Extensive military training activity took place in several camps around Georgia during World War I (1917-18). The state’s most important cantonment, or temporary training camp, was Camp Gordon near Atlanta, where war hero Alvin York of Tennessee trained. Troops from Camp Gordon and Camp Hancock in Augusta also played critical roles in the 1918 Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which delivered the Allied victory that ended the war.

Like all southern military camps, those in Georgia operated under the segregation laws of Jim Crow. Federal prohibitions on Black troops in combat meant that African American recruits trained and served in engineer service or labor battalions under white officers.

War Preparedness Movement

U.S. Army general Leonard Wood, the most articulate advocate of national defense after the 1914 outbreak of war in Europe, had a brief, influential career in Georgia. Stationed in 1893 as an army surgeon at Fort McPherson in Atlanta, Wood played football and was the team’s first coach at the Georgia School of Technology (later Georgia Tech). Before the war began, Wood led a national War Preparedness Movement that trained recruits during his tenure as U.S. Army chief of staff (1910-14). He insisted that recruits could learn most military jobs in six months. Public opinion began to favor the Preparedness movement after Germany’s 1915 sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania.

Commanding the new southeastern department of the army in Charleston, South Carolina, Wood desired to establish cantonments quickly for soldiers in his region. The United States implemented Preparedness in 1917, prior to entering the war. Fort McPherson, the army’s first permanent southeastern installation, served as Georgia’s primary camp for officers. From 1917 to 1919, to help manage an unprecedented mass conscription, officers took three-month courses in commanding army draftees.

Wood required that all cantonments hosting army divisions (comprising about 35,000 troops, including support) be constructed on inexpensive land near large cities, have access by double-tracked railroads for quick movement of men and supplies, and have access to a plentiful water supply. He assigned quartermaster generals to supervise rushed, massive building projects.

Student Army Training Corps in Atlanta

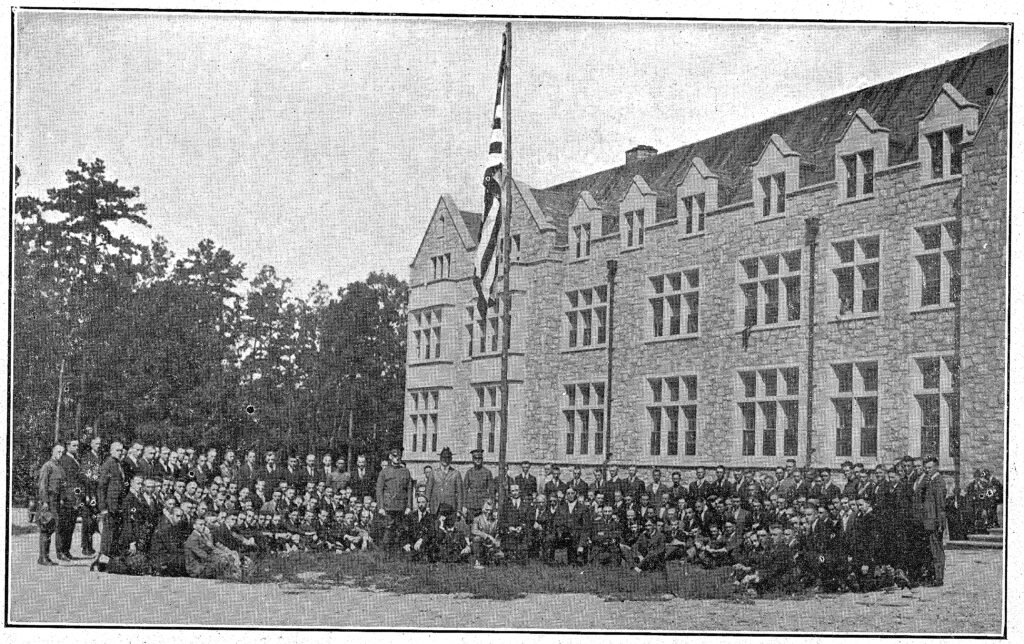

Georgia participated actively in military training for university men in what historian Walter Cooper called “Atlanta’s College Army.” Camp Gordon officers jointly administered the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), the precursor of ROTC, with officials at Oglethorpe University. The program, with a capacity enrollment of 300 cadets, advertised an ideal location near both Atlanta and Camp Gordon.

Other SATC programs with army cosponsorship in Atlanta were at the Atlanta–Southern Dental College, with 225 men, and Emory University, with 250. Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) had 225 Black men enrolled. Georgia Tech had the most participants, about 1,000, in a ground school for pilots and infantry, as well as for Signal Corps training.

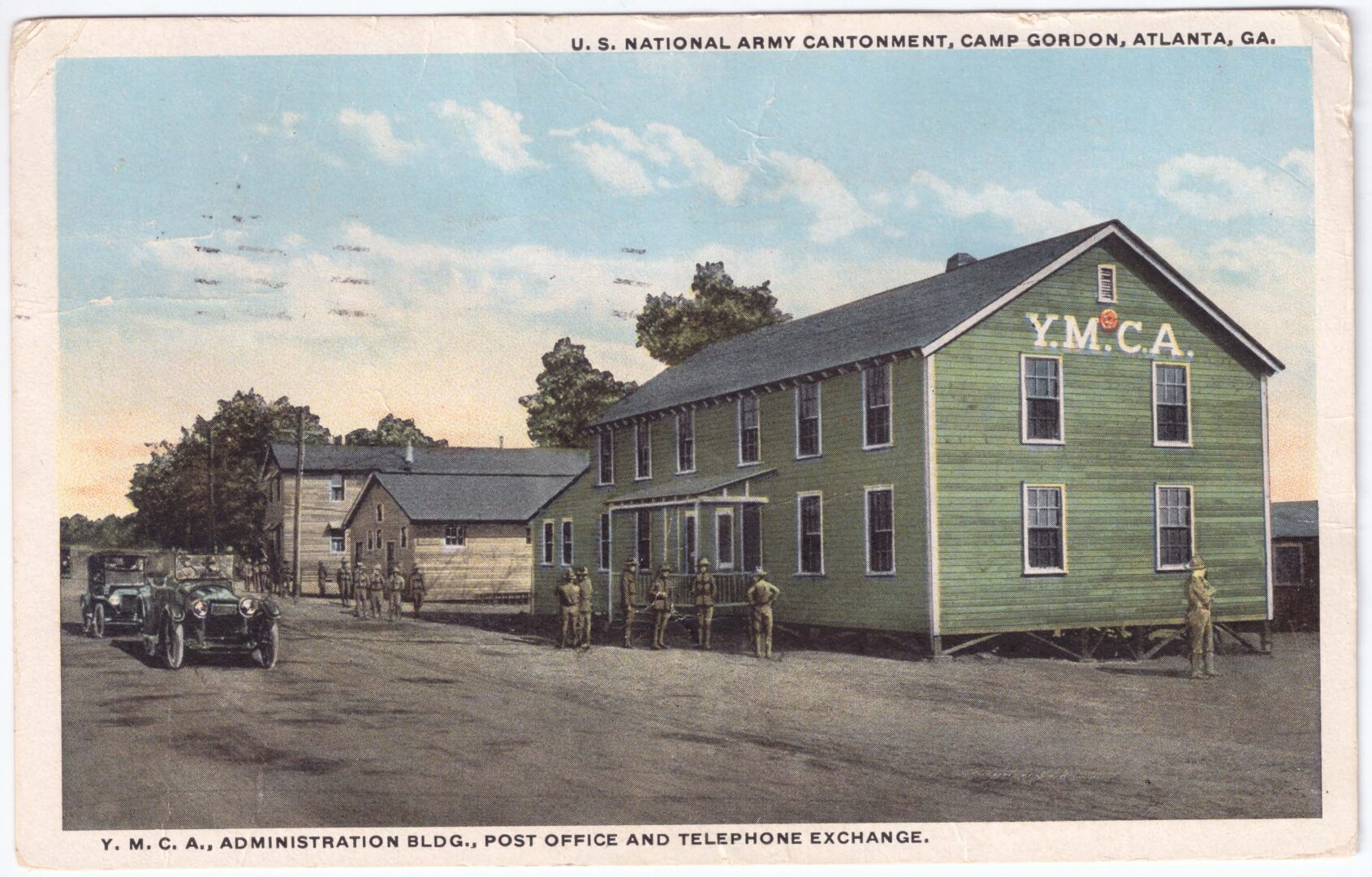

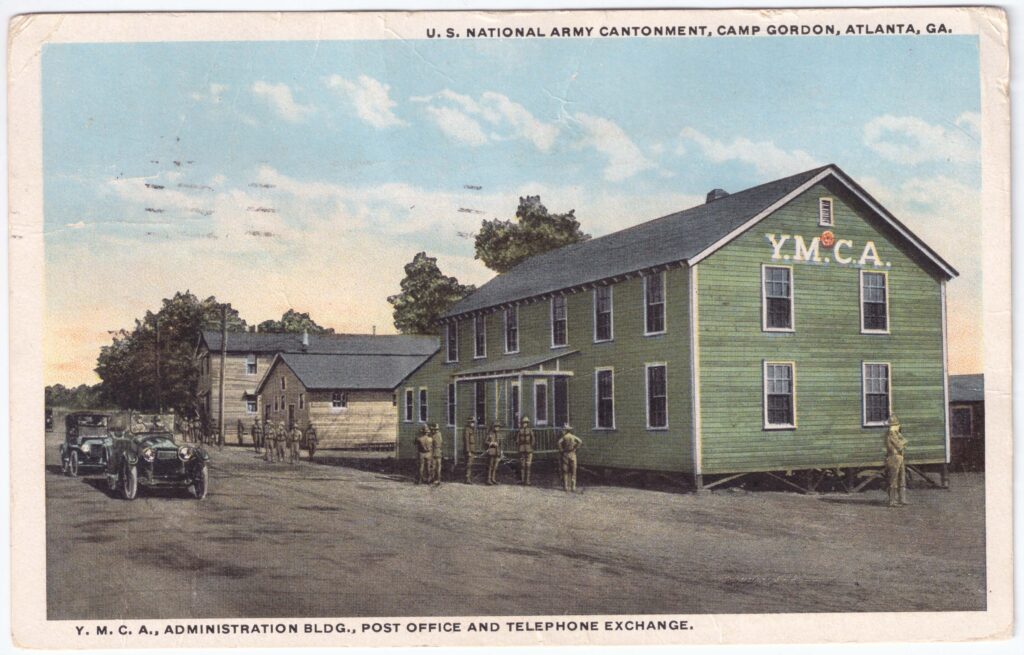

Camp Gordon

Wood, along with Atlanta civic leaders Asa Candler and Ivan Allen Sr., selected the Camp Gordon site in Chamblee, northeast of Atlanta in DeKalb County. Georgians named their premier World War I cantonment, a regular army camp, after John B. Gordon, a Confederate general during the Civil War (1861-65) who later served as governor of Georgia and as a U.S. senator.

The Eighty-second “All American” Division, destined for fame on the war’s Western Front, originated at Camp Gordon, a “war city” with more than 1,600 new wooden buildings and more than 46,000 troops at its height. Camp Gordon was unique in Georgia for its ethnic diversity, including Polish, Greek, Italian, and other immigrants who spoke little English. The Eighty-second played an important role in the epic Meuse-Argonne Offensive that brought the war to an end.

Base Hospital 43 Emory Unit at Camp Gordon, with sponsorship from Emory University, supported a staff of army volunteer doctors, pharmacists, and nurses, including about seventy-one women. After military training, these medics left for France in 1918. Stationed at Blois, they treated about 9,000 patients, with no cross-infections during their tour of duty.

Camp Gordon was significant after the war in many ways. Alvin York, one of the most decorated soldiers of World War I, trained there and was distinguished in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The film Sergeant York (1941), for which actor Gary Cooper won an Academy Award, depicts York’s time in Georgia as a turning point. The noted Georgia historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips also served as a YMCA volunteer at the segregated Camp Gordon, where he confirmed certain racial assumptions on plantation paternalism in his 1918 history American Negro Slavery.

Precedents established at Camp Gordon, which demobilized in 1919, continued during World War II (1941-45). The Eighty-second Division was reestablished at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, as the army’s first Airborne Division, and it continues to use a version of the original AA “All American” red-and-white patch. The Emory unit reconstituted as a civilian medical regiment and served in North Africa during World War II. The Camp Gordon suburban site was first connected with a growing metropolitan Atlanta by an extension of Peachtree Road and trolley service in 1917, and Naval Air Station Atlanta occupied the site during World War II.

Since 1959 DeKalb Peachtree Airport has operated the historic location in Chamblee. Today a historical marker for Camp Gordon, which is sometimes confused with Fort Eisenhower (formerly known as Fort Gordon) in Augusta, stands on the site.

Camp Hancock

Named after Union general Winfield Scott Hancock, a hero at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, during the Civil War, this camp near Augusta consolidated Pennsylvania National Guard units into the Twenty-eighth Infantry Division. The division’s specialties were machine gun and ordnance training, though supplies and equipment were severely lacking. The Twenty-eighth mobilized in 1918 to the Western Front, where it trained with British troops. Like the Eighty-second at Camp Gordon, the Twenty-eighth participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. There it earned the enduring nickname “Iron Division,” after General John Pershing praised the troops as “men of iron.”

After the war ended, the Twenty-eighth developed its distinctive red Keystone patch, returning to its Pennsylvania origins. The division was later distinguished in World War II under General Omar Bradley and afterward resumed its status as a Pennsylvania National Guard Unit. It has continued to serve in combat situations, from the Korean War (1950-53) to the 2003 Iraq War.

Nothing survives of old Camp Hancock in Richmond County, and no historical marker exists.

Camp Wheeler

This cantonment near Macon, also a National Guard mobilization and training camp, was named after Joseph Wheeler, a Georgian who held the rare distinction of serving as both a Confederate general during the Civil War and a U.S. general in the Spanish-American War (1898). Located in Bibb County, Camp Wheeler occupied a 21,000-acre site.

More than 2,400 officers and 87,000 enlistees passed through the cantonment, where the Thirty-first “Dixie” Infantry Division formed and departed for France in 1918. The army, however, dispersed the Thirty-first Infantry troops into other units, and the division members did not see combat together. Today a historical marker marks the site of Camp Wheeler, part of which is occupied by the Macon Downtown Airport, also known as the Herbert Smart Airport.

Fort Oglethorpe Composite Camps

Fort Oglethorpe in Catoosa County, near the Georgia-Tennessee state line, opened in 1904 as a permanent post for the U.S. Sixth Cavalry, which was organized during the Civil War. Named for James Oglethorpe, the founder of colonial Georgia, the fort encompassed three satellite camps during World War I, all located near the Civil War battlefield at Chickamauga.

Camp Greenleaf, a satellite campus with about 10,000 medical, dental, and veterinary officers and 70,000 enlisted medics, nurses, technicians, and assistants, was comprehensive in its training. Named after Charles R. Greenleaf, the chief army surgeon during the Spanish-American War, this training camp peaked with sixty-three base hospitals, thirty-seven evacuation hospitals, five field hospitals, thirteen hospital trains, five ambulance units, twenty-one evacuation ambulance units, and nine convalescent camp companies.

Camp Forrest served as a training base for the Corps of Engineers, infantry, and machine gunners. Named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate hero of the Battle of Chickamauga (and leader of the first Ku Klux Klan, in Tennessee), it is often confused with the World War II training camp in Tullahoma, Tennessee.

The third satellite campus, Camp Warden McLean, was a training school for white officers. Named after an officer trainee who was accidentally killed at Fort Oglethorpe, it became one of the relatively few demobilization centers in Georgia at the end of the war.

After the war, Alvin York received his discharge papers at Fort Oglethorpe before returning home to Tennessee. Today the site of the old Fort Oglethorpe composite military camps is overshadowed by the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, which commemorates the Battle of Chickamauga (1863). The National Park Service took over the site’s management in 1933.

Later Camps

As the Allies mobilized for victory in 1918, the U.S. War Department activated three new sites. Camp Jesup, adjacent to Fort McPherson, was originally a quartermaster depot. Named in memory of General Thomas Sidney Jesup, “father of the Quartermaster Corps” in the nineteenth century, it became a regional repair shop for motor vehicles. German prisoners of war at Fort McPherson constructed nearly 100 buildings at Camp Jesup.

Souther Field near Americus responded to updated Allied needs for modern aerial warfare to complement ground forces. With 16 hangars, 150 aircraft, and 2,000 pilots, it was a U.S. Air Service training camp named in memory of pioneer aviator Major Henry Souther. Souther Field later participated in World War II military aviation, and in 2009 officials rededicated it as the Jimmy Carter Regional Airport.

Camp Benning near Columbus saw its first troops arrive in October 1918, just before the armistice. Located on old plantation grounds and named in memory Henry L. Benning, a Confederate hero and justice of Supreme Court of Georgia, the camp was slated to be the home of the U.S. Infantry School of Arms. Although it opened too late to participate in World War I, Camp Benning became one of Georgia’s greatest army legacies. Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower, later the Supreme Allied Commander during World War II and president of the United States, served at the camp in 1918-19, immediately after the armistice. The U.S. Congress subsequently funded what became the Infantry School there and in 1922 renamed the post Fort Benning, which was again renamed in 2023 as Fort Moore. The site developed into one of the most important military installations in the nation. One of the first soldier recreation facilities there, a memorial to fallen comrades in the Great War, still stands as Doughboy Stadium.