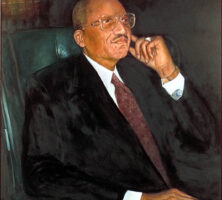

Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

Black Leaders of the Civil Rights Movement

The Black leaders of the civil rights movement came from a variety of backgrounds, but they were all united under a common goal—racial justice. Their work began well before the 1950s and continued far beyond the death in 1968 of Martin Luther King Jr.

Introduction

Georgia has been home to a number of major figures who participated throughout the twentieth century in the struggle for civil rights. Many of these nonviolent activists rose to national attention during the 1950s and 1960s through their personal bravery and the public exposure they brought to injustices occurring in the South. However, it was not these activists alone who contributed to the advancement of civil rights—civil rights leaders also included lawyers, educators, ministers, and politicians who founded institutions to facilitate change and to support and educate those protesting in the streets. Their work began well before the 1950s and continued far beyond the death in 1968 of Martin Luther King Jr. The Black leaders of the civil rights movement came from a variety of backgrounds, but they were all united under a common goal—racial justice.

Organizing Suffrage

The first half of the twentieth century saw the emergence of numerous organizations that would serve to advance Black suffrage and civil rights, the issues at the heart of the movement.

In 1918 Atlanta native Walter White, one of the most prominent African American spokesmen in the United States, joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and contributed to the organization’s emergence as a crucial tool in the progression of civil rights. In 1929 White became the chief secretary of the NAACP, and through the organization he investigated race riots and exposed lynchings, thereby bringing wider attention to the civil rights cause.

Born in 1882, John Wesley Dobbs represented the emergence of socially conscious, Black middle-class leaders who viewed suffrage as the key to racial advancement. Dobbs’s goal was to instill ideas of equality and leadership in Atlanta’s African American community, and he experienced several successes during the 1940s. In 1946 Dobbs cofounded the Atlanta Negro Voters League, and at his urging Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield hired eight African American police officers for the city in 1948.

Active in the same period as Dobbs, Clarence A. Bacote was a political activist also striving to increase African Americans’ political participation. Bacote’s goal was to educate Black voters in Atlanta, and he achieved this through his work as chair of the Atlanta All-Citizens Registration Committee. Under Bacote’s guidance in 1946, the number of Black registered voters in Atlanta increased from 6,976 to 21,244 in fewer than five months.

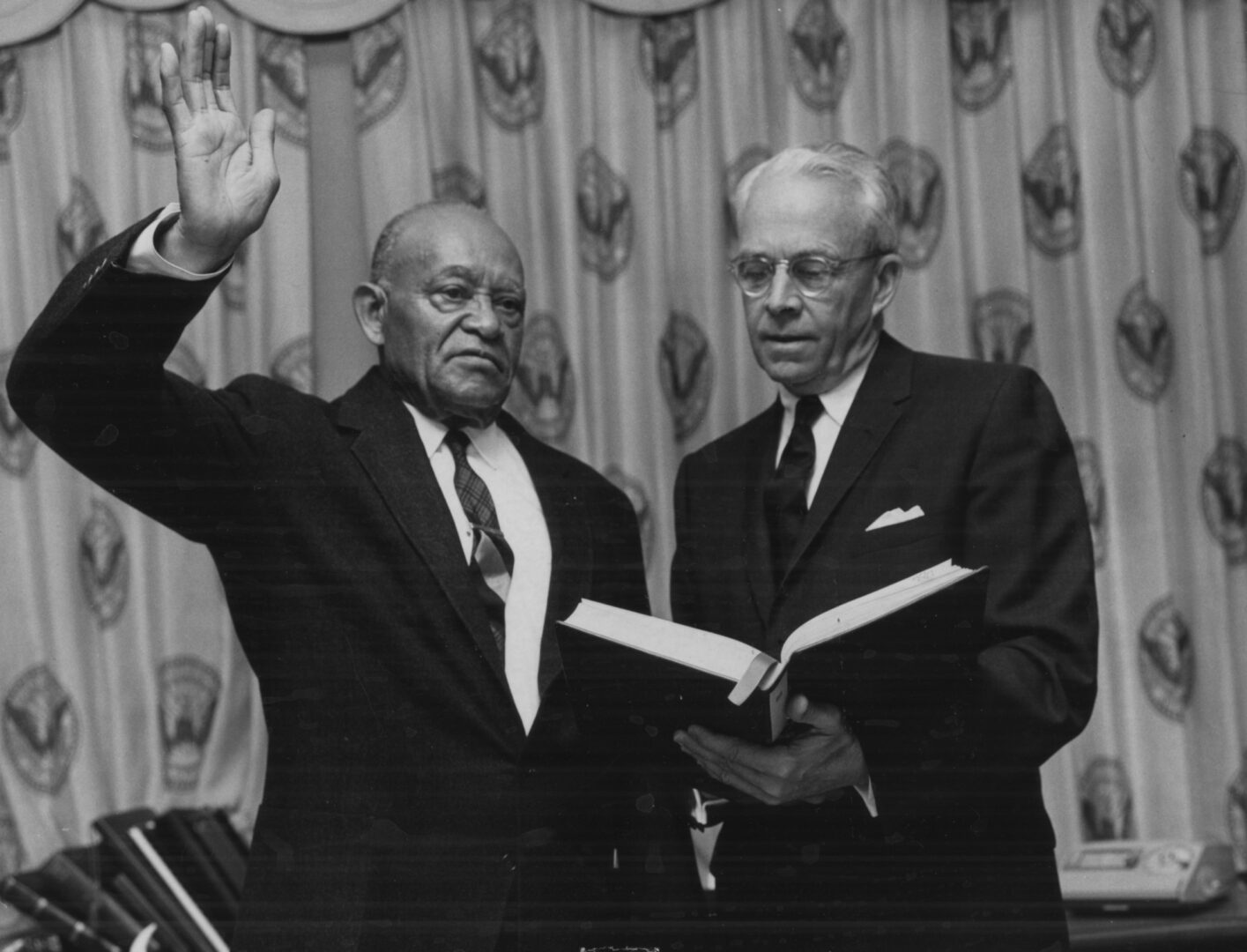

One of the New South’s first Black political power brokers, civil rights attorney A. T. Walden assumed leadership roles in the Atlanta branch of the NAACP and the Atlanta Urban League, both significant institutions for the movement. He also cofounded the Atlanta Negro Voters League in 1949 and served in leadership positions for the All-Citizens Registration Committee.

The Self-Made Man

Civil rights professionals and activists were not always born into the Black middle class. Many fully understood the consequences of poverty and racism that were challenged by the movement, and their backgrounds provided unique perspectives that helped them to facilitate change.

Born into poverty in 1884, Benjamin Mays provides a clear example of the self-made man. Refusing to be defeated by his circumstances, Mays fought for the education necessary to become a minister, scholar, and social activist. He also assumed several leadership roles in various organizations of the civil rights movement. In 1940 Mays became president of Morehouse College in Atlanta. There, he mentored his most famous student, Martin Luther King Jr. Mays’s two main ideas were his belief in the dignity of all human beings and the incompatibility of American democratic ideals with American social practices. It was these social practices, including segregation, that the civil rights movement aimed to change.

Another self-made man, W. W. Law was born in Savannah and began working at the age of ten to help support his family. His civil rights activism began early, while he was in high school, and he credited his later success to his grandmother Lillie Belle Wallace, who instilled in him a love for reading and social justice. Law served as president of the Savannah chapter of the NAACP from 1950 to 1976 and became known (as was civil rights attorney Donald Hollowell) as “Mr. Civil Rights.” After his retirement, Law founded the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, named for his mentor and the pastor of First African Baptist Church in Savannah.

These men, and others like them, served as models and inspiration for members of their own and subsequent generations of civil rights activists.

Legal Standing

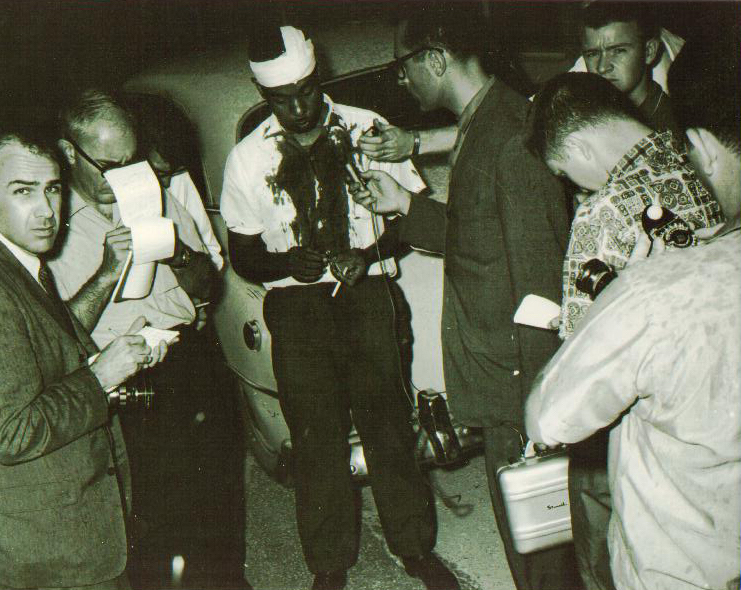

To achieve changes in social practices, African Americans needed members of their own community in positions of legal power. C. B. King, one of the few Black lawyers in Georgia during the 1950s, became an inspiration to generations of lawyers and activists. King repeatedly came into the firing line of white racism while defending civil rights activists, but this did not deter him. Providing further legal backing, Leroy Johnson in 1962 became the first African American to be elected to the Georgia General Assembly since Reconstruction.

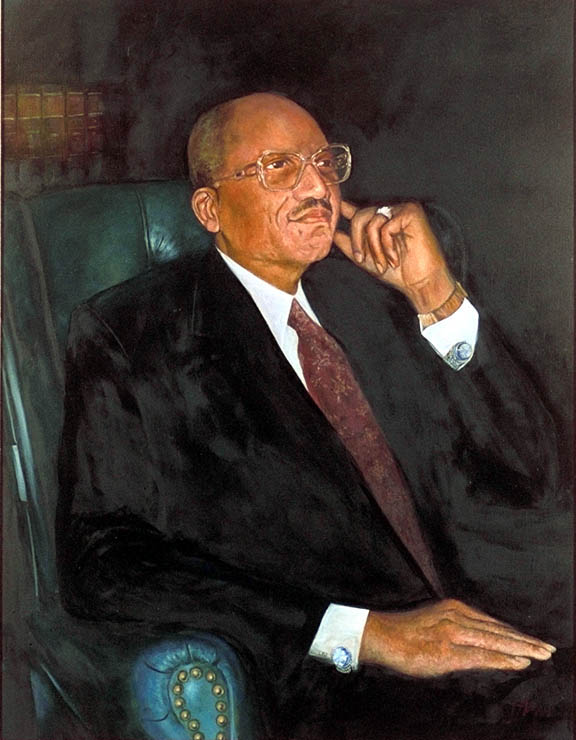

The desegregation of education was essential on the road to equality, and this cause was taken up by Donald Hollowell. As one of only a handful of Black lawyers practicing civil rights law in the 1950s and 1960s, Hollowell became the most prominent attorney for social justice, gaining the nickname “Mr. Civil Rights.” In addition to representing Martin Luther King Jr. in court, Hollowell achieved a momentous victory against the University of Georgia with regard to state-sanctioned segregation in 1956. Horace T. Ward, who later became the first African American to serve as a judge on the federal bench in Georgia, also came into conflict with UGA as he challenged the university’s segregationist policies. His efforts contributed to the admission of two African American students in 1961.

Grace Towns Hamilton was the first African American woman to be elected to the Georgia General Assembly in 1965. Hamilton began her career as a teacher and helped to develop interracial programs on numerous college campuses. In 1943 she was appointed executive director of the Atlanta Urban League and strove for advances in education, voting rights, and health care for African Americans. During her career in the Georgia legislature, Hamilton worked to expand political representation for African Americans in the South, becoming known to her peers as “the most effective woman legislator the state has ever had.”

These individuals contributed to an African American legal support system that had emerged to defend the civil rights movement. This development was crucial, since the legality of customs supporting white supremacy was a major obstacle to bringing about change.

The Kings

Martin Luther King Jr., an Atlanta native, first became involved in the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama, where he headed the Montgomery Improvement Association and, with activist Ralph David Abernathy, organized the Montgomery bus boycotts in 1955. The boycotts led to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1956 that segregation on Montgomery buses was unconstitutional.

In August 1957 King and Abernathy launched the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Atlanta, with King serving as president. Over the next decade, King led the March on Washington in 1963, which promoted the importance of equality and jobs for African Americans, and carried on the work for suffrage begun by Dobbs and Bacote. In 1965 he was present when U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into federal law. King worked tirelessly to reinforce his nonviolent approach in the face of rising Black power but was shot dead in 1968 while supporting a workers’ strike in Memphis, Tennessee.

King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, was an influential activist in her own right. Scott King was present at both the March on Washington in 1963 and the Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama in 1965, and she often used her singing talents to raise funds for these protests. Other women, including Bernice Johnson Reagon, also used the power of music to express their support for the civil rights movement.

Scott King traveled to India with her husband in 1959 to study the philosophy of civil disobedience pioneered by Mahatma Gandhi decades earlier, but her focus remained in the South. She went to Memphis immediately after her husband’s death to oversee the march that he had been planning and soon thereafter established the King Center in Atlanta to honor his life and work. She later worked for the National Organization for Women on the Equal Rights Amendment, and in the 1980s she worked with anti-apartheid groups in South Africa, where she established friendships with both Winnie and Nelson Mandela. In recognition of her contributions, Scott King became the first woman and the first African American after her death to lie in state at the capitol rotunda in Atlanta.

Activism in the Movement

The work on the ground during the 1950s and 1960s is one of the best-known stories of the civil rights movement. The activism of those who took to the streets in Georgia is represented by the careers of two significant figures.

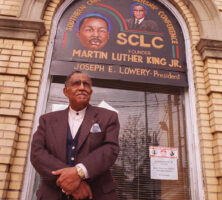

Inspired by the Montgomery bus boycotts, the Methodist minister Joseph Lowery, known as the “dean of the civil rights movement,” led a successful drive against the segregated bus system in Mobile, Alabama. A cofounder of the SCLC, Lowery remained an active participant in the organization for decades. In 1968 he moved to Atlanta, where he worked with the SCLC to increase Black voter registration, and from 1977 to 1997 he served as the organization’s president. In 2009 he delivered the benediction at the inaugural ceremony of Barack Obama, the nation’s first African American president.

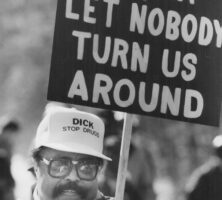

Hosea Williams was a pastor and a vocal political activist. During the early 1960s he served as vice president of the NAACP in Savannah. Working with W. W. Law, the president of the chapter, he coordinated protests that led to Savannah becoming the first Georgia city to desegregate its lunch counters. In 1965 Williams, along with activist John Lewis, organized the historic Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama, which televised to the entire nation the police brutality toward peaceful protesters. Williams later organized the 1987 Brotherhood March in then all-white Forsyth County to honor Martin Luther King Jr.

Civil Rights as Big Business

With the growth of Atlanta and other cities in the South, African Americans began to use business and academia to aid social change in ways other than protests and demonstrations.

In 1960 businessman Jesse Hill and Atlanta Urban League executive director Grace Towns Hamilton produced a survey entitled “A Second Look: The Negro Citizen in Atlanta.” This document questioned the predominant belief in the white community that Atlanta, known as “the City Too Busy to Hate,” was a shining beacon for racial harmony in the South. Hill went on to challenge college segregation in Georgia by recruiting African American students Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter to apply to the University of Georgia. With Hill’s backing, the two were admitted in 1961, thereby integrating UGA.

As president of Atlanta Life Insurance Company from 1973 to 1992, Hill promoted civil rights in Georgia and Alabama by raising money and exposure for the movement. The Reverend William Holmes Borders, pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church in Atlanta and a key advocate of the relationship between economic freedom and civil rights, worked with Hill to gain donations from Atlanta Life. These funds allowed Borders’s church to construct low-income housing for the African American community.

Borders’s project influenced others to work toward economic independence as well. Slater King, vice president of the Albany Movement and an Albany real estate broker, worked throughout the 1960s to promote socioeconomic development through home ownership in Dougherty County.

The Civil Rights Legacy

Rather than causing the civil rights movement to dissolve, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 galvanized a new wave of activists, politicians, and academics to carry forward the civil rights mission for the remainder of the twentieth century and beyond.

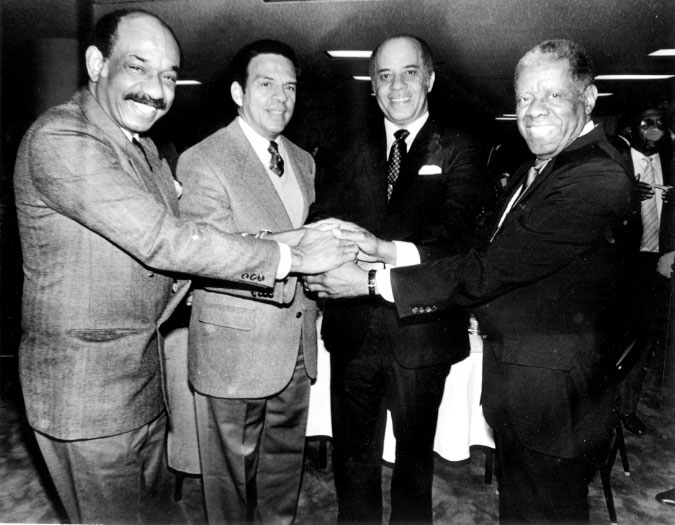

Andrew Young had worked under King in the SCLC, but when King was murdered, Young used the tragedy to strengthen his own voice politically. In 1972 Young became the first African American since Reconstruction to be elected from Georgia to the U.S. Congress. The voter registration campaigns that Young and his wife, Jean Childs Young, helped to organize throughout the South in the 1950s and 1960s also bore fruit, resulting in the election of thousands of African American candidates to higher office over the ensuing decades.

Similarly, John Lewis became a groundbreaking figure in southern politics after retiring from his position as chair of the Atlanta Student Nonviolent Committee (SNCC) in 1966. In 1986 Lewis won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and served as a U.S. congressman for more than thirty years until his death in 2020. Julian Bond also experienced great political success following his involvement with SNCC, being reelected into the Georgia state legislature more times than any other Black Georgian by the time he retired in 1986.

The prominent African American lawyer Vernon Jordan, in addition to being the field director of the NAACP, became executive director in 1970 of the United Negro College Fund, which raised $10 million in his first year. Two years later, Jordan also became executive director of the National Urban League, which works to secure economic self-reliance, parity, and civil rights for African Americans.