Founded amid the social reform movements of the nineteenth century and expanded to one of the nation’s largest mental health institutions in the twentieth century, Central State Hospital at Milledgeville has been at the center of debates over the role of government in public health.

The hospital’s turbulent history, spanning three centuries, has included major changes in how mental illness and people with mental illness are viewed by society and treated by medicine.

Early Planning

Movements to reform prisons, create public schools, and establish state-run hospitals for the mentally ill swept across the nation during the first decades of the nineteenth century. In 1837 Georgia politicians responded by passing a bill calling for the creation of a “State Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum.” Located in Milledgeville, then the state capital, construction of the facility was completed in October 1842, and the hospital admitted its first patient later that year. Initially, politicians expected the asylum would become self-sustaining with healthier patients paying for their upkeep. They also hoped recovered patients could quickly return to society.

Care of patients was based on the “institution as family” model, which asserted that hospitals were best organized when they resembled extended families. This model was applied at Milledgeville under the leadership of Dr. Thomas A. Green, who served at the hospital from 1845 to 1879. Green ate with staff and patients daily and abolished such physical restraints as chains and ropes. Despite these improvements, treatment for patients often varied according to social class, with wealthier patients receiving more attention and treatment than impoverished charges. One wealthy patient stayed in Green’s personal residence (instead of an asylum ward) and married into the superintendent’s family.

The hospital became increasingly custodial as the population evolved from the acutely disturbed to the chronically ill and organically disabled, many of whom were veterans of the Civil War (1861-65) with little chance of successfully returning to their families. Freed African Americans also entered the institution for the first time in 1866, which previously had serviced white patients only.

In 1872 the Georgia Lunatic Asylum possessed a ratio of 112 patients per physician, a number that would not improve for almost a century. The asylum underwent a dramatic increase in patient population when local communities began sending unwanted or problematic residents to the asylum, regardless of their diagnoses. This included many freedpeople who were deemed unfit for independent living according to the principles of scientific racism. The asylum’s population further accelerated in 1877 when it ended any expectation that patients or their families pay for their upkeep at the institution.

Rapid Expansion

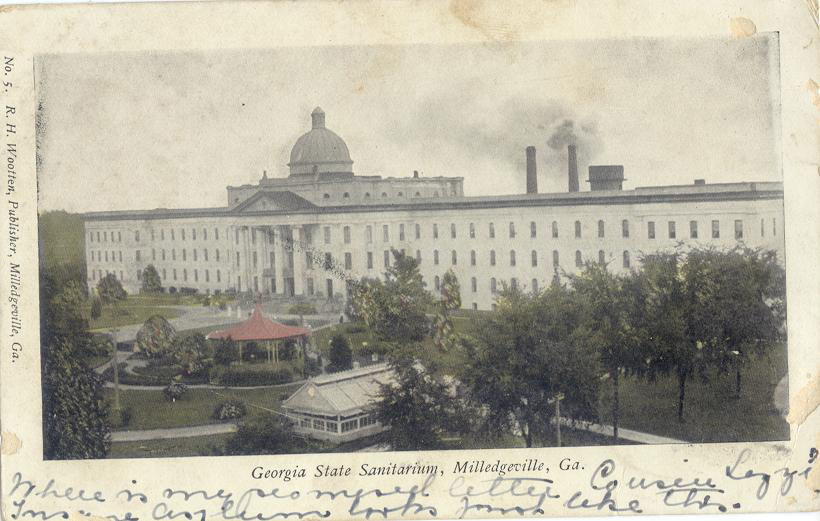

The asylum adjusted to this increase by developing more specific methods of diagnosis and implementing differentiated ward placements under Superintendent Dr. Theophilus O. Powell, a noted scholar of psychiatry, who served from 1879 to 1907. Powell segregated Black patients into their own building, one of several additional brick buildings and numerous auxiliary facilities constructed to handle the increase of patients. New construction often failed to keep up with overcrowded wards, however—a problem exacerbated when the building for African Americans burned in 1897. Powell resorted to housing Black patients in underground tunnels until the building could be rebuilt. That same year, the Georgia Lunatic Asylum changed its name to the Georgia State Sanitarium.

Crowded conditions led to the spread of infectious diseases like tuberculosis, which prompted a legislative inquiry into management at the sanitarium in 1909. Nevertheless, counties continued to send unwanted residents to the sanitarium, and the increase in numbers meant a concurrent decrease in the quality of care.

Feeding the sanitarium’s population (which numbered 3,206 patients at the start of 1910) became prohibitively expensive, so officials sought to become self-sufficient. Part of the extensive hospital grounds had been reserved for the planting of crops, and administrators had patients undertake the strenuous work of farming these acres. The work entailed little treatment on the part of the staff but often proved beneficial to those patients who would return to farm life when discharged. The overwhelming number of patients also led to a pattern of conscious neglect, whereby hospital staff met the basic daily needs of their charges but were unable to provide appropriate treatment for their illnesses.

In 1929 the state legislature changed the name of the sanitarium to Milledgeville State Hospital, reflecting a focus on rehabilitating its 5,000-plus patients. But significant interventions like insulin shock and electro-convulsive therapy became common to manage the exploding patient load. Federal funds assisted in the construction of needed additional buildings by 1940, but the dislocations of the Great Depression swelled the hospital’s patient count past 9,000.

Political Challenges

The advent of psychotropic drugs reduced the length of stay and made home return more feasible for acute patients, but the ultimate goal of reducing the patient population clashed with the institution’s political self-interest. Politicians frequently interfered with the hospital, with Governor Eugene Talmadge firing superintendents at whim, while Speaker of the House Roy V. Harris and Senator Culver Kidd of Milledgeville were accused of coercing hospital administrators into hiring political patrons to fill jobs that a reduction in patient population would endanger. When Superintendent Dr. Y. H. Yarbrough resigned in 1948, he jested that he was “the only superintendent who hasn’t been kicked out, or carried out feet first in a casket.”

By the late 1950s, the hospital had an average of over 11,800 patients, making it the nation’s largest mental hospital next to New York’s Pilgrim State Hospital. A series of damning articles in 1959 by Atlanta Constitution reporter Jack Nelson (who would win a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage) revealed several abuses at Milledgeville State Hospital: experimental drugs being given to patients without their or their family’s consent, a nurse performing major surgery without supervision, and staff and doctors being drunk while on duty. In response, Governor Ernest Vandiver Jr. called on a commission to investigate and recommend legislative action.

Despite concerns that another investigation would not materially improve the hospital’s staffing crisis and treatment of its patients, state officials nevertheless took measurable action. A regional system of six additional mental hospitals was established, with Milledgeville State Hospital being renamed Central State Hospital in 1967 to reflect its central location. With a shift from a medical to a mixed-therapy model, patients were increasingly released from Central State, which in 1968 dropped below 10,000 patients for the first time in two decades. That same year, the hospital closed its farm, and the land was parceled out among other state agencies, including the Georgia Department of Corrections.

Dispersal and Closure

In the last three decades of the twentieth century, advocates for the mentally ill, including Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter, pushed for more flexibility in getting patients back into society. A U.S. Supreme Court case involving Georgia’s mental hospitals, Olmstead v. L.C. in 1999, accelerated this trend by requiring hospitals to allow patients to leave if community treatment was possible and the patients desired it. Advocates also began the process of identifying and marking thousands of unmarked graves at Central State Hospital.

The first decades of the twenty-first century presented new challenges for Georgians with mental illness. Years of budget cuts at the seven state hospitals led to severe staff shortages and several preventable patient deaths. An investigation by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2007 called “A Hidden Shame” prompted another public outcry and a threatened lawsuit against the state by the U.S. Department of Justice. As part of the settlement, Georgia’s hospitals were largely shut in favor of community treatment. But with state revenue depleted during the Great Recession, community treatment programs ran into many of the same obstacles that plagued the old hospitals, including inadequate funding and poor standards of care. Even so, by the start of 2010, only thirty patients remained at Central State, and by year’s end only a unit to temporarily house and treat mentally ill criminal defendants remained.

With patients all but gone, the dozens of deteriorating buildings are all that remains of Central State Hospital. The site is now a patchwork of state and private ownership, with much of the area managed by a local redevelopment authority. Preservationists have campaigned to save the many structures still left, and the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation has twice selected Central State Hospital for its annual “Places in Peril” list.