From the late eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century, there was no more important single factor in Georgia’s agricultural economy than cotton. In 2014 the state ranked second in cotton production in the United States, behind Texas, planting 1.4 million acres.

Introduction of Cotton

Photograph by Michael Bass-Deschenes

There was little indication at the time of the American Revolution (1775-83) that cotton would become an integral part of the state’s history. Georgians imported Sea Island cotton from the West Indies to the state’s coastal areas around 1785 and, after some difficulty, successfully produced small amounts of cotton. In 1801, for instance, the state produced 21,000 bales on 65,000 acres. Sea Island cotton produced a long, strong fiber, which was easily separated from the seed (a problem that plagued the shorter-staple upland variety), but Sea Island cotton could be grown only along the coast, where the growing season was quite long. Two developments in the late eighteenth century would move Georgia farmers away from Sea Island cotton—the beginning of Indian removal (and the concurrent westward movement of English and Spanish settlers from the developed ports of Savannah and Augusta) and the invention and perfection of the cotton gin.

After the forced removal of the Creeks in the 1810s and the Cherokees in the late 1830s, more white settlers moved west from the coast, developing some of the South’s most productive farmland. The rich soil could produce a variety of products, though cotton was still too expensive and labor-intensive to grow on a large scale because of the difficulty of picking the seeds from the fiber. This western settlement, however, coincided with the perfection of the cotton gin, a machine that easily separated the seeds and fiber. The gin, invented by Eli Whitney in Chatham County in 1793, allowed farmers who had enough land and labor to grow short-staple cotton profitably. Hungry for land on which to plant this suddenly worthwhile crop, Georgians grabbed land all over the state. The counties connecting Augusta and Columbus were ideal for cotton, though almost any flat, rich soil became a cotton field.

Photograph by Kimberly Varderman

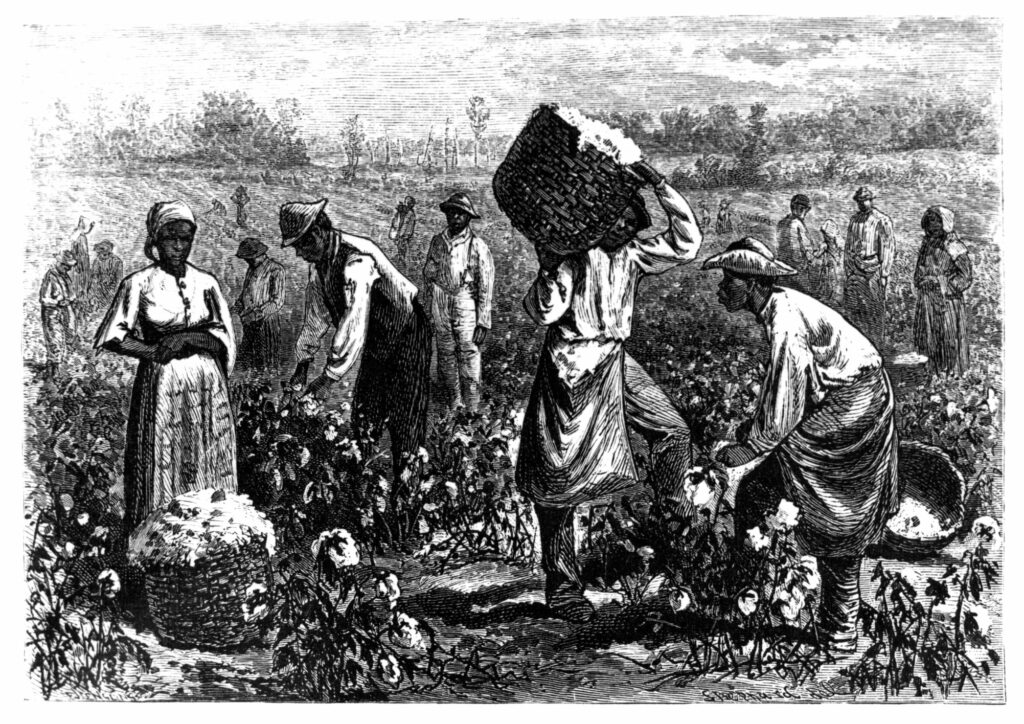

With cotton came slavery. Since the success of a labor-intensive crop like cotton was directly tied to the ability of a landowner to procure workers, white Georgians became heavily dependant on the stolen labor, knowledge, and skills of enslaved African Americans. The promise of a bumper cotton crop not only changed the state’s agricultural history but also literally caused the enslavement of hundreds of thousands of men and women. Enslaved Georgians planted, chopped, and picked cotton; they cleared and dug drainage ditches to create more cotton land. The international slave trade geared up to meet this new labor demand, and as a result, slavery and cotton tightened their grip on the state and left their unmistakable, tragic mark internationally. From 1791 to 1801 Georgia’s cotton production increased by a factor of twenty.

Antebellum Cotton

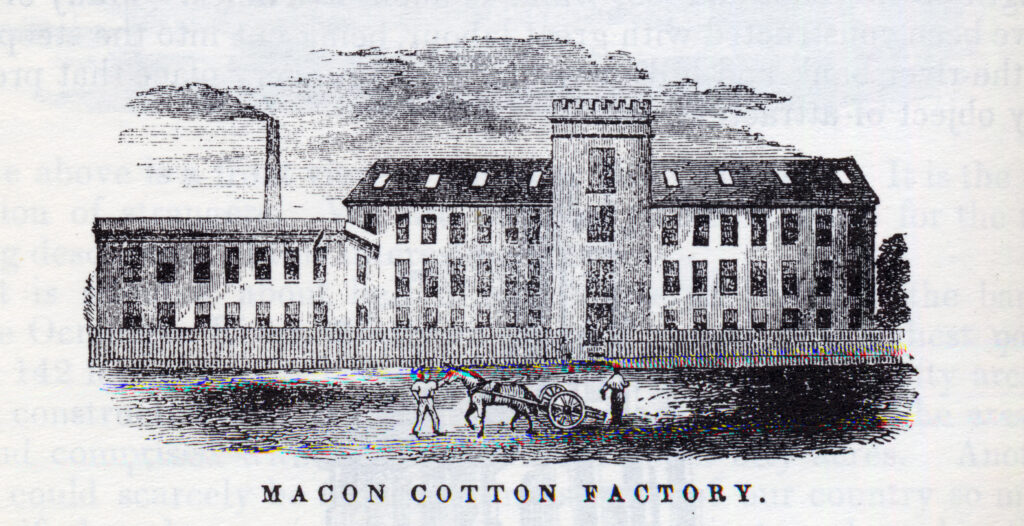

The market for Georgia’s cotton grew throughout the nineteenth century. The War of 1812 (1812-15) cut the United States off from the British Empire’s cotton supply, and Americans became dependent on their own production. New England industrialists recognized the potential for a domestic textile industry and began financing textile mills. Advances in loom technology allowed American mills to compete with their British counterparts and boosted demand for southern cotton. In addition to the increased demand, Georgians developed vast transportation networks that efficiently carried the cotton from the farms to rivers and eventually to the major port cities of the state’s coast.

During the years leading up to the Civil War (1861-65), enslaved labor and land became more expensive and harder to find. The scarcity of land pushed farmers to try their luck on less suitable soil, but with cotton prices relatively high, many of these gambles initially paid off. Cotton growing could be immensely profitable, and for thousands of Georgians it was. During this period entire towns, complete with banks, schools, stores, and other businesses, sprang up to serve the needs of a successful cotton-producing area. Everyone with sufficient capital tried cotton farming; many doctors, lawyers, bankers, and insurance men had their professional lives in town and a cotton field a few miles into the country.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The widespread success of cotton divided Georgia’s classes top to bottom, from planter to bondsman. In addition to the unmistakable mark the plant left on Black-white relations in the state, it affected gender relationships. Women’s roles on Georgia cotton farms varied according to geography, farm size, and other factors, but generally women helped chop and pick cotton, besides performing a host of difficult, monotonous household duties.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

Cotton played an important role in Georgia’s entry into the war, its wartime experience, and its postwar efforts to rebuild. Without the South’s obsession with cotton, it is hard to imagine that the Civil War would have occurred at all. Once the war began, the Confederacy attempted to use cotton as a weapon by starving the North of the crop and by courting European support with it. Neither strategy worked, however, because the superior Union navy blockaded Confederate ports, choking both intraregional and international trade. Domestic sentiment in Britain against slavery kept that nation’s navy out of the conflict, despite the severe disruption of cotton production in England. After the war the most important issue to white slaveholders was that many of their best cotton fields lay in disrepair and their cotton field labor—enslaved people—had been emancipated. Georgia’s 1865 total agricultural wealth was a mere 20 percent of what it had been when war broke out.

During Reconstruction cotton planters worked hard to recover and rebuild their cotton operations. The primary obstacle that planters faced in rebuilding their plantations was neither the condition of their fields nor the intrusion of federal officials but rather the new condition of free labor for the state’s Black population. Though most freedmen imagined that they would acquire land and become self-sufficient cotton farmers, soon after the war it became apparent that the rural white elite would not give up their control of cotton production so easily. What developed were systems of tenancy, including sharecropping, which took a variety of forms. With a predominantly Black workforce back in the fields, and with cotton mills once more multiplying in the state (especially in west central Georgia), cotton again became the king of Georgia’s economy.

Cotton in the Twentieth Century

As the twentieth century began, “New South” boosters and Progressives, from their offices in Georgia’s cities, implored the state’s farmers to diversify their crops. The state’s dependence on cotton was too severe and risky, they argued, and it inhibited the state’s modernization. These pleas fell on deaf ears; many Georgians continued to plant cotton up to the front door and bought items in local stores that their parents and grandparents would have produced on the farm.

Courtesy of Thomaston-Upson Archives

As a result, Georgia’s cotton economy peaked on the eve of World War I (1917-18). Georgia produced a record 2.8 million bales on 4.9 million acres in 1911. The boll weevil arrived four years later. The weevil, cotton’s greatest enemy, not only cut production levels in half in many areas but also increased the mass migration of white and Black tenant farmers from rural Georgia in the Great Migration that began during World War I. The insect reduced the state’s cotton yields an average of 29 percent from 1918 to 1924.

Changes brought by the weevil, the New Deal, and World War II (1941-45) continued to threaten cotton and all of those who relied on it. The New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Act reduced cotton acreage in the state, with the hope of driving up the price of the staple crop, but the acreage reductions also decreased the need for labor. Tractors, beginning in the 1930s, and mechanical cotton pickers decades later, further disrupted cotton production and the lives of those who worked in the fields. Cotton prices worldwide began to fall during the middle of the century as viable synthetic alternatives decreased demand for the fiber.

Photograph from the Agricultural Research Service

According to the Georgia Crop Reporting Service, by 1957 the state produced only 396,000 bales on 570,000 acres, and the numbers continued to drop. In 1987 a means of boll weevil eradication was finally developed, and in 1990 the pest was eradicated in the state. Many counties, especially in south Georgia, began to turn back to the crop. From 1983 to 1994, for example, Lee County’s cotton production jumped from 64 to 17,800 acres.

Cotton in the Twenty-first Century

Thanks to mechanization, boll weevil control, federally funded programs, and a move to corporate farming, Georgians successfully farm cotton today not only in the rich fields of south Georgia but also, to a limited degree, in the valleys and flat spots of north Georgia. Technology has changed how farmers pick the cotton; global positioning systems guide planting; computers run gins. Cotton farming is no longer the realm of the small farmer, however. Most of the cotton in the state is produced by agribusinesses that manage large tracts of cotton land. Cotton production in the state is currently almost back to pre–boll weevil levels, though this modern cotton farming bears little resemblance to the farming of the 1930s and earlier.

Photograph from the Agricultural Research Service