Cecil Alexander was a prominent Atlanta architect and civic leader. As a partner in the architectural firm FABRAP, he was responsible for some of the city’s most notable public buildings. During the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s, he was a leader in the movement to peacefully desegregate the city’s public housing and local businesses. He also designed a new state flag that removed one of the last symbols of Georgia’s racially divided past.

Reprinted by permission of Stephen H. Moore (http://www.shmoore.com/)

Early Life

Cecil Abraham Alexander Jr. was born in Atlanta on March 14, 1918, the only son of prosperous Jewish parents, Julia Moses and Cecil A. Alexander. The family lived in the Virginia Highland neighborhood of Atlanta. His father was the owner of J. M. & J. C. Alexander’s Hardware in Atlanta, which is reputed to have been the model for Scarlett O’Hara’s store in the novel Gone With the Wind (1936).

After graduating from high school, Alexander enrolled in 1936 at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he spent one year before being accepted to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. He earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture at Yale, then continued graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. In 1941 he entered Civilian Pilots Training, a program established by U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt to create a backlog of pilots who would be available if the country became involved in World War II (1941-45). Around this time, Alexander met a couple who had fled Nazi Germany and who told him firsthand of the horrors that Jews in Germany, Poland, and Austria faced. He decided then that he wanted to fight the Nazis even though the United States had not yet formally gone to war.

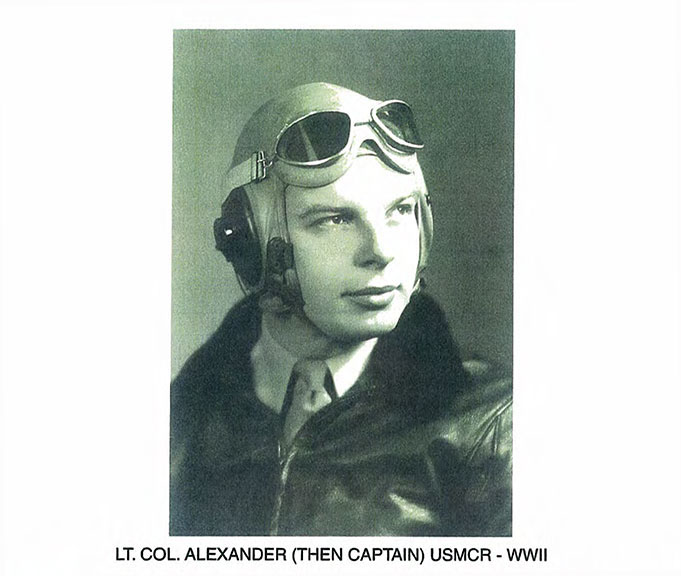

Military Service

After obtaining a commercial pilot’s license, Alexander interrupted his studies to enlist in the navy with the aim of becoming an aviator. While he was in flight training school, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the United States subsequently entered World War II. As part of the top 10 percent of naval aviators, Alexander volunteered for the marines and became a dive bomber pilot. Before shipping out for the Pacific, he married Hermione Weil of New Orleans, Louisiana. They eventually had three children.

Courtesy of Cecil Alexander

During fifteen months of service, Alexander flew a total of sixty missions and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross twice. As a decorated veteran returning to the states, he had a bright future ahead of him. In 1946 he enrolled in the graduate architecture program at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he studied with Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus school, which was a major influence on the development of modern architecture. After earning his degree, Alexander worked in New York City as an architect. Soon he and his wife returned home to Atlanta, where he began what would be a long and distinguished career in what was rapidly becoming the economic heart of the South.

Fighting for Equality

As his practice thrived, he also became an active participant in the civic and political life of Atlanta during the 1950s. He was appointed by Mayor William B. Hartsfield to chair the Citizen’s Advisory Committee for Urban Renewal. Assembling the most powerful business, civic, and religious leaders from the Black and white communities, the committee launched a program to e liminate slum housing and replace it with low-income public housing.

Courtesy of AT&T

With Hartsfield’s retirement in 1961, businessman Ivan Allen Jr. defeated Lester Maddox to win the mayor’s office. Progressive and reform-minded, Allen tapped Alexander to head a variety of programs designed to move the still-segregated city toward racial equality.

Alexander became a prominent face of the campaign against segregation, appearing frequently on television and in newspaper headlines. As chair of the Allen administration’s Housing Resources Committee, he mobilized the construction of more than 22,000 low-income housing units to replace slums throughout the city. He guided the Committee to Mediate Racial Unrest and formed the Atlanta Black Jewish Coalition with civil rights leader (and later U.S. congressman) John Lewis. He was also one of the organizers of a dinner to honor Martin Luther King Jr. after King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

After his wife was killed by a drunk driver in 1983, Alexander launched a program to educate young people about the dangers of drinking and driving. He also campaigned for tougher laws to combat drunk driving. In 1985 he married Helen Eisemann.

Architectural Career and Leadership

In 1948 Alexander and Bernard Rothschild founded the Alexander and Rothschild architectural firm, and two of their early projects were published in Architectural Record: the fully air-conditioned Peachtree-Seventh Building (circa 1949-50, later Atlanta Federal Building and then Peachtree Lofts) and the Peachtree Baker Building (circa 1956). During this period Alexander also served periodically as a design critic for the Georgia Tech Architecture School.

Photograph by David A. Pike

The firm merged in 1958 with Finch Barnes and Paschal to form FABRAP. As principal with FABRAP, Alexander worked on such high-profile projects as the corporate headquarters for the Coca-Cola Company (1970, 1979, 1981), Southern Bell (later BellSouth, 1980), and Georgia Power Company, as well as the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium (1965, razed 1997). In addition to commercial structures he also designed a number of prominent homes, including a futuristic “round house” (1958) located on Mt. Paran Road in Atlanta, which was nominated for the National Register of Historic Places.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Following his retirement from full-time architectural practice with FABRAP in 1985, Alexander collaborated with architect John Portman, a relationship that continued through the 1996 Olympic Games. He also continued to campaign for racial equality. One of his goals was to replace Georgia’s 1956 state flag and its prominent Confederate symbolism. As Atlanta prepared to host the 1996 Olympics, he created a new flag design that incorporated images from all of Georgia’s historic flags. His design proposal was ill received by legislators, but in 2000 Alexander met with Governor Roy Barnes. Barnes supported Alexander’s design, with minor changes, and urged lawmakers to adopt it. By early 2001 a new state flag had been approved by the Georgia General Assembly and was flying over the statehouse. Controversial from the start, the new flag proved to be highly unpopular among Confederate heritage supporters. It was replaced three years later with another design, which ended the controversy.

Reprinted by permission of Stephen H. Moore (http://www.shmoore.com/)

Alexander has received the America Institute of Architects’ Whitney M. Young Jr. Award for improving race relations, the Ivan Allen Award for community service, and the Yale Medal for distinguished alumni. The novelist Pat Conroy has said that Alexander was the model for the character of Colonel Hudspeth in The Great Santini (1976).

Alexander died in Atlanta on July 30, 2013, at the age of ninety-five.