On the morning of July 4, 1944, Primus E. King, an African American duly registered to vote in Georgia, sought to cast a ballot at the Muscogee County Courthouse in Columbus in the Democratic Party’s primary election. Shortly after entering the courthouse, King was roughly turned away by a law officer who escorted him back out to the street. During this time the Democratic Party monopolized political activity in Georgia, as in other southern states, and the party’s primary provided the only occasion in which a voter was offered a choice between candidates seeking offices in state and local government. For this very reason Blacks were denied participation in the primaries by the Georgia Democratic Party and its county affiliates.

King’s challenge to the white primary had been planned by a group of Columbus African American civil rights activists led by Dr. Thomas Brewer. By prearrangement King, after his rejection, walked several blocks to the office of Oscar D. Smith Sr., a white attorney, who prepared a lawsuit against members of the Muscogee County Democratic Party Executive Committee, chaired by Joseph E. Chapman, for denying King his right, as a citizen of the United States, to vote. In September 1945 the arguments in

On October 12, 1945, Federal Judge T. Hoyt Davis ruled in King’s favor and awarded him $100 at 7 percent interest, since it was clear that the defense attorneys would appeal the decision. Because the U.S. Supreme Court had recently declared Texas’s whites-only primary unconstitutional on the grounds that the Texas Democratic Party was part of the state government, the defense had argued that the Democratic Party in Georgia was a private entity.

On March 6, 1946, in the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, Louisiana, Judge Samuel H. Sibley, a Georgia native, denied the contention of the defense in King v. Chapman, arguing that Georgia’s election laws “associated” the state with the Democratic Party primary and that the state, therefore, “puts its power behind the rules of the party.” (Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer who later orchestrated the famed school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, served as amicus curiae for King before the appeals court.)

The Muscogee County Democratic Party refused to let the case drop. Chapman’s attorneys then requested that the U.S. Supreme Court review and overturn Sibley’s decision. The high court declined to hear the case on April 1, 1946. In March 1945 the state of Georgia had abolished the three-dollar poll tax, thereby removing the economic impediment to voting in the state. Primus King’s almost two-year-long struggle against the white primary, paid for by more than $10,000 dollars raised by Brewer and others in the Columbus chapter of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), now finally eliminated the legal barriers that had stood in the way of Black Georgians’ right to cast ballots in state and local elections.

King was courageous in his confrontation with law officers on Independence Day 1944, and brave in his determination to pursue the case despite threats made against his life. King was not, however, a political activist. He was born on February 5, 1900, to Lucy and Ed King near Hatchechubbee in Russell County, Alabama, where his father was a sharecropper. King never received any formal education. As a boy, he moved with his family to Columbus, where he worked with his father on a crew building the Meritas cotton mill. In 1921 he married Genie Mae King, who later taught for many years in public schools. The couple had one daughter. In his early twenties King worked as a chauffeur and butler for a prominent white family in Columbus. He suffered humiliation in his work as a servant and encountered discrimination as a customer at white-owned eating establishments; these experiences later played a role in his decision to work with Brewer to demand his right to vote.

As a young man King sought to lessen the pain of discrimination by becoming economically independent. He quickly learned barbering by watching others practice the trade and was able to purchase his own shop with his small savings. After his conversion to Christianity during a revival meeting, he became a pastor at Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church in 1939 and later ministered at Salem Baptist Church. King’s religious faith, he later noted, fortified him for his assault on the white primary. King barbered and ministered long before and after the legal case that put his name in newspapers around the country. He sold the barber shop and retired in 1963. On November 3, 1986, he died in Columbus.

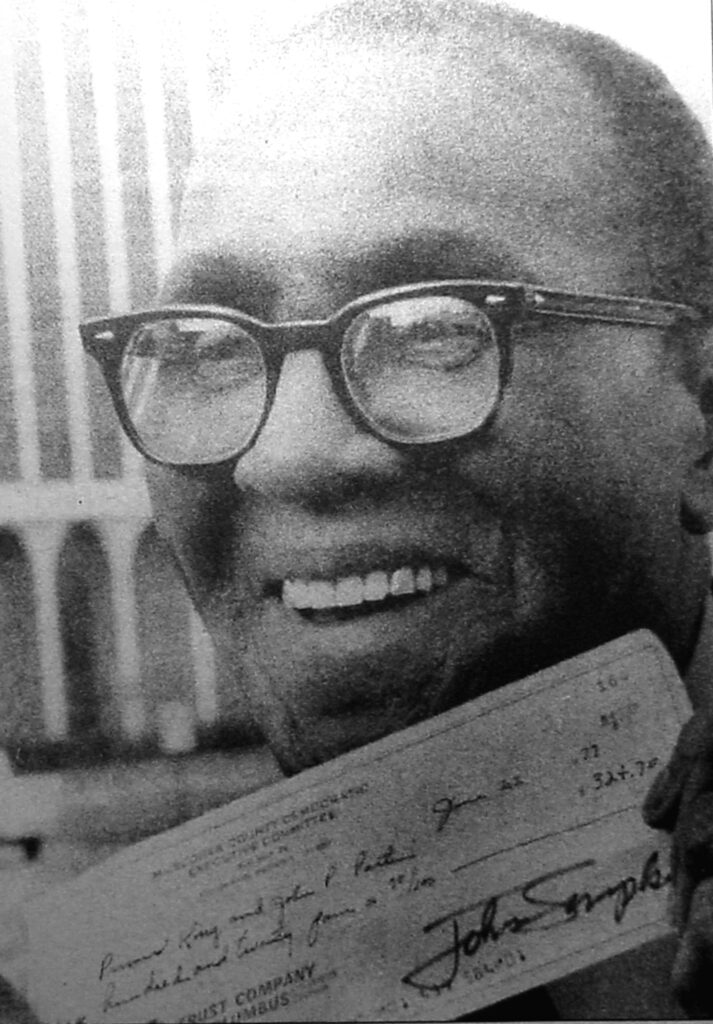

Eventually, honors came to King from the political establishment that had once spurned him. In 1973 Mayor Bob Hydrick proclaimed June 28 as Primus E. King Day in Columbus; in 1977 the Democratic Executive Committee of Muscogee County paid King the $100 plus interest ($324.70) that they owed him; and in 2000 Governor Roy Barnes signed into law a bill naming a stretch of state road in Columbus as the Primus King Highway.