Over the course of forty-eight years, Savannah played an integral role in the Atlantic slave trade. Although Savannah’s participation in the slave trade was initially miniscule, the port of Savannah has historical transnational importance as a receiver of enslaved West Africans during the late eighteenth century. Despite a ban on African slavery in early Georgia, enslaved people and slavery were an integral part of the colony’s development. Following the settlement of Savannah in 1733, enslaved people from South Carolina cleared land, tended cattle, and labored on farms. By the late 1740s enslaved people from South Carolina were openly sold in Savannah. The legalization of slavery in Georgia in 1750, by the Trustees who governed the Georgia colony, extended an official imprimatur to a reality that already existed.

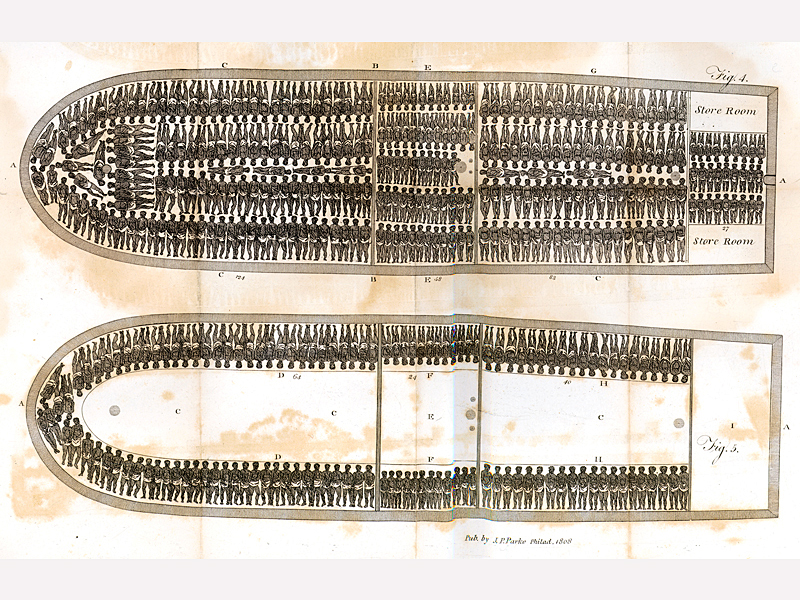

From The History of Rise, Progress & Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-trade by the British Parliament, by Thomas Clarkson

The repeal of the ban on African slavery marked the beginning of Savannah’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. Savannah’s propitious location near the Atlantic Ocean and the coastal region’s navigable rivers and waterways allowed commercial vessels to enter and leave the area easily. Merchants, planters, and politicians actively directed the city’s involvement in the trade until 1798, when the Georgia legislature banned the slave trade from Africa.

The demand for African enslaved labor increased with the establishment of rice and Sea Island cotton plantations in the Georgia Lowcountry. As rice became a profitable export crop in coastal Georgia, merchants in Savannah imported Africans from the rice and grain coast of West Africa, which extended from the Senegambian region to Sierra Leone. Before enslaved West Africans were imported directly, Savannah’s merchants and planters secured African captives via the intercolonial trade with South Carolina and the Atlantic trade with the Caribbean. In 1747 the merchant firm of James Habersham and Francis Harris built one of several commercial vessels, the schooner Endeavour, to engage in the intercolonial trade. The Endeavour exported goods to South Carolina for reexport to Britain and imported enslaved people from South Carolina for sale in Savannah. The success of the Endeavour led to the construction of additional commercial vessels that engaged in the intercolonial trade and the Atlantic trade with the Caribbean and Africa. During the early period of Savannah’s involvement in the trade, from 1755 to 1767, 63 percent of enslaved people imported into Savannah originated from the Caribbean, and 24 percent came directly from Africa’s rice and grain coast. During the intermediate period from 1768 to 1771, 86 percent of enslaved people imported into Savannah originated from Africa.

During the American Revolution (1775-83), the Continental Congress’s nonimportation agreement of 1775, which banned all slave trade, disrupted the Atlantic trade to Savannah. From 1778 to 1783 the hostilities between the American colonists and the British extended to Africa, as a result of a French alliance with the American colonies in 1778. This alliance exacerbated hostilities between Great Britain and France, who also were waging war in Africa to maintain zones of influence over important slave forts along the West African coast, such as St. James in the Gambia River, St. Louis in Senegal, and Goree Island off the coast of Senegal.

Throughout their involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, merchants and planters in Savannah imported enslaved people from St. James and Goree Island, two of Britain’s significant supply zones for captive workers. Other supply zones for the Savannah market included the British colony Sierra Leone, located along the Windward Coast of West Africa. After the Revolutionary War the slave trade to Savannah resumed. Between 1784 and 1798, enslaved West Africans accounted for 78 percent of enslaved people imported to Savannah.

The Liverpool Trade and Lazaretto

Merchants and ship owners in Liverpool, England, maintained intercontinental communication with merchants and plantation owners in Savannah. The Liverpool trade replaced the defunct Royal African Company, which operated from the port of London from 1672 to 1752. The earliest direct shipment of West Africans to Savannah occurred via the Liverpool trade in 1766 when the Liverpool sloop Maryborow arrived in Savannah from Senegal with seventy-eight enslaved people. The Liverpool merchants John and Matthew Strong, the owners of the Maryborow, instructed the ship’s captain, David Morton, to consign the men and women to the mercantile firm of Broughton and Smith in Savannah.

The voyage across the Atlantic Ocean from West Africa to Savannah lasted between four and six months. The duration of the voyage combined with the prolonged confinement increased the occurrence of infectious diseases. To prevent the spread of disease in Savannah, city officials in 1767 authorized the construction of a nine-story quarantine facility, a lazaretto (Italian for “pest house”), on the west end of Tybee Island. Before entering the Savannah port, enslaved people brought directly from West Africa remained quarantined at Lazaretto, where a physician who determined if they harbored infectious diseases inspected them. Diseased individuals remained at the facility. Those who died from disease were buried on the west end of Tybee Island.

In the last years of the century Georgia officials enacted laws restricting Savannah’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. In 1798 the state legislature banned the direct importation of Africans. This measure preceded by ten years the national ban on the slave trade from Africa, which led to an illegal slave trade that persisted for many decades. The deep waterways of coastal Georgia offered good harbor for this trade, which continued as late as 1858, when the slave ship Wanderer landed near St. Simons Island with more than 400 African captives.