Mennonites are Christians whose origins can be traced back to sixteenth-century Anabaptists, a radical group of religious reformers who emerged in Switzerland during the Protestant Reformation. Mennonites arrived in America during the seventeenth century but did not establish a significant presence in Georgia until the twentieth century. As of 2007 more than 1,000 Mennonites lived in Georgia.

Beliefs and Doctrines

Mennonites derive their name from Menno Simons, a Catholic priest in Holland who, after joining the movement in 1536, unified and led scattered Anabaptists suffering persecution under various European authorities. As products of the Protestant Reformation, Mennonites share certain beliefs with Protestant Christians, including the authority of Christian scripture, salvation by faith, the nature of redemption, and the priesthood of the believer. However, like most of their Anabaptist forebears, they also espouse the ethic of nonresistance, a form of pacifism in which physical violence, including action taken in self-defense, is prohibited; believer’s baptism, in which adults, rather than infants, are baptized as a profession of faith; voluntary church membership; the separation of church and state; and religious tolerance.

Mennonites tend toward a literal interpretation of the Bible that often leads them to practice a rigorous form of communal discipleship that does not always conform with modern society. Many communities choose to adopt a rural, separatist lifestyle, and these groups also frequently restrict the use of modern technology, dress in traditional attire, and retain their native German language. In 2006 there were more than one million baptized members of Mennonite-related churches across the globe, with Africa holding a larger share than any other continent outside North America. Mennonite congregations usually associate with one other through participation in regional and national conferences.

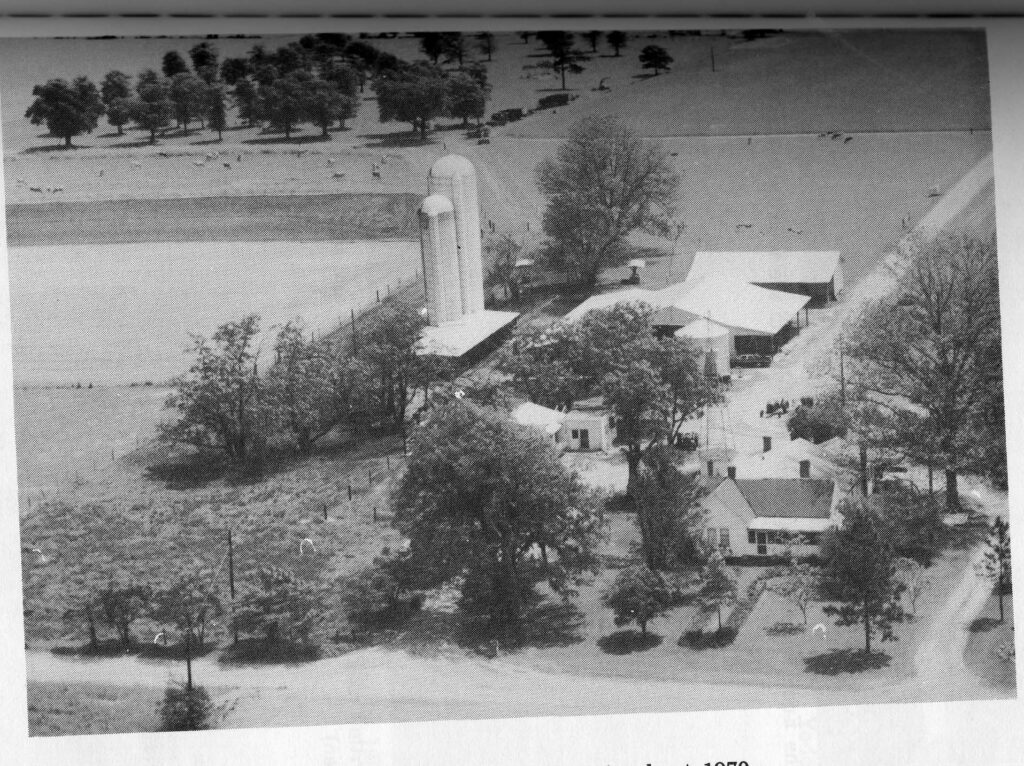

Photograph from The Amish Mennonites of Macon County, Georgia, by E. S. Yoder

History

A number of different historical influences have shaped Mennonite doctrine, polity, and piety since the denomination’s inception. For instance, internal schisms resulted in the creation of many different Mennonite groups; such rifts usually developed around ethics and degrees of nonconformity rather than around doctrine. In the 1690s, Mennonites suffered a major internal schism when a Swiss Mennonite bishop named Jakob Ammann called for stricter rules concerning attire, as well as more rigorous and systematic disciplinary measures. Ammann’s followers would later be known as Amish or Amish Mennonites. Later internal disputes among American Mennonites centered on the acceptance of new forms of technology and the adoption of such new religious trends as revivalism, Sunday schools, denominational institutions, and missions.

Migration patterns also contributed to the establishment of various Mennonite congregations through the years. As early as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Mennonites in Holland and northern Germany became largely separated from Mennonites in Switzerland and southern Germany. Dutch and north German Mennonites also followed trade routes to North America, arriving in New Amsterdam (later New York City) as early as the 1650s. Germantown, Pennsylvania, was the site of the first permanent Mennonite settlement in America; most of the immigrants settling there in 1683 came with the hope of escaping heavy taxes and bad economic conditions in Europe.

The nineteenth century saw increased immigration to North America from Mennonites originating in Switzerland, southern Germany, and Russia. Upon arrival, diverse Mennonite groups often assisted and associated with each other, but they tended to form settlements with co-religionists of the same ethnicity and cultural heritage. These communities began spreading west, north, and south as land opened up for ownership, and most settled in rural areas to engage primarily in farming.

The faith of Mennonites has also been shaped by periods of persecution. For instance, although North American Mennonites experienced relatively less persecution than their European predecessors, their ethic of nonresistance occasionally placed them at odds with American government and society. American Mennonites maintained somewhat amiable relations with government authorities during the wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but during World War I (1917-18) they were subject to the draft and forced to go to military camps, where some died of injuries inflicted upon them by soldiers opposed to their ethic of nonresistance. As a result, Mennonite leaders joined with other pacifist religious groups before World War II (1941-45) to plead with the government for an alternative to military service. The creation of the Civilian Public Service camps of the 1940s, where conscientious objectors could work under civilian direction in soil conservation, dam building, and other projects, resulted from this request.

Reprinted by permission of Mennonite Church USA Historical Committee

Mennonites in Georgia

The first Amish or Mennonite settlement in Georgia was established in Pulaski County in 1912. The second was founded two years later in Appling County by a group of Old Order Amish, a conservative branch of the Mennonite faith. This venture was largely unsuccessful, however, and all but one member of the community had moved away from the state by 1923.

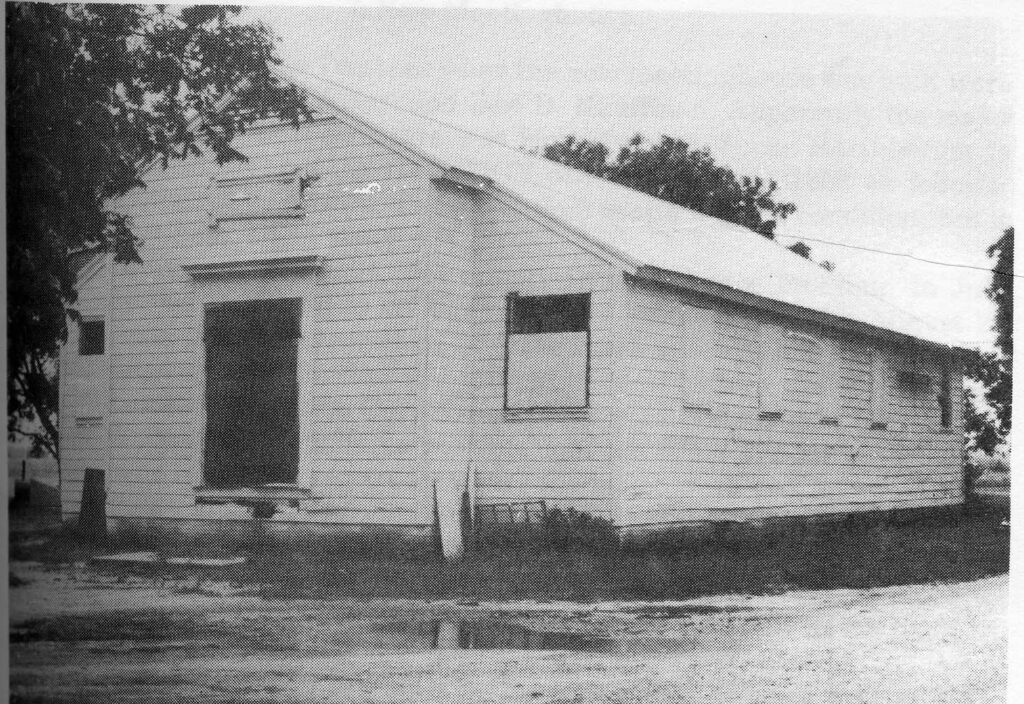

In 1953 a community of Beachy Amish Mennonites from Virginia formed a more permanent settlement, which thrives today near the town of Montezuma, in Macon County. Deriving their name from Moses M. Beachy, the sect’s first bishop, Beachy Amish Mennonites accept some technological conveniences that Old Order Amish prohibit, including automobiles and electricity. However, they still strive to maintain a separatist posture in relation to American society, rejecting such modern forms of entertainment as movies and television. As of 2007 the community in Montezuma supported three churches and three Mennonite schools. The White House Farm Bed and Breakfast and the Deitsch Haus restaurant, both operated by the Yoder family in Montezuma, offer visitors a glimpse of life in a Mennonite community.

Soon after the Montezuma community was established, another group of Mennonites settled in Louisville, in Jefferson County, in 1953, and the following year another community was founded in Colquitt, in Miller County.

Photograph from The Amish Mennonites of Macon County, Georgia, by E. S. Yoder

In 1958 a Mennonite service unit was founded in Atlanta by missionaries Hershey and Norma Leaman. This unit coordinated various outreach activities, including the placement of draft-age Mennonite men in civilian service organizations during the Vietnam War (1964-73), and established Berea Mennonite Church. Still in operation today, Berea Mennonite Church claims to be one of the first racially integrated churches in Atlanta.

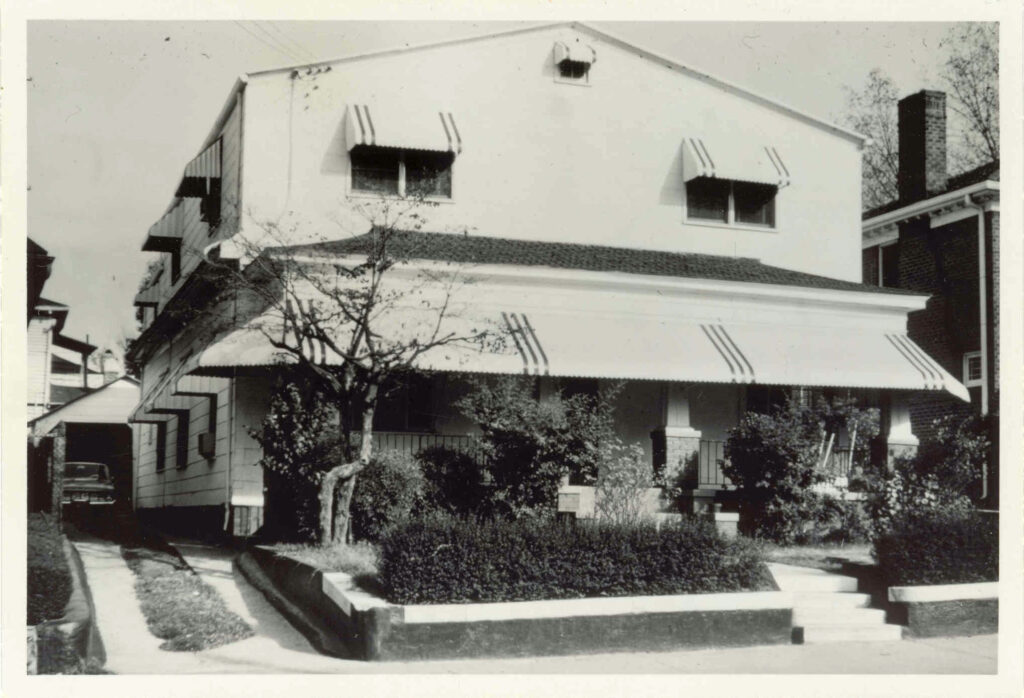

Another entity, the Mennonite House, operated in Atlanta from 1961 to 1964. Established by Mennonite minister Vincent Harding and his wife, Rosemarie, of Chicago, Illinois, this house on Houston Street (later renamed John Wesley Dobbs Avenue, in honor of influential Black political leader John Wesley Dobbs) became a residence and headquarters for Mennonites active in the civil rights movement. In 1962 Vincent Harding was arrested at a demonstration in Albany during the Albany Movement, prompting internal debate over appropriate protest activities for Mennonites. The Hardings ultimately left Mennonite House in 1964.

Since the 1950s various other Mennonite groups have started churches in Georgia, and by 2007 there were twenty-two congregations in the state. Several of these communities also support schools, including Meadow View Mennonite School in Gordon County, Meigs Mennonite Christian School in Mitchell County, Pinecrest Mennonite School in Jefferson County, and Waynesboro Mennonite School in Burke County. Two of these congregations, located in Americus and Atlanta, are affiliated with the Southeast Mennonite Conference of the Mennonite Church USA, which in 2003 held its biennial convention in Atlanta.

Reprinted by permission of Mennonite Church USA Historical Committee