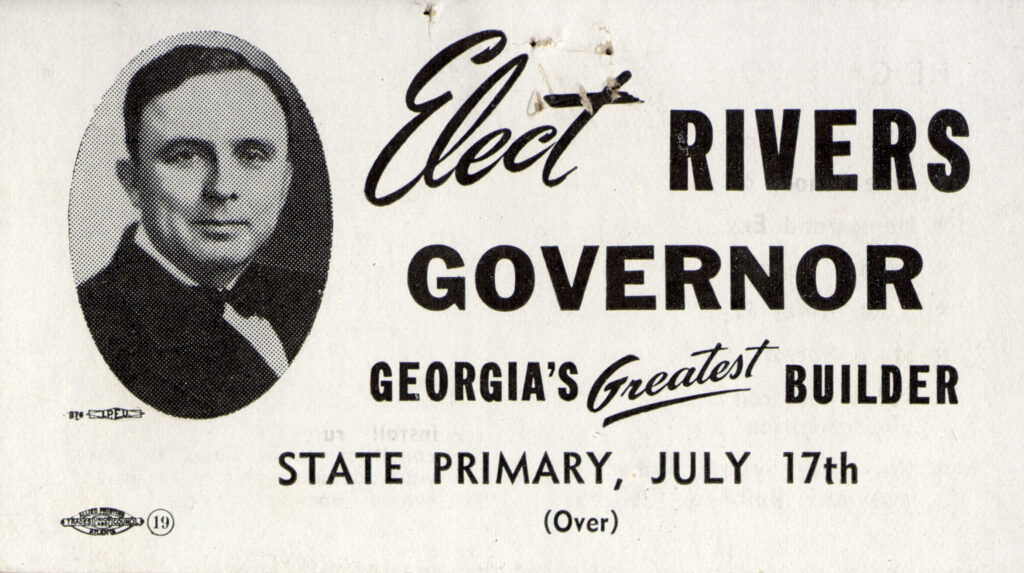

E. D. (“Ed”) Rivers served consecutive two-year terms as Georgia’s governor (elected in 1936 and reelected in 1938). In his first term, Rivers brought a “Little New Deal” to Georgia and presided over a significant expansion of state services. By the end of his second term, Rivers and his administration were awash in charges of corruption. Rivers gained the governorship initially as the anti-Talmadge, pro–New Deal candidate. Yet he used many of the same heavy-handed tactics that his predecessor had made infamous, including the use of the National Guard to resolve political disputes with state agencies. Even when Rivers attempted to return to the governor’s office in 1946, his candidacy served mainly to tilt the race toward Eugene Talmadge.

Courtesy of Georgia Capitol Museum, University of Georgia Libraries

Early Life

Eurith Dickinson Rivers was born on December 1, 1895, in Center Point, Arkansas, to Millie Annie Wilkerson and James Matthew Rivers. He attended Young Harris College, where he met Mattie Lucille Lashley. The two married in 1914 and had two children, Eurith Dickinson Jr. and Geraldine. Rivers earned a law degree from LaSalle Extension University in Illinois in 1923.

The Rivers family settled in Cairo, in Grady County. Soon, Rivers became a justice of the peace, city attorney for Cairo, and attorney for Grady County. He then moved to Milltown (later Lakeland) and became editor of the Lanier County News.

Georgia Politics in the 1920s and 1930s

Rivers quickly established himself as a solid member of the Lanier County elite. He was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1924 and to the state senate in 1926. Like many of Georgia’s rural county leaders, Rivers was active in both the state legislature and the Ku Klux Klan. Despite his surface similarities to the typical Georgia county leader in the period, his biographer describes Rivers as “polished and urbane.” Rivers seemed genuinely concerned for the plight of Georgia’s poor farmers and eventually sought to use the power of government to help them. Politicians like Eugene Talmadge, in contrast, generally opposed state and federal aid programs but were able to connect emotionally with the “wool hat boys.”

Rivers served as speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives from 1933 to 1935 and nominally supported Governor Talmadge. Rivers did not share the governor’s ingrained conservatism, however. Talmadge loudly opposed and obstructed Georgia’s participation in a number of New Deal programs, instead promoting self-reliance and private charity as the answer to Georgia’s Depression-era economic ills. With the popular Talmadge barred from seeking a third consecutive term in 1936, Rivers grasped his opportunity. He openly endorsed the very New Deal programs that Talmadge had opposed and promised more vigorous state government action to promote education, public health, and economic development. The same year, Talmadge challenged Richard B. Russell Jr., also viewed as a supporter of most New Deal programs, for a seat in the U.S. Senate, while a Talmadge supporter, Charles Redwine, bore the conservative standard in the race for governor. Rivers and Russell each won about 60 percent of the popular vote and the majorities in the all-important county unit vote. The New Deal, it seemed, had outpolled Talmadgism.

The Rivers Administration

Rivers pursued an ambitious agenda in his first term. He convinced the legislature to enact legislation making it possible for Georgia to receive federal funds for public housing and rural electrification, measures that Talmadge had blocked. By the end of Rivers’s second term, Georgia had received more than $17 million in federal funds for rural electrification projects alone.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Rivers initiated an active program of state-level government action as well. He convinced the legislature to create independent authorities with the power to sell bonds and incur debt. This was a cumbersome but effective way to allow the state to avoid the constitutional prohibition on state indebtedness, while still borrowing money to fund important public projects. Rivers began new initiatives in public health and prison reform. Probably the most expensive state reforms came in the area of education. In the four years before Rivers became governor, state spending on public education amounted to about $29 million. During his four years in office, the Rivers administration appropriated almost $49 million, including measures to raise teachers’ salaries and provide free textbooks. Rivers’s reforms did not eliminate racial disparities, but these measures benefited Black schools as well as white.

Georgia’s New Deal in Crisis

Rivers received a vote of confidence in the 1938 gubernatorial race, but soon after the election, his administration became embroiled in controversy. The state legislature had enacted ambitious programs but failed to provide adequate funding. Rivers sought new taxes to pay for his programs, but the legislature balked. The governor had little choice but to slash state spending. By the fall of 1939, the state was unable to meet the requirements for teachers’ salaries. Frustrated by the legislature’s refusal to enact a sales tax, Rivers tried to redirect a stream of revenue marked for the highway department to pay teacher salaries. When the state highway commissioner refused to approve Rivers’s action, Rivers used the National Guard to remove him, just as Talmadge had done in a similar controversy earlier. The dispute with the highway department began a long, bitter legal battle in both state and federal courts, during which Georgia’s governor was arrested for refusing to comply with a federal court order. (The arrest was overturned on appeal.) Rivers eventually won the legal battle to divert highway funds over the objections of the commissioner, but the entire affair was a public-relations disaster.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

In 1940 a federal grand jury indicted four members of the Rivers administration on corruption charges. Two were convicted. In 1942 a state grand jury indicted Rivers and nineteen others on various corruption charges. Rivers was accused of selling pardons, though he granted significantly fewer pardons than his predecessor, Talmadge, in comparable four-year periods. Rivers was tried on one count of embezzlement, but the jury deadlocked. Thereafter, Rivers was constitutionally prohibited from seeking a third consecutive term, although it seems unlikely that he could have prevailed in any case.

Legacy

Rivers attempted a comeback in 1946, seeking the governorship in that year’s Democratic primary. Rivers finished a distant third behind his old nemesis, Eugene Talmadge, and Marietta lawyer and businessman James V. Carmichael. Rivers’s presence in the race, splitting the anti-Talmadge vote, very well may have been the deciding factor in allowing Talmadge to win the county unit race (though Carmichael won the popular vote), which led to the infamous constitutional crisis known as the “three governors controversy.”

Rivers’s ambitious reform agenda in the late 1930s attempted to motivate poor white voters in Georgia by offering a program geared toward improving their material well-being. Unlike Talmadge, Rivers was not openly hostile to African Americans, although his private associations clearly indicated that he shared the prevailing racial mores of the day. “In the end,” as historian Numan V. Bartley observes, “Rivers sponsored just enough reform to antagonize county elites without accomplishing enough to persuade [poorer whites] to abandon Talmadge.”

Rivers was never again elected to public office, although he continued to be active in state politics. A successful businessman, he owned several radio stations at the time of his death in Atlanta on June 11, 1967.