One of the most valuable sources available for understanding the experiences of enslaved people in the American South is the testimony that they themselves produced in a variety of ways, both during and long after the existence of the “peculiar institution.”

These testimonials, generally referred to as slave narratives, include memoirs and autobiographies written by fugitives from slavery who fled to the North and were assisted by abolitionists with the publication of their stories, as well as twentieth-century oral interviews with elderly freedpeople that recorded their memories of life during slavery and the circumstances of their emancipation either during or after the Civil War (1861-65).

Narratives of Fugitives from Slavery

A number of autobiographies written by African Americans who escaped slavery were published in the first half of the nineteenth century, part of a large body of abolitionist literature intended to make clear to all readers the cruelty and immorality of slavery. Those published in the 1840s and 1850s helped fuel northern opposition to slavery and intensified the sectional crisis that would lead to the breakdown of the Union in 1861. The majority of these narratives were from enslaved laborers who escaped from the southern border states; Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky figure prominently in the most widely read of these works, by Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, and Solomon Northup.

Those enslaved in the Deep South had far less opportunity and faced far greater risk in attempting to escape to the North, and thus there are fewer narratives from that region. Nevertheless, three of the most significant such narratives come from Georgia. John Brown, though born in Virginia, spent much of his youth and early adulthood enslaved by Thomas Stevens, who moved Brown from Milledgeville to Decatur, before he escaped in the mid-1840s. Stevens’s cruelties to Brown, along with those of Stevens’s son, who inherited him, are laid out in full in Brown’s Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Now in England, written and published in England in 1855.

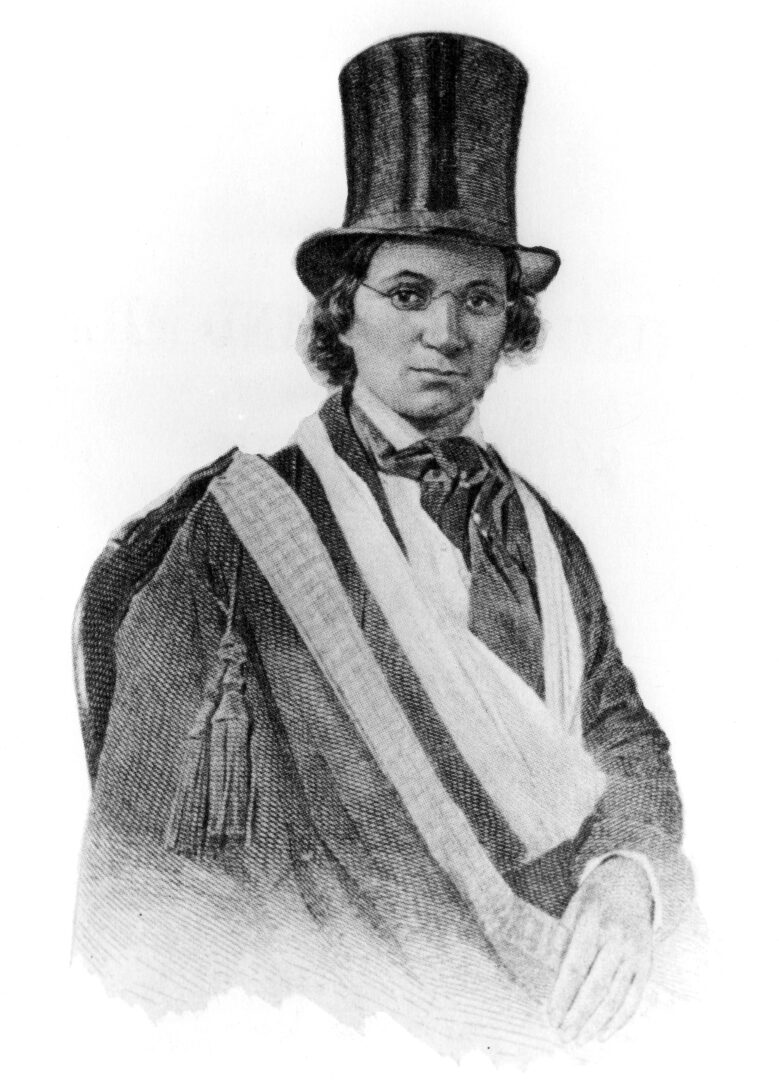

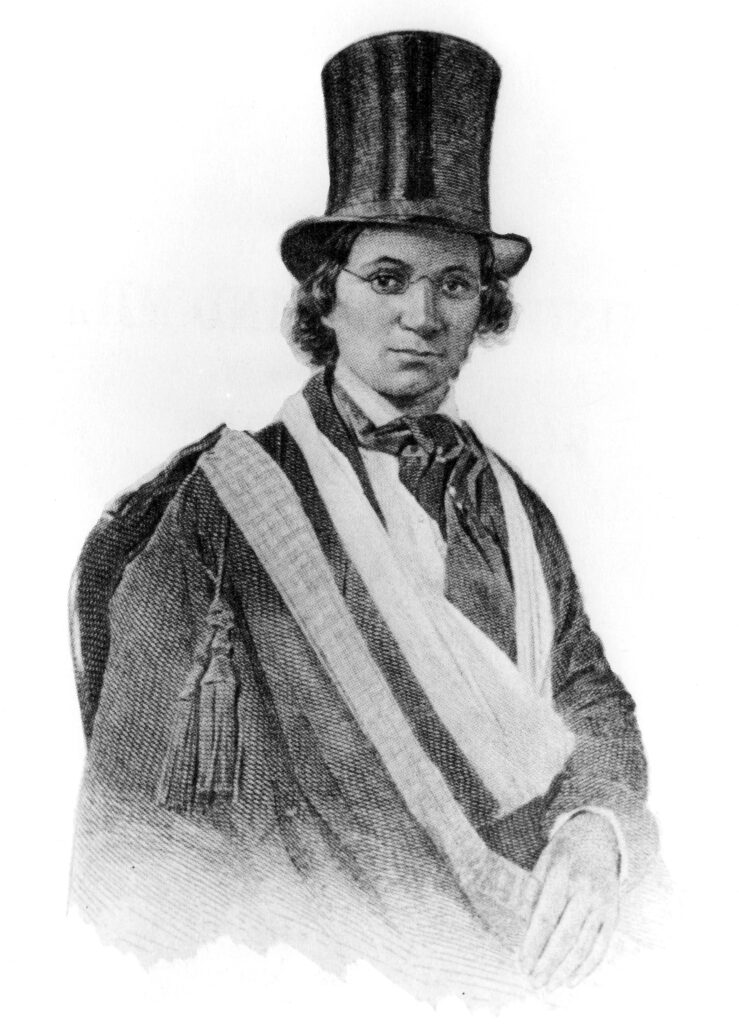

Even more sensational was the narrative of William and Ellen Craft, who escaped by train from Macon and then steamship from Savannah. The fact that they were husband and wife, that Ellen disguised herself as a white man, and that the journey northward was so harrowing made their book, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom: The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (1860), particularly popular. It has enjoyed a recent resurgence of interest and was reprinted in new editions in 1999 and 2000.

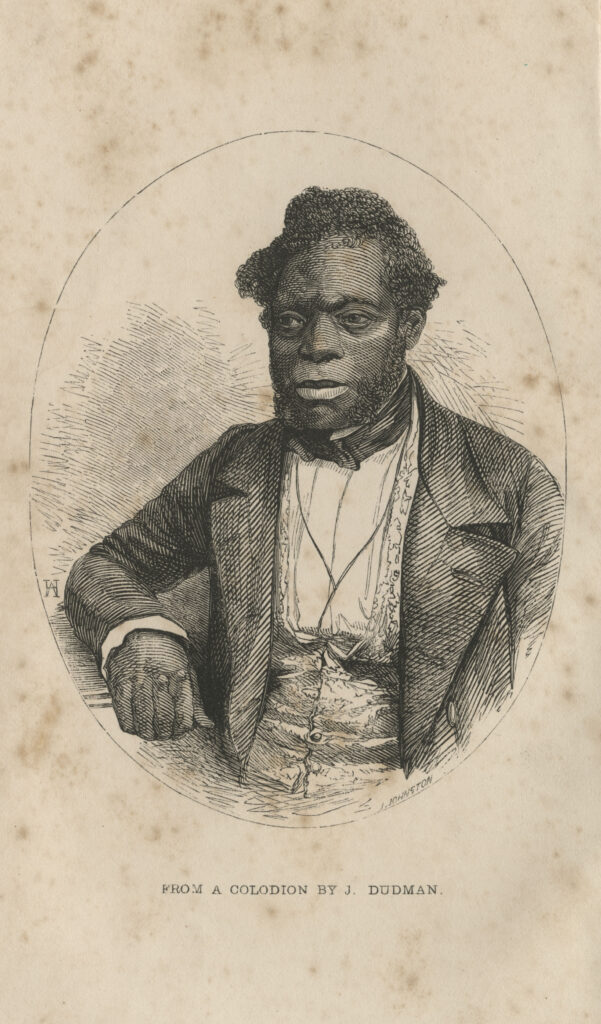

In his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789), Olaudah Equiano recounts his early childhood in Africa, his capture by slave traders, his experiences in Savannah, and the purchase of his freedom. Born in an inland village in present-day Nigeria, Equiano was sold at age eleven to a Royal Navy lieutenant who pressed the young man into naval service in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). (Some scholars, notably Vincent Carretta, have questioned the authenticity of this part of his story, citing evidence for a South Carolina birthplace; the issue is not settled.) After being purchased by a succession of owners, Equiano was brought to Savannah, where he plied the Savannah River as a trader, earning wages for both his enslaver and himself. Equiano purchased his freedom in 1766, whereupon he continued to work as a mariner, traveling widely before settling in London, England, where he published his narrative.

Interviews with Freedpeople

After the Civil War, interest in the lives of African Americans faded, but in the late 1920s, anthropologists and sociologists at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee; Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Prairie View State College in Prairie View, Texas, began to collect life histories of freedpeople. Reasons for the scholarly attention included a renewed interest in African American culture; a desire to refute the “plantation myth” of historians like Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, whose book American Negro Slavery (1918) offered readers a rosy and comforting portrayal of benevolent enslavers and happy enslaved laborers; and researchers’ realization that the last generation of people born into slave status was dying.

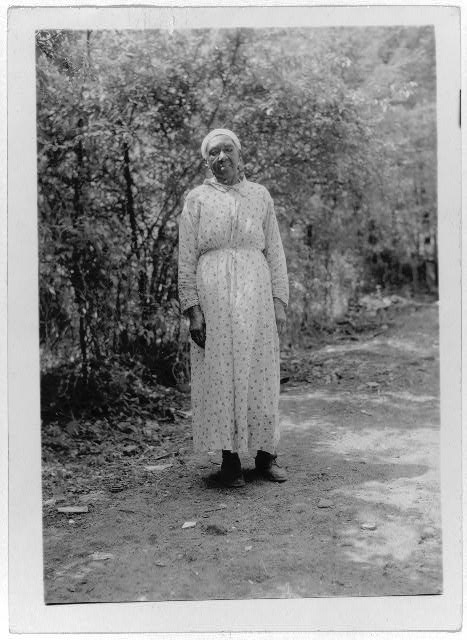

From 1937 to 1939 the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) collected interviews with African American men and women who had been born into slave status. More than 2,000 interviews were collected throughout the southern states, approximately 2 percent of the total population of freedpeople. Almost 200 narratives were collected in Georgia. Although the usefulness of the interviews is debated by historians, they remain an important and compelling resource for the study of slavery.

The FWP was created in 1935 by the Works Progress Administration (later Work Projects Administration), one of the New Deal agencies of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, to provide jobs for white-collar workers during the Great Depression. In addition to writing the American Guide Series, guidebooks to every state and some major cities, the FWP was charged with collecting the life histories of ordinary citizens. John Lomax, a pioneer in the collection of folklore, led the project at its headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Some FWP units, including Georgia’s, began interviewing small numbers of freedpeople, and in 1936 the Georgia Writers’ Project collected more than 100 interviews. It was not until Lomax and other FWP administrators heard the interviews collected by members of an African American unit of the Florida Writers’ Project that they were convinced of the value of preserving these stories. In 1937 instructions were sent to each of the southern and border states directing FWP offices to begin interviewing freedpeople.

Lomax insisted that the interviews were to be objective, verbatim recordings of the experience of each emancipated person encountered by the FWP writers, but in practice the interviews reflect the systematic racism of the Jim Crow South. The early Georgia interviews indicated that interview subjects were more likely to be open and direct with interviewers of their own race. The majority of interviewers were white, however, and Blacks remained underrepresented in all the state writers’ projects. The Georgia Writers’ Project employed the highest number (though not the highest percentage) of African Americans, four of thirty-four interviewers.

The attitude of the interviewer toward the subject, as well as the form of the interview, undermines the reliability of the text for modern readers. Many interviewers, though not all, describe their subjects in terms common for their place and time, such as “old darky” and “typical old Negro mammy.” The instructions to FWP interviewers from Washington asked that the dialect of the subjects be taken down verbatim, and also included a list of recommended interview questions covering ghost stories and a laundry list of superstitions, leaving the subject obscured behind the mask of vulgar stereotype.

The interviews also reflect the attitude of the subject toward the interviewer. Again and again the interviews describe the extreme poverty of many of the subjects, most over the age of eighty, dependent on children, grandchildren, or government relief. Under such circumstances, it is conceivable that a Black subject might be wary or fearful of telling a white person from a government agency anything he or she would not want to hear; in many cases the interviewer seems happy to record the subject confirming the stereotype of the benevolent enslaver and expressing regret for the disappeared good old days of slavery. Whippings and other cruelties are often attributed to the enslaver of a neighboring plantation, not the subject’s own.

Once collected, the interviews were edited by supervisors in charge of the state writers’ program offices, making up for the deficiencies of inexperienced or untrained interviewers and creating a tidy, more “literary” manuscript. In some states, the most shocking allegations of interview subjects were mitigated or removed; interviews from Georgia show less evidence of this practice.

But even discounting the prejudices of the interviewers, and making allowances for the subjects’ inability to be candid, the narratives contribute greatly to the understanding of the lives of African Americans before and during the Civil War. Unlike the antebellum slave narratives, the WPA interviews cover a wide spectrum of people who suffered under slavery. Most subjects were under the age of fifteen when the Civil War ended, but they lived in seventeen states; hailed from cities and from the country, from small farms and large plantations; and worked in a number of tasks. Descriptions of clothing, food, living arrangements, family, and other aspects of daily life can all be found in the narratives.

The most vivid memories of many freedpeople had to do with the war years and the circumstances that led to slavery’s destruction and their own liberation. Georgians frequently recounted episodes involving Sherman’s troops and the upheaval they brought to their plantations and the surrounding neighborhoods. Others recalled their experiences as refugees or fugitives, who left their homes and sometimes their families when presented with opportunities to do so. As freedmen and freedwomen during Reconstruction, many interviewees recalled their early efforts to establish themselves on farms of their own, to gain employment in towns and cities, or to learn to read and write. Confrontations with Ku Klux Klan members often stood out as particularly strong memories for many of those interviewed.

It must also be remembered that each interview is the story of one individual and must be considered individually; it would be a mistake to dismiss the narratives on any set of generalizations. Even stories that are obscured by transcribed dialect, like Janie Satterwhite’s, come through clearly: “Yes’m my Mama died in slavery, and I wuz sold when I was a little tot…. I say to Mama and Papa, 'Good-bye, I’ll be back in de mawnin’—and dey feel sorry fer me and say 'She don’ know whut happenin’.'”

Drums and Shadows

In 1940 the Savannah unit of the WPA published Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, a series of narratives based on more than 100 interviews with freedpeople along the Georgia coast. By highlighting the cultural inheritance of the region’s Black coastal residents, the authors fashioned a pioneering work of scholarship that offers a rich portrait of the region’s folkways. The region’s distinctive Creole language is preserved in lengthy quotations, which were given a literary adaptation and interspersed throughout the text. The book is organized by community and includes a compelling photographic essay by Savannah natives Malcolm Bell Jr. and Muriel Bell.

Although scholars today recognize Drums and Shadows as a pathbreaking work, critics at the time of its publication were less charitable. Perhaps because it emphasized African survivals rather than Black acculturation, as was more common at the time, Drums and Shadows attracted little critical interest and sales were modest. The authors’ decision to highlight African survivals aroused the ire of officials at the WPA’s national office, who alleged that the work promoted a racist theory of cultural evolution, in which vestiges of “primitive” cultures might remain amid civilized culture but would ultimately disappear upon prolonged contact with “advanced” cultures. At the same time, the position of the authors placed them at odds with celebrated scholars of the day, including historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, sociologist Robert E. Park, and anthropologist Franz Boaz, who held that the experience of slavery had erased most, if not all, African influences.

By breaking ranks with the prevailing scholarly consensus and concentrating on African survivals, however, the authors anticipated future turns in multiple fields of scholarship. Their decision to compile survivals in an appendix and forgo analysis altogether was similarly fortuitous, as it ensured that the book would remain relevant well after contemporary theoretical models expired. Most important, Drums and Shadows recorded for posterity examples of folklore, speech, naming patterns, and material culture that have since perished.

Publications

The effort to collect narratives by freedpeople ended in 1939, and each state’s office sent its manuscripts to Washington when the FWP was disbanded. The manuscripts became part of the collections of the Library of Congress in 1941. The Library of Congress made the narratives available on microfilm, but other than small collections such as Drums and Shadows (1940) and Benjamin A. Botkin’s Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery (1945), few of the interviews were available in print until 1972, when George P. Rawick edited the multivolume The American Slave: A Composite Biography, a collection of interviews held by the Library of Congress. The anthology is organized by state, and volumes 12 and 13 contain interviews from Georgia. The publication of The American Slave encouraged the discovery of additional slave narratives held in state collections, which were published in a supplement in 1977. Volumes 3 and 4 of the supplemental anthology contain Georgia materials. Two years later, Rawick published a second supplemental collection, which also included narratives from Georgia.

The Library of Congress has made the complete set of narratives available online as part of the American Memory Project, in the Born in Slavery collection. A small set of audio recordings of interviews with freedpeople, including two subjects from St. Simons Island, is also available online through the American Memory Project.