The New Georgia Encyclopedia is supported by funding from A More Perfect Union, a special initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

A folklorist and professor of English at Georgia State University in Atlanta, John A. Burrison has helped shape an entire academic field of specialty, that of folk pottery. He holds a couple of face "jugs."

Courtesy of John Burrison. Photograph by Carolyn Richardson

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Mossy Creek potter Lanier Meaders (left) with folklorist John A. Burrison in 1970. The painted vases on the kiln were made by Lanier's mother, Arie Meaders. The Meaders family is one of the best-known traditional potter families in northeast Georgia.

Courtesy of John Burrison. Photograph by Dick Pillsbury

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Singers perform during the Sapelo Island Cultural Day, held each October on the island. The festival celebrates the songs, stories, dances, and food of the Geechee and Gullah culture, which developed on the Sea Islands among enslaved West Africans between 1750 and 1865.

Photograph by Jennifer Cruse Sanders

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

In the same manner as their enslaved ancestors, women on Sapelo Island hull rice with a mortar and pestle, circa 1925. Language and cultural traditions from West Africa were retained in the Geechee culture that developed in the Sea Islands.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

sap093.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Praise houses were built on plantations by enslaved people for worship services. These services often included the ring shout, in which rhythmic hand clapping and counterclockwise dancing were performed to spirituals.

Image from Richard N Horne

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Baindu Jabati (left) and Mary Moran were the only two women to remember a Mende funeral song performed as part of the village tradition in Senehun Ngola, Sierra Leone. The song was passed down through Moran's family in Georgia from her enslaved ancestors, who were related to Jabati's ancestors in Sierra Leone.

Photograph by Sharon Maybarduk

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Georgia Sea Islands are the site of the unique Geechee and Gullah culture, which retains ethnic traditions from West Africa brought to America during the years of the Atlantic slave trade. Although elements of the culture persist, its survival is threatened by development on the islands.

Photograph by WIDTTF

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The ship the Morning Star receiving the Blessing of the Fleet, a centuries-old tradition orginally meant to bring a bountiful harvest, now takes place in Brunswick on Mother's Day as a procession of decorated ships.

Courtesy of Georgia Council for the Arts.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Council for the Arts.

Georgia's immigrants have brought with them a diversity of languages, religious practices, food and craft traditions, music, styles of dress and decoration, and ways of celebrating.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to Special Collections and Archives at Georgia State University.

A band plays during Savannah's annual St. Patrick's Day parade. Irish Americans continue to flock to Savannah for this celebration.

Image from Jefferson Davis

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Several thousand visitors from across the state converge for the final event of the festival. Known as a "Day in the Park," the event showcases African pride and accomplishment and is held in Macon's Central City Park on the last Saturday in April.

Courtesy of Tubman African American Museum.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the Tubman African American Museum.

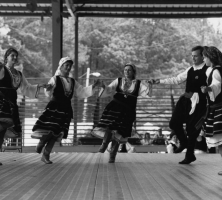

The Greek Festival is an "outreach" celebration, meaning noncommunity members can participate in festival events.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to Special Collections and Archives at Georgia State University.

Pig racing is a popular event at the Georgia Mountain Fair. Also popular: pork for lunch.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

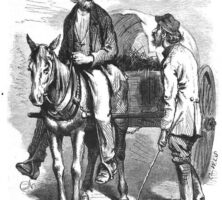

By the 1760s the English, both at home and in colonial America, were applying the term cracker to Scots-Irish settlers of the southern backcountry in southern Georgia and northern Florida.

From Harper's New Monthly

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The epithet cracker has been applied in a derogatory way to rural, non-elite white southerners. Linguists now believe the original root to be the Gaelic craic, still used in Ireland (anglicized in spelling to crack) for "entertaining conversation."

Image from James Wells Champney

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Traditional poled boats, suited to maneuvering in tight water, were used in the days of alligator hunting and frog gigging. The swamp is now a federal wildlife refuge.

Courtesy of Zach S. Henderson Library, Georgia Southern University, Delma E. Presley Collection of South Georgia History and Culture.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Zach S. Henderson Library at Georgia Southern University.

The Okefenokee Swamp covers more than 700 square miles of southeast Georgia and northwest Florida. American Indians named the swamp "land of the trembling earth."

Courtesy of Explore Georgia, Photograph by Ralph Daniel.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to Explore Georgia.

During the 1800s the Okefenokee Swamp region had one of the smallest African American populations in the state. After the Civil War more Blacks were drawn to the area by jobs in farming, turpentining, logging, and the railroad industry.

Courtesy of Zach S. Henderson Library, Georgia Southern University, Delma E. Presley Collection of South Georgia History and Culture.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Zach S. Henderson Library at Georgia Southern University.

Folklorists have helped preserve the region's distinctive folk speech, tales, music, customs, home remedies, and beliefs.

Courtesy of Zach S. Henderson Library, Georgia Southern University, Delma E. Presley Collection of South Georgia History and Culture.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Zach S. Henderson Library at Georgia Southern University.

The swamp's distinctive ecosystem is the subject of legends, tall tales, and personal experience narratives about bears, alligators, and encounters with the natural world.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia, Photograph by Geoff L. Johnson.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to Explore Georgia.

First published in 1844, The Sacred Harp songbook has helped to promote the style of singing known as "Sacred Harp," "shape-note," or "fasola" singing.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

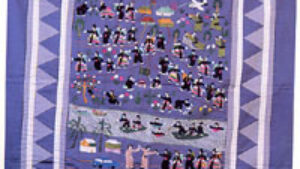

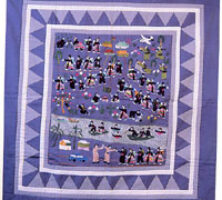

A story cloth by textile artist and Hmong refugee May Tong Moua depicts Hmong villagers fleeing Communist forces (upper right-hand corner) in Laos and crossing the Mekong River to arrive at a refugee camp in Thailand. A resident of Lilburn, May Tong Moua is among a number of Hmong refugees who resettled in DeKalb and Gwinnett counties. The story cloth, made in 1991, is housed at the Atlanta History Center.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Atlanta History Center.

Sugar cane grinds lent to the wiregrass region's occupational folklore as well as provided an opportunity for social gatherings.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, # clq103.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A rattlesnake is milked of its venom during a rattlesnake roundup in Fitzgerald, the seat of Ben Hill County, in 1974.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, # ben332.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

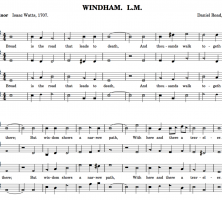

The shape-note system in The Sacred Harp uses a different shape to represent each of the four syllables in the musical scale: a triangle (fa), a circle (sol), a rectangle (la), and a diamond (mi).

The tune "Windham" as it appears in The Sacred Harp, 1911 edition. Image from Wikimedia.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The earliest raftsmen were farmers of the river valleys of the Altamaha River and its tributaries, the Oconee, Ocmulgee, and Ohoopee.

Courtesy of Delma E. Presley

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Since its opening in 1992, the play's impact has been felt around the nation as cast members share their art-based community revitalization experiences in other towns and states.

Courtesy of Swamp Gravy

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

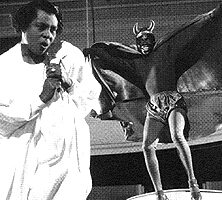

Performed in pantomime, the play Heaven Bound depicts the conflict between the pilgrims and Satan, who is the main character. Churchgoers make up the cast, which includes thirty-four players and ten pilgrims.

Courtesy of Gregory Coleman

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.