number in the most segregated areas dropped by 39 percent). Residential segregation of the races is still very evident, however, and according to an Associated Press analysis of 1990 and 2000 Black-white housing patterns, Atlanta remains the most segregated city in Georgia and the second most segregated city in the nation (behind Chicago, Illinois).

Economy

Atlanta’s dramatic population growth in the last few decades has been matched by equally impressive economic growth. The city is, by most measures, the business capital of the Southeast. It is also the headquarters for some of the nation’s (and the world’s) best-known companies, including Coca-Cola, CNN, UPS, Georgia-Pacific, the Home Depot, and Delta Air Lines. In addition to these corporate giants, more than four-fifths of the nation’s largest businesses maintain branch offices in the metropolitan area.

Atlanta’s economy is also tied closely to government agencies and activities, transportation, and the hospitality and convention industry. As the capital of Georgia, the city is host to a wide assortment of state departments and agencies. The Atlanta metropolitan area also has the largest concentration of federal agencies outside of Washington, D.C., including the national headquarters for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dobbins Air Reserve Base continues as an active military installation, while Naval Air Station Atlanta closed in 2009, followed by Fort McPherson in 2011. Taken as a whole, these governmental bodies constitute one of the metropolitan area’s largest employers and a force that has exerted considerable influence in the last five decades on Atlanta’s development and changing economy. In fact, with the increasing movement of jobs, retail industries, and office buildings to the urban perimeter, the local, state, and federal government presence in downtown Atlanta has proven to be one of the area’s stabilizing influences.

Atlanta’s ties to transportation include Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (one of the top two busiest airports in the world), three interstate highways that intersect in Atlanta, and a nexus of freight and passenger rail lines. All of these transportation connections bring commerce, products, and people to the Atlanta area and provide employment, either directly or indirectly, to many of the region’s citizens.

Since the 1970s the hospitality, tourism, and convention industry has been another key element of Atlanta’s economy, spurring the construction of new hotels, convention spaces, and related industries. From 1965 to 1975, for example, the number of hotel rooms in the downtown area alone increased from 4,000 to 14,000, and by 1972 Atlanta ranked third among cities (trailing only Chicago and New York) in terms of convention business. Facilitating this growth was the construction of such large support facilities as the Merchandise Mart (which opened in 1961 and was expanded in 1968), the Civic Center (1965), the Apparel Mart (1979, expanded in 1989), and the Georgia World Congress Center (opened in 1976). By 2000 more than 3 million people a year attended conventions in Atlanta and stayed in the metropolitan area’s 88,000 hotel rooms.

The Arts

Atlanta is home to a thriving arts community, with dozens of art museums, a professional ballet company, a puppetry arts center, and many performance spaces for theater, music, and dance. The Atlanta Ballet is the oldest professional dance company in America, as well as the largest self-supported arts organization in Georgia. The Atlanta Ballet performs at the Fox Theatre and the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Center.

Atlanta’s theater scene is a vibrant one, offering such established venues as Actor’s Express, Alliance Theatre, Dad’s Garage Theatre, Fox Theatre, Horizon Theatre Company, SCADshow, 7 Stages Theater, Shakespeare Tavern, and Theatrical Outfit. The Center for Puppetry Arts was the first puppetry center in the United States, and features performances and a hands-on museum that includes the Jim Henson Collection.

The High Museum of Art is the premier art museum in the Southeast, with a collection of more than 11,000 works of art, including American, African, folk, decorative, modern and contemporary, and photography. Other important museums are the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, the Museum of Design (which is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.), and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. Cultural, science, and historical museums include the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum, the Atlanta History Center (featuring three historic houses, the Margaret Mitchell House, Swan House, and Tullie Smith Farm; the Atlanta History Museum; the James G. Kenan Research Center; and thirty-three acres of landscape and historic gardens), the African American Panoramic Experience Museum (APEX), and the Fernbank Museum of Natural History.

Classical music has a long tradition in Atlanta. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra performs hundreds of concerts annually and has received international acclaim for its performances and recordings. The Atlanta Chamber Players are among the finest chamber music groups.

The Woodruff Arts Center, a state-of-the-art complex, is the jewel in Atlanta’s crown and is home to the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, the Alliance Theatre, the Atlanta College of Art, and the High Museum of Art, which was designed by the noted postmodern architect Richard Meier.

Sports and Recreation

Atlanta claims a number of major-league sports teams: the Braves baseball team; the Falcons football team; the Hawks basketball team; and Atlanta United FC, a soccer club. The Atlanta Motor Speedway hosts NASCAR events. The PATH Foundation has created more than 60 miles (with up to 200 to be created eventually) of multi-use greenway trails that wind through Atlanta’s neighborhoods and metro areas. Other recreational features in the city include Zoo Atlanta, the Chattahoochee Nature Center, Piedmont Park (the city’s largest public park and the site of the 1895 International and Cotton States Exposition), Centennial Olympic Park (the largest urban park built in the United States in the last twenty-five years), and the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

Sections of the City and Points of Interest

Downtown

Atlanta is sometimes described as a “horizontal city.” With few natural barriers to contain or restrict its growth, and greatly influenced by the arrival of the automobile and the increased mobility that it brought, the city has developed in a sprawling, dispersed fashion. Population density is lower in the downtown area than in many large, older cities, such as Chicago, Boston, or New York. Nonetheless, the tallest and most closely grouped buildings in Atlanta are found in Five Points (the original and geographic center of the city) and immediately north along Peachtree Street. The downtown area also contains, north of Five Points, the Georgia World Congress Center, Georgia Dome, CNN Center, State Farm Arena, Centennial Olympic Park, the Civic Center, Georgia Institute of Technology, the Fox Theatre, and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center.

The Georgia Aquarium, one of the largest aquariums in the world, opened in downtown Atlanta in November 2005. Funded by Home Depot cofounder Bernie Marcus, the facility contains 8 million gallons of water and houses more than 100,000 marine and freshwater animals. The aquarium has dedicated 25 percent of its public space to educational programs, and scientists at the facility conduct research in such areas as marine veterinary medicine and global conservation.

To the east of Five Points is Georgia State University, Auburn Avenue (with many historic structures and important institutions, including the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site and the Martin Luther King Center for Nonviolent Social Change), and historic Oakland Cemetery. South of Five Points are Underground Atlanta, the World of Coca-Cola, the state capitol, city hall, and Grant Park (containing Zoo Atlanta).

To the west of Five Points in downtown Atlanta is the Atlanta University Center, which is the largest consortium of Black colleges and universities in the nation. The Atlanta University Center includes Spelman College, Morehouse College, Morris Brown College, Clark Atlanta University, the Interdenominational Theological Center, and the Morehouse School of Medicine. Also in the Atlanta University area is the residence of Atlanta’s first Black millionaire, Alonzo Herndon, who founded Atlanta Life Insurance Company.

North

To the north of downtown is Midtown Atlanta, which features another grouping of tall office and hotel buildings, residential communities, restaurants, and bars. Also found in this section of the city are Ansley Park (an early-twentieth-century residential community), the Atlanta Botanical Gardens, Piedmont Park, the Margaret Mitchell House, the Woodruff Arts Center, Rhodes Hall, the Center for Puppetry Arts, and the Museum of Design.

Farther to the north along Peachtree Street is Buckhead, centered at the intersection of Peachtree and Roswell roads. In this area can be found the Atlanta History Center, the Governor’s Mansion, the Roxy Theatre, Chastain Park and amphitheater, and Lenox Square (the city’s first mall). Just outside Buckhead and the city limits, along Peachtree Street, is Oglethorpe University.

East

To the east of downtown Atlanta can be found Inman Park (the city’s first planned suburb) and the historic Virginia Highland neighborhood, the Carter Center, Emory University, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Fernbank Museum of Natural History, Agnes Scott College, and East Lake Golf Club (where Bobby Jones learned to play golf). Little Five Points is the center of the alternative arts and music scene and offers theaters, music venues, galleries, restaurants, and nightclubs.

South

The area of Atlanta south of downtown includes Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport; the site of Fort McPherson, which was purchased by the filmmaker Tyler Perry in 2015; and the United States Penitentiary Atlanta, a medium-security federal prison. Atlanta Metropolitan State College is also located south of Atlanta’s downtown. It received state college status in 2011.

West

The west side of Atlanta contains Booker T. Washington High School; Washington Park (a Black residential community built in the 1920s and containing the first public park, tennis courts, and swimming pool for African Americans in Atlanta); Hammonds House Galleries; and the Wren’s Nest (home of writer Joel Chandler Harris).