Georgia played a significant role during America’s participation in World War I (1917-18). The state was home to more training camps than any other state and, by the war’s end, it had contributed more than 100,000 men and women to the war effort. Georgia also suffered from the effects of the influenza pandemic, a tragic maritime disaster, local political fights, and wartime homefront restrictions.

War Sentiment in Georgia

As newspaper headlines around the world reported the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28, 1914, Georgia papers paid very little attention to the news. The assassination provoked an immediate response from several European countries, however, all of whom were concerned about the growing political instability and the possible shift in power on the continent. In early August, hardly a month later, war broke out in Europe after Germany attacked Belgium. U.S. president Woodrow Wilson was determined to keep the United States out of the conflict. On August 19 he delivered a speech defining America’s stance on the war. “Every man who really loves America,” he said, “will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned. . . . The United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name.”

Nearly a year later, the torpedoing of the transatlantic liner Lusitania on May 7, 1915, again caused little outcry in Georgia, although voices from the North were quick to call for America’s entry into the war. Hoke Smith, a U.S. senator from Georgia, said that war was not needed to avenge the deaths of a few “rich Americans” who had gone down with the ship. Local newspapers in Savannah and Athens also warned the public against hastily supporting the case for war, which had already hurt the state’s economy. A curtain of Royal Navy ships, forming the British blockade of Europe, prevented Georgia cotton, tobacco, timber, and naval stores from reaching potentially lucrative German and Austrian markets.

The events of the war also contributed in large part to what is known as the Great Migration, during which African Americans moved from the South to urban areas in the North. New war-related jobs suddenly available in northern cities, coupled with the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan and mass lynchings across the South, spurred this flight. The Great Migration reached its peak between 1915 and 1930, by which time Georgia had lost more than 10 percent of its Black population.

The Declaration of War and the Selective Service Act

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, thereby entering World War I. For about two years, Georgia’s newspapers had been writing against the war because of its negative impact on the state’s economy, yet almost overnight the media changed their tune, becoming anti-German and strongly patriotic.

War fervor in Georgia sometimes raged to the immediate detriment of common sense. Soon state newspapers were warning readers to be on the “lookout for German spies.” The loyalty of some Georgians suddenly became suspect: state labor leaders, teachers, farmers, and foreign immigrants were scrutinized for their “patriotism.” Poorer farmers, especially the ones who still professed Populist leanings, were pressured into buying war bonds, signing “Declarations of Loyalty,” and draping American flags over their plows while they worked. The state school superintendent encouraged all students and teachers to take a loyalty oath and to plant and tend what would become known as “liberty gardens”; teachers stopped covering German history, art, and literature for fear of being thought disloyal.

Loyalty pledges and flag-waving aside, President Wilson soon realized that volunteerism alone could not sustain an army capable of defeating Germany, so on May 18, 1917, he approved the Selective Draft Act (popularly known as the Selective Service Act) to remedy the problem. On June 5 all of Georgia’s and the nation’s eligible men, of ages twenty-one to thirty, were required to register for the draft.

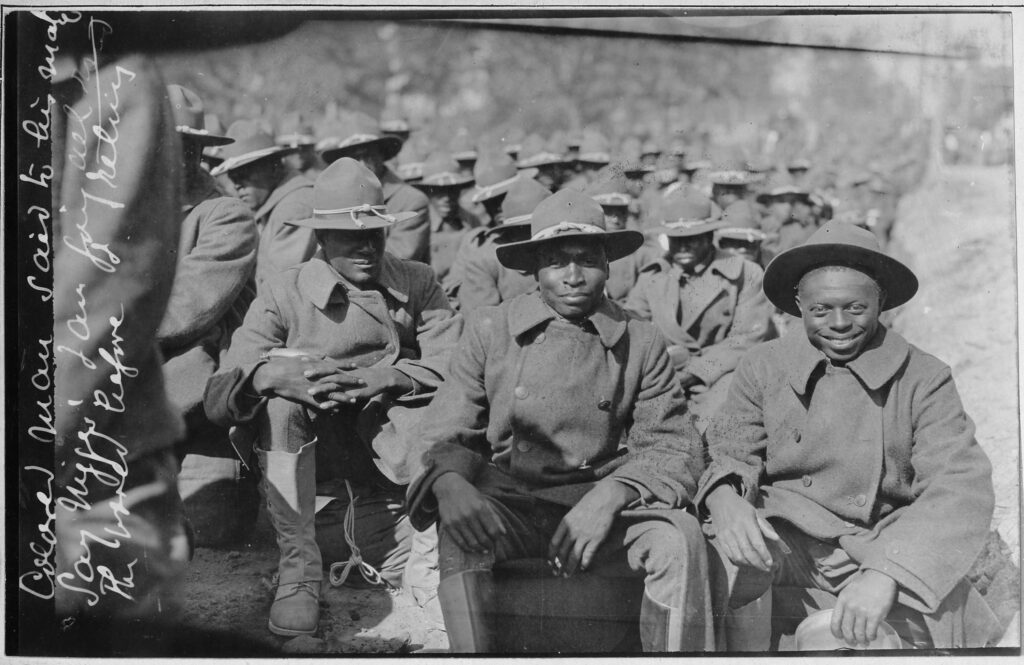

Many white men in Georgia sought to prevent Black men from being drafted. As in the Civil War (1861-65), when some enslavers refused to loan enslaved people to the Confederate government for various kinds of war work, some land-owning whites in 1917 refused to allow their Black sharecroppers to register for the draft or to report for duty once they had been called. Many Black men were arrested and placed in camp stockades for not heeding draft notices that they had never received from landowners. Selective Service officials blamed Georgia’s white planters for many such delinquency issues; for most of the war, local draft boards “resisted sending healthy and hard-working Black males” because they were needed in the cotton fields and by the naval stores industry.

The very idea of conscription was abhorrent to many Georgians, including U.S. senator Thomas Hardwick, Rebecca Latimer Felton, and Thomas E. Watson. Watson even challenged the Selective Draft Act in federal court, when he announced his intentions of defending two Black men who were jailed in Augusta for failing to register for the draft. Donations poured in to help support the case. On August 20, 1917, the trial took place outdoors in order to accommodate the large crowd that came to hear the old Populist’s oratory. In the end the judge upheld the constitutionality of the act, and more than 500,000 men were registered in Georgia.

Federal Installations and War Camps

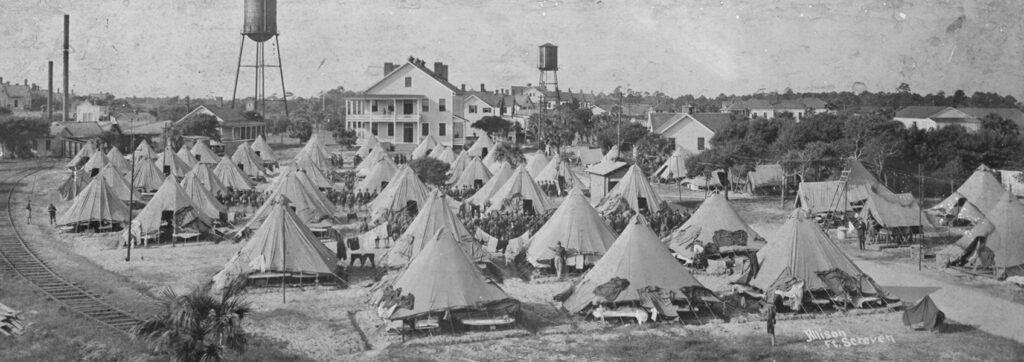

The state had five major federal military installations when the United States entered the war in 1917. The oldest garrison was Fort McPherson, located south of Atlanta, which opened in 1889; the newest was Fort Oglethorpe, constructed near the Tennessee border just a few years after the Spanish-American War in 1898. Fort Screven, a large coastal artillery station on Tybee Island, guarded the entrance to the Savannah River. Augusta housed both the South’s oldest federal arsenal, the Arsenal at Augusta, and the army’s second military airfield, Camp Hancock.

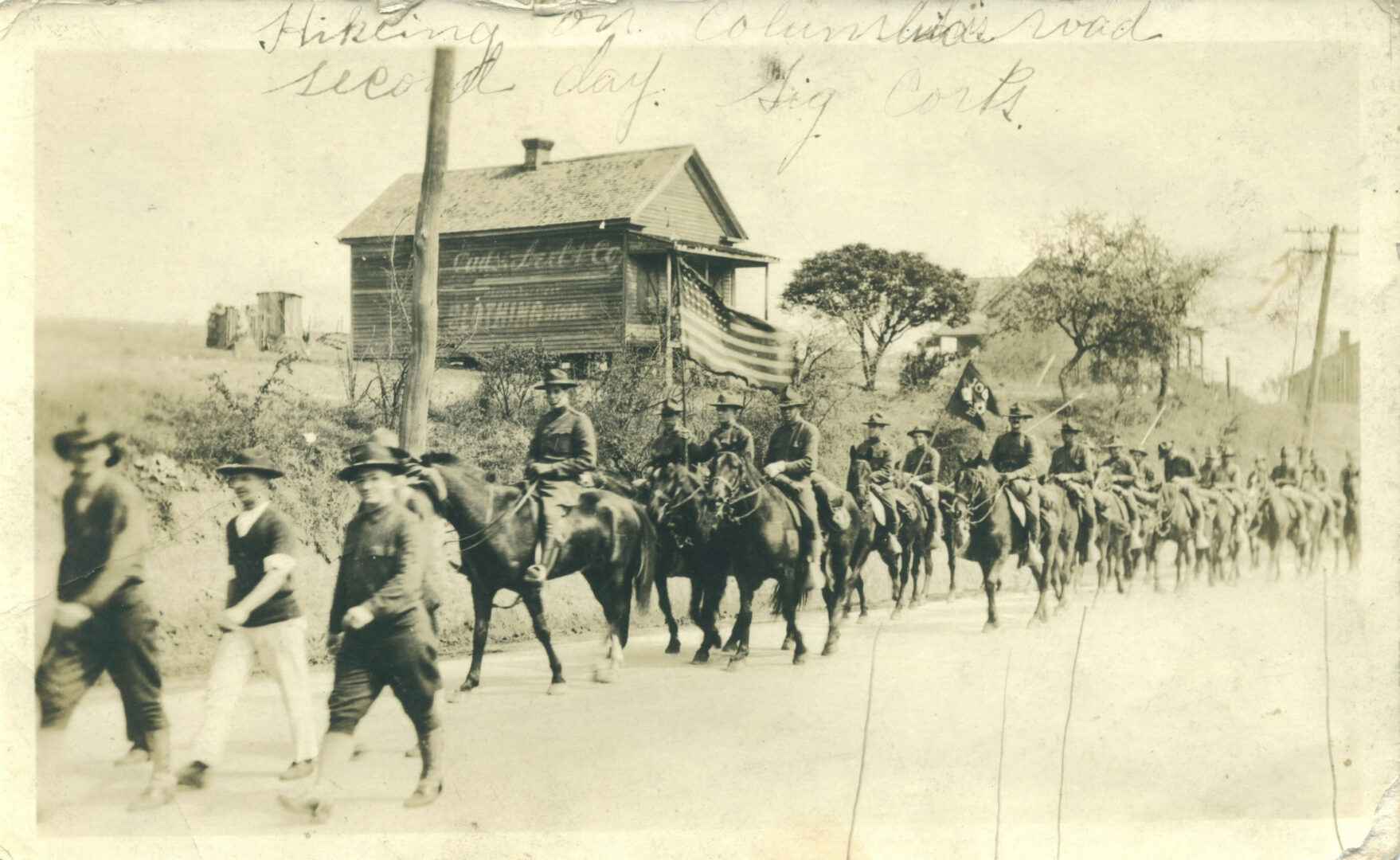

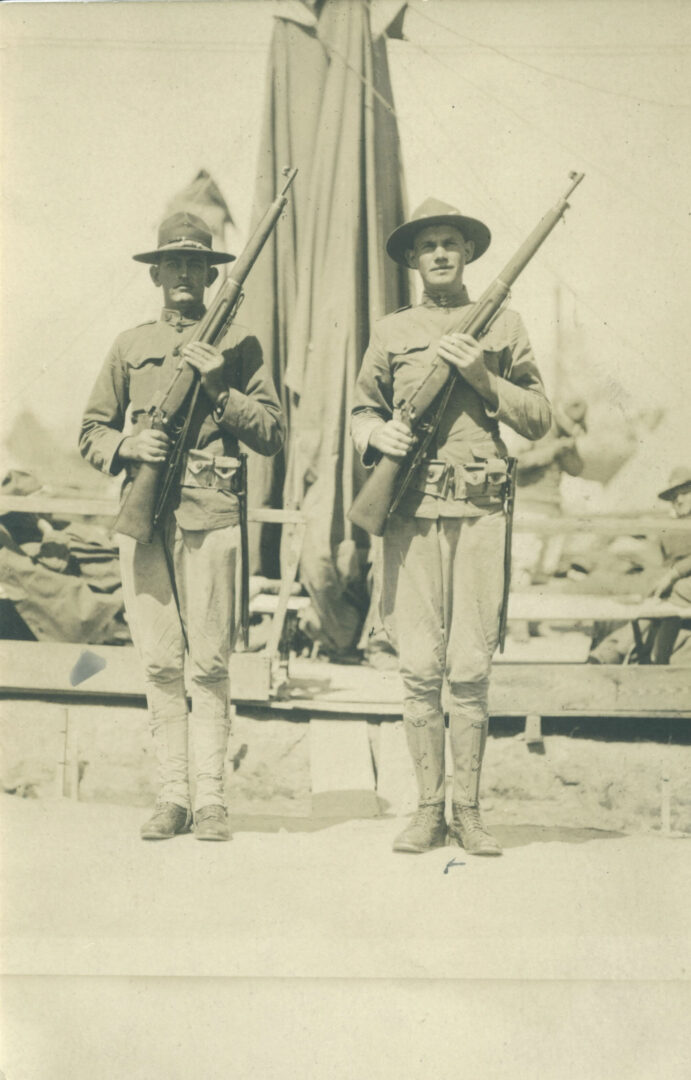

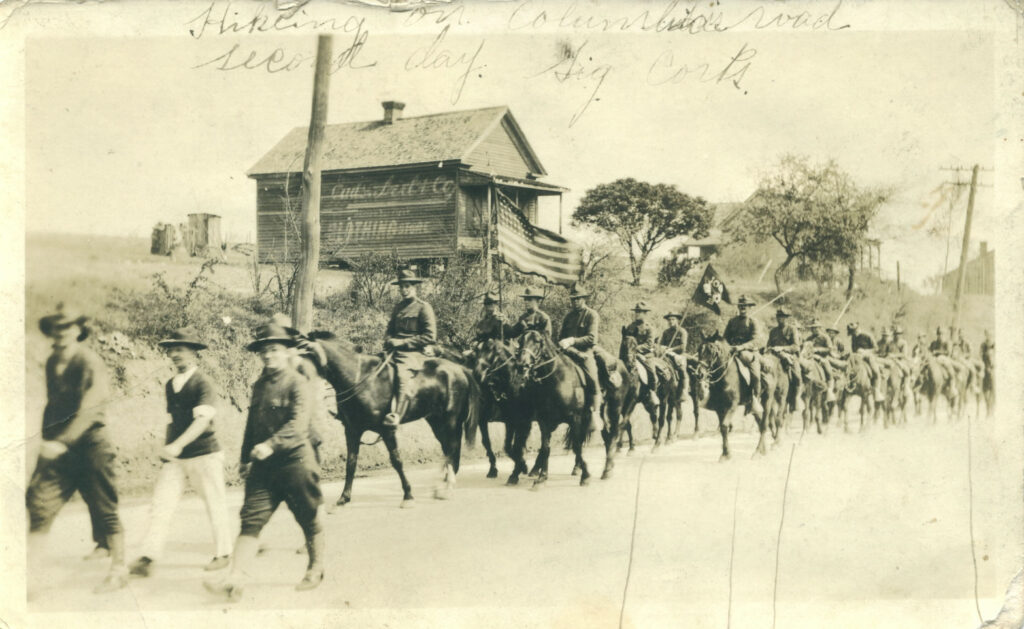

Georgia had many war-training camps as well. The large national army cantonment at Camp Gordon, which opened in July 1917, was located in Chamblee, northeast of Atlanta, and was the training site of the famous Eighty-second All-American Division. The division included men from several different states, but Georgians made up almost half its number. National Guard training camps were based in Augusta and Macon; Augusta’s Camp Hancock was home to the Twenty-eighth Keystone Division, while Camp Wheeler in Macon hosted the Thirty-first Dixie Division, which was entered by almost all of Georgia’s National Guard. Eventually more than 12,000 Georgians were active in the Thirty-first. Specialist camps, such as Camp Greenleaf for military medical staff, Camp Forrest for engineers, and Camp Jesup for Transport Corps troops, were scattered around the state. At Souther Field, located northeast of Americus, a flight school trained almost 2,000 military pilots for combat in the skies over France.

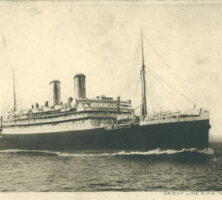

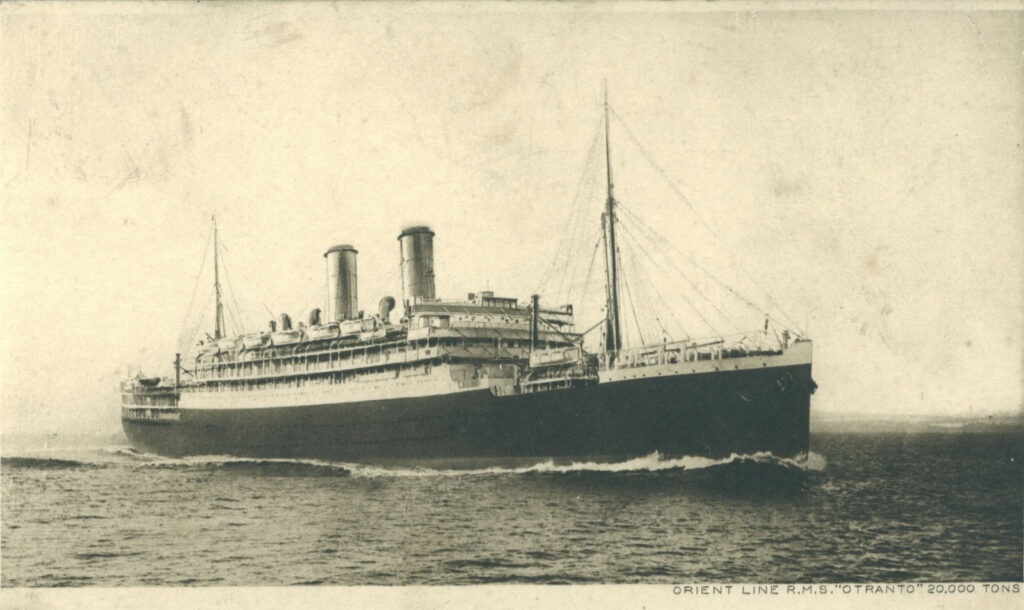

The Otranto Disaster

On the morning of September 25, 1918, about 690 doughboys (infantrymen), mostly Georgians from Fort Screven, boarded the old British liner Otranto, which set sail with a large Allied convoy bound for England. The Otranto was a medium-sized, prewar passenger liner that, like so many others, had been pressed into military service by the British Royal Navy. As the convoy entered the Irish Sea on October 6, still a day from port, a storm developed with gale-force winds. A tremendous wave struck the Kashmir, a converted troopship within the convoy, causing it to break ranks and veer hard. It rammed at full steam into the unsuspecting Otranto and caused severe damage to the liner. With a gaping hole in her side and a loss of power, the Otranto was helpless against the strong, storm-driven current, and she began to drift toward the nearby Scottish island of Islay and its rocky coast. The Otranto began to sink slowly before a huge wave pushed the ship onto Islay’s rocks. The ship broke apart and quickly sank. Approximately 370 men were killed, an estimated 130 of whom were Georgians.

Influenza

In late September 1918, new draftee replacements for the Fort Screven Coast Artillery units began reporting to the infirmary seriously ill. Within a few days, it became clear that the men had contracted the dreaded Spanish flu. On October 1 the number of ill at Augusta’s Camp Hancock jumped from 2 to 716 in just a few hours. The next day, Camp Gordon near Atlanta reported that 138 soldiers had contracted the virus. On October 5 Camp Hancock was quarantined with 3,000 cases of flu, but the quarantine came too late, as 47 cases had already reached the nearby city; by evening, more than 50 soldiers were dead, while many more had contracted pneumonia. Though seriously affected by the Spanish flu epidemic, Georgia escaped the massive numbers of sick and dying counted in other states along the East Coast.

Remembering the War

Though the war would not officially end until belligerent nations signed the Treaty of Versailles the following year, hostilities ceased on November 11, 1918, when an armistice was reached between Germany and the Allied nations. In the months and years that followed, Americans attempted to commemorate the war in a variety of ways, establishing a national holiday to honor those who served, commissioning public statuary, and working to ensure that wounded soldiers would enjoy rehabilitative care. Georgians figured prominently in these efforts.

Americans celebrated the first Armistice Day on November 11, 1919. Congress established the occasion as a national holiday in 1938 and changed the name to “Veterans Day” in 1954 at the urging of veterans organizations.

In Georgia, efforts to honor American servicemen began immediately after the cessation of hostilities. In December 1918 Moina Belle Michael, an administrator and professor at the University of Georgia in Athens, began designing paper poppies to fund the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers. Her efforts attracted national and even international attention, and the sale of poppies would raise millions of dollars for rehabilitative care in the years that followed. Poppies are still sold in Britain for Remembrance Day (Armistice Day), held on the second Sunday in November.

Commemorative efforts that began in southwest Georgia also enjoyed wide influence. The tragic sinking of the HMS Otranto had stunned many Georgia communities, perhaps none more than the small town of Nashville. The seat of sparsely populated and agricultural Berrien County, Nashville lost twenty residents in the Otranto sinking and another twenty-seven young men to combat or disease. At the war’s end, the citizens of Nashville decided to erect a monument honoring the community’s fallen heroes.

Sculptor Ernest M. Viquesney, an Indiana native living in nearby Americus, designed a statue of an American doughboy in combat. The seven-foot-tall bronze soldier stands in bronze mud amid broken stumps and tangles of barbed wire. The town of Nashville paid $5,000 for the public sculpture. The original statue was placed in Nashville in the summer of 1921 and unveiled in 1923, after the city paid for the sculpture in full. On Armistice Day, 1921, Americus hosted a public ceremony to celebrate the unveiling of its doughboy statue, making it the first such work on public display in Georgia.

As word of Viquesney’s statue spread, representatives from other towns visited Americus to see the monument. New orders poured in, and Viquesney went into business, making the statues he now called the Spirit of the American Doughboy. The sculptor would go on to produce more than 150 statues between 1921 and 1943 and deliver them to towns all across the nation.

In 1922 two of America’s war dead received special recognition and a large memorial site in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. These fallen young men represented America’s Unknown and Known Soldiers, comprising the nation’s unknown or missing dead and all of the known troops killed during World War I. Congress chose Rome’s Charles Graves, who had been killed in combat at the age of eighteen and buried with full military honors in France, to be America’s Known Soldier, and plans were made to create a monument and coordinate his reburial in Arlington. Graves’s mother, however, wanted him buried at the family cemetery near Rome. Congress honored the mother’s wishes and sent the body to Georgia. The following year, Graves was buried once again, this time in a more prominent memorial at Rome’s Myrtle Hill Cemetery. Later, three World War I machine guns were placed around the site to “guard” Charles Graves for eternity. The city planted thirty-four magnolia trees around the cemetery to honor each of Floyd County’s lost lives.