Thomas Brewer, an African American physician, spearheaded the drive for racial equality in Columbus from the 1920s until his assassination on February 18, 1956, which was widely believed to have resulted from his political activism. Brewer, whose death had considerable impact on local race relations, is recognized as a martyr of the national civil rights movement.

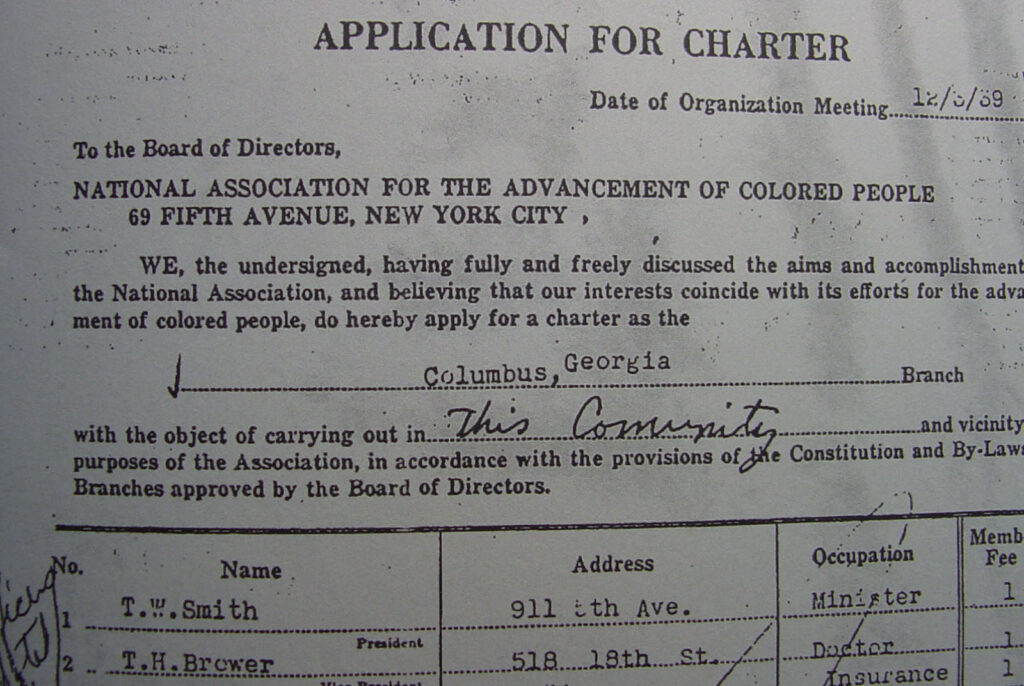

Thomas Hency Brewer was born in Saco, Alabama, on November 16, 1894. He graduated from high school and college in Selma, Alabama, and earned his medical degree from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. In 1920 he joined a thriving Black medical community in Columbus, Georgia, establishing his office on the 1000 block of First Avenue as other Black doctors and dentists had done before him. In 1929 he and other Black professional men created a service organization, the Social-Civic-25 Club; in 1939 Brewer led these same men in founding a chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Columbus.

As the tactician for the local NAACP, Brewer orchestrated the attack on the all-white primary system in the state of Georgia, designating Primus E. King, a Columbus barber and minister, to challenge the system by attempting to vote in the primary election at the courthouse in Muscogee County on July 4, 1944. A generous donor himself, Brewer raised the funds for the subsequent Primus King legal case (King v. Chapman et al.), in which federal courts found in favor of King in 1945 and 1946. Following this victory Brewer initiated successful Black-voter-registration drives in Columbus in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He also campaigned successfully for the hiring of Black police officers in Columbus; four were hired in 1951 to patrol the downtown Black neighborhoods.

Courtesy of Columbus State University Archives

By the late 1940s Brewer was receiving death threats from such hate groups as the Ku Klux Klan. However, it was his support for racial integration of the public schools following the Brown v. Board of Education decision in May 1954 that brought him the opprobrium of more moderate white leaders and organizations. Even before the announcement of the Brown decision, Brewer’s requests to the all-white Muscogee County School Board for more equitable funding of the Black schools had been routinely shelved.

In 1955 two other issues raised local hostility to Brewer: his effort to integrate the golf course on Columbus’s South Commons, and the allegation, which he steadfastly denied, that as a prominent Georgia Republican with national party connections he had used his influence to deny a popular white Columbus citizen the position of city postmaster, a federal government job. Racial tensions were also mounting late in 1955 as a result of publicity surrounding the bus boycott being carried out by the local chapter of the NAACP in Montgomery, Alabama.

Brewer was shot and killed in the midst of this hostility. Luico Flowers, who owned a clothing store beneath Brewer’s office, said he shot Brewer in self-defense when Brewer, after a heated disagreement, entered his store and reached for a pistol. Police and a grand jury accepted Flowers’s story. Brewer and Flowers had witnessed from their places of business the forceful arrest of a Black man by police. Brewer believed he saw a case of police brutality and wanted Flowers to witness accordingly, but Flowers disagreed, believing the man apprehended was resisting arrest. Feeling he had been threatened, Flowers called for police protection. An officer and two other men were in the store at the time of the shooting.

Those who believe the shooting was murder reason that Brewer would never have walked past two white police officers and pulled a gun on Flowers. (Police did find an unfired pistol in Brewer’s left pants pocket; given the frequency of death threats against him, he had long carried it.) Almost exactly a year after Brewer’s death, Flowers was found dead from a gunshot wound to the head. His death was officially ruled a suicide. For many, Flowers’s death was evidence of a cover-up of Brewer’s murder.

The death of Brewer, affectionately known as “Chief” by his associates, shocked the Columbus Black community. An estimated 2,500 mourners flowed out of First African Baptist Church onto Fifth Avenue for his funeral service. Brewer’s widow, Lillian; their daughter, Thelma; and her husband, Dr. R. M. Haskins, left the city. (Brewer’s son, Thomas H. Brewer Jr., also a doctor, had left the city years before.) Brewer’s attorney, Stanley P. Hebert, moved his family out of town, as did Dr. W. G. McCoo and his wife, Mary, also a physician. (One of the McCoos’ children, Marilyn, would later become a nationally known rhythm-and-blues singer.)

E. E. Farley, a Columbus realtor, stayed on as president of the local NAACP but succumbed to a heart attack in late 1956. As a result of the Brewer shooting, the Columbus civil rights movement, although ultimately effective, followed a less confrontational course of action than movements in other Georgia cities in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Brewer is buried in Green Acres Cemetery in Columbus.