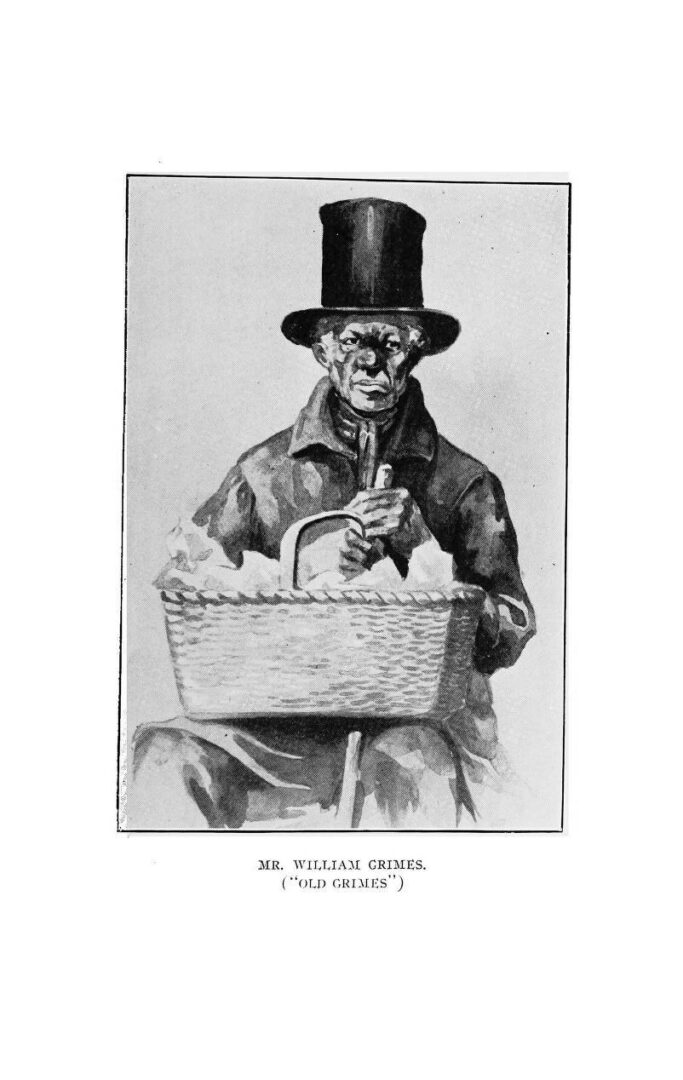

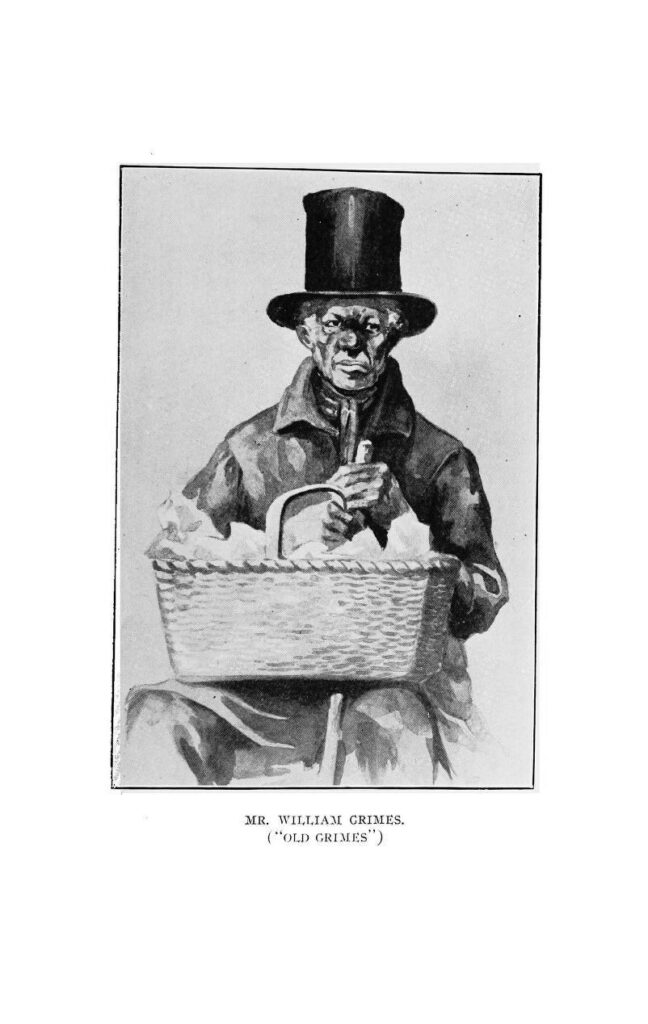

William Grimes, a former enslaved person who attained property ownership and social respectability yet died in poverty, published the first known slave narrative printed in the United States and not England.

Years in Slavery

Born into slave status at King George County, Virginia, in 1784, Grimes spent the first third of his life in that state. As the son of a white man, a planter named Benjamin Grymes Jr., and an enslaved African American woman, he could pass as a white person. He was sold at age ten by his enslaver, William Gibbons Stuart, to William Thornton of Montpelier Plantation in Culpepper County, Virginia. Separated from his mother by this sale, Grimes saw her but once more before her death. By 1811, when he was about twenty-seven years old, he had been acquired and sold by three more enslavers: Mr. Thornton’s son George, P. Thornton (George’s brother), and a man Grimes remembered only as Mr. A—, who took him to Savannah.

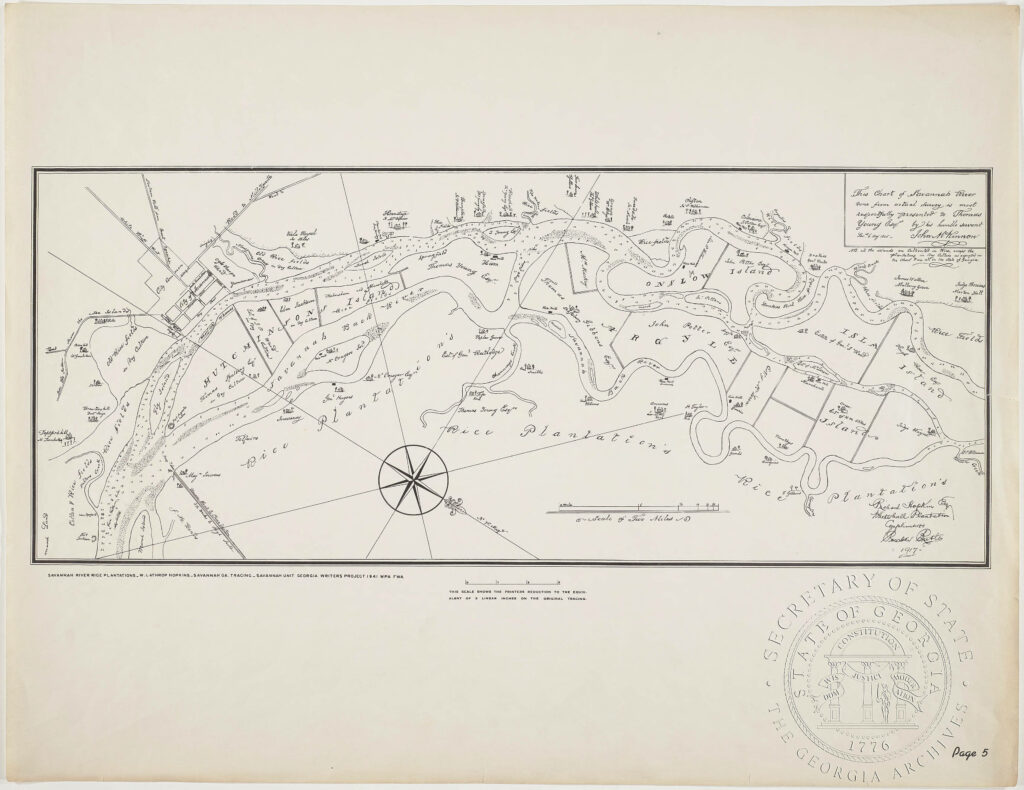

Georgia outlawed the importation of enslaved laborers in 1798, but slavery remained integral to Savannah’s economy. Between 1811 and 1815, Grimes served six consecutive enslavers there. He was hired out or leased from one man, Oliver Sturges, a cotton trader and steamship entrepreneur, to another, Phillip David Woolhopter, who cofounded and edited the Columbian Museum & Savannah Advertiser. This exposure to nineteenth-century Georgia newspapers during his late twenties and early thirties may have served Grimes decades later when he published his memoir. Other Savannah residents enslaved Grimes as well—including the physician Lemuel Kollock, Archibald Stobo Bullock, and Mr. White—until his final sale to Francis Harvey Welman, a merchant.

Nominal Freedom in New England

In 1815 in Savannah, Grimes stowed away among cotton bales in the hold of the brig Casket, based in Boston, Massachusetts. During slavery, Grimes had been owned by ten different enslavers, and both plantation owners and overseers had often subjected him to severe cruelty, which formed physical and emotional scars. Successfully escaping to New York on the Casket, Grimes eventually settled in Connecticut and gradually opened a more pleasant chapter of his life. He was employed successively as a stableman, caretaker, farmhand, and barber, and he demonstrated a formidable work ethic. He purchased property, earned a reputation as a respectable businessman, and settled with his family in New Haven, where he developed a thriving trade as a barber and furniture merchant on Main Street.

Like the fugitives from slavery William and Ellen Craft, who escaped from Macon, Georgia, in 1848, Grimes’s success in Connecticut was overshadowed by the omnipresent fear of detection and restitution to bondage by southern slaveholders, and he actually did encounter two former enslavers. Francis Welman, his final enslaver, sent Grimes an ultimatum from Savannah: Either pay for your freedom or return in chains to Georgia. In 1824, to avoid reenslavement, Grimes purchased his liberty for $500 with everything he owned, plunging himself; his wife, Clarissa; and their children into destitution and homelessness.

Publication of Memoir

The year 1825 marked the New York City publication of the Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave. As the first slave narrative published after the United States became a nation, the memoir is celebrated today as the first of the American slave narratives. By 1855, when Grimes republished Life in New Haven, he had lived there for more than thirty years. An additional conclusion in this second edition chronicles his travels throughout Connecticut in towns such as Bridgeport, Stratford, Norwalk, and Fairfield, where he unsuccessfully attempted to rebuild his wealth.

Elements of the Slave Narrative Genre

According to the scholar William L. Andrews, Grimes’s memoir helped establish stock elements of the genre. These include the narrator’s use of an authenticating subtitle, sketchy details about the narrator’s childhood and parentage, and like the narrative written by the celebrated slave Olaudah Equiano in Georgia, descriptions of physical torture and abuse, starvation and filth, and other examples of slavery’s dehumanizing effects on both the enslaved and their oppressors.

Skilled Labor

Grimes’s two accounts, each books of fewer than 100 pages, were written to recoup the money and regain the status he had lost. Both offer insight into how the labors of enslaved men and women in and around urban areas could facilitate their freedom. Like most fugitives’ narratives, they sparingly disclose details about Grimes’s acquisition of liberty, literacy, and money. As a carriage driver for various enslavers, for example, Grimes achieved a degree of mobility that very likely offered opportunities to learn how to read and write and to gather information about escape routes and facilitators.

He was occasionally hired out to work at other households and plantations, and he was permitted to retain a portion of his earnings. He also peddled firewood bundles and sold rice, the staple crop of Georgia’s lowcountry, which he grew on his own plot. These strategies enabled him to save money for life in freedom, and they anticipated the independence and entrepreneurialism that facilitated his business solvency in the North. Narratives published by John Brown (1855) and the Crafts (1860) include similar examples in which labor, including the skilled work of enslaved antebellum artisans, contributed to both the process of escape and the project of surviving freedom.

Racial Passing

Grimes’s racial passing also anticipates popular plot elements in the slave narrative genre. He passed as a white gentleman in order to walk the city streets at night while evading detection by such slave patrols as the Savannah Watch, composed of white men appointed to find and arrest unattended enslaved persons who might revolt or escape. As he prepared to run away on the Casket, Grimes purchased food and other essentials along the port of Savannah while incognito as a slaveholder accompanied by his servant (actually, a free black sailor). In the North, he reprised his performances as a white man to secure lodging in places that did not serve black people.

Never to regain the social prominence and economic security he once had achieved in freedom, Grimes sold lottery tickets in the final years of his life. The cause of his death in 1865 is unknown. He is buried next to his wife in New Haven.