The field of decorative arts encompasses ceramics, furniture, glass, metalwork, and textiles. Decorative arts offer a reflection of their makers’ and owners’ ways of life and include such functional, everyday objects as wooden chairs, silver spoons, cotton quilts, and stoneware jugs.

In Georgia, decorative arts are shaped by settlement patterns, cultural influences, availability of materials, and changing fashions. Therefore, decorative arts made and used in Georgia vary greatly over time and throughout the state. Though extensive research remains to be conducted in this field, numerous intriguing objects exist in public and private collections, and many makers, including quilter Harriet Powers from Athens, cabinetmaker Peter Miller from Savannah, and the Meaders family of potters from Mossy Creek, are widely known.

Southern decorative arts did not receive serious scholarly attention until the 1960s. The first publication to examine furniture in Georgia was Henry D. Green’s Furniture of the Georgia Piedmont before 1830, which was written for a 1976 exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Since that time only a few other large-scale exhibitions featuring Georgia’s decorative arts have been presented, including “Neat Pieces: The Plain-Style Furniture of Nineteenth-Century Georgia” at the Atlanta Historical Society in 1983-84, “Georgia’s Legacy: History Charted through the Arts” at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens in 1985, and “Hidden Heritage: Recent Discoveries in Georgia Decorative Art, 1733-1915” at the High Museum of Art in 1990. Preceding “Hidden Heritage,” the National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the State of Georgia sponsored the Georgia Decorative Arts Survey, which documented approximately 4,300 objects from across the state. That survey, conducted between 1986 and 1989, is located at the Henry D. Green Center for the Study of the Decorative Arts at the Georgia Museum of Art.

Regions and Materials

Georgia’s decorative arts often are categorized by region: Tidewater, Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and Highlands. The small Tidewater region includes the barrier islands and the low-lying areas of the mainland along the coast. The Tidewater is sometimes grouped with the large Coastal Plain region, which encompasses the land between the Tidewater and the fall line. The Piedmont, a region that has produced a high percentage of Georgia’s decorative arts, runs from the fall line, through hills and valleys, to the Highlands in the upper part of the state. The small Highlands region features the southern tip of the Blue Ridge Mountains. These regions were settled at different times in the state’s history, due in part to the difficulties both of travel during Georgia’s early years and of negotiations with Native American peoples for land ownership. Coastal areas, and areas easily reached by river, were typically the first settled and therefore the first to have decorative arts. The rocky lands of the Highlands were the last to be settled in the state.

Craftsmen in Georgia often used local materials when making decorative arts. Such native woods as birch, cedar, cherry, chestnut, cypress, hickory, maple, tulip poplar, walnut, and yellow pine are often found in the furniture built in Georgia. Potters established potteries in areas where the raw materials, including clay, wood, and sand, needed to make their wares were readily available. Coastal basket makers, using traditional African methods, often made coiled baskets from the reeds and grasses collected near rivers and the coast.

Forms

Decorative arts made in the state’s early settlements often exhibit characteristics that reflect the makers’ countries of origin. For example, a table in the collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, reveals the maker’s Germanic background through its decorative characteristics (such as outwardly turned legs and flat stretchers, or bars, between table legs) and its construction. The table was made around 1740 in Ebenezer, a Salzburger settlement located upriver from Savannah. Examples from other parts of Georgia illustrate the influence of African, English, French, and Spanish craftsmen and designers.

Furniture

One form of furniture often associated with Georgia is the huntboard. For much of the twentieth century, the term was used to describe a serving table that contains drawers and is generally taller and shallower than traditional sideboards (used in dining rooms for serving food and displaying silver). The traditional explanation for the name “huntboard” is that the piece was used outdoors to serve food before or after a hunt. “Huntboard,” however, does not appear in written records from the nineteenth century, and the term and explanation likely originated in the early twentieth century. Many scholars believe that this furniture form originally was grouped with sideboards or slabs (tables), both of which are similar to it in form. The height common to this form and many others found throughout the South may be an indicator of the typical ceiling height in southern homes.

Other forms closely associated with the South in general and Georgia in particular are the lazy-Susan table (a dining table with a revolving center tray), the cellaret (a small chest used to store bottles of wine or liquor), the sugar chest (a small chest, often on legs, with bins for such items as sugar, coffee, and spices), and the hide-bottomed slat-back chair (a simple chair with a flat, slatted back arranged like a ladder and a seat made from animal hide).

Textiles and Needlework

Textiles in Georgia usually reflected national trends, both in style and materials, although future research may reveal distinct regional characteristics. Imported fabrics and machine-woven fabrics were increasingly available in Georgia, particularly in Savannah, during the nineteenth century. Pieced and appliquéd quilts and woven coverlets, because they are handmade, are unique even when closely related to national fashions. Some of the national trends embraced by women in the state include the making of friendship and album quilts in the 1840s and 1850s and crazy quilts in the late nineteenth century.

Schoolgirl needlework, most commonly found in the form of stitched samplers or embroidered pictures, was popular in the United States during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In the past, scholars paid little attention to Southern schoolgirl needlework and frequently believed that little, if any, was made in Georgia. Ongoing research, however, is uncovering numerous examples.

Ceramics

Ceramics made in Georgia during the nineteenth century were predominately functional vessels, usually intended for food storage and made of alkaline-glazed stoneware. Many potters came from pottery centers in North Carolina and from South Carolina’s Edgefield District, and they brought the practices and styles of those places with them. Other ceramic forms found in the state include grave markers and face jugs. Face jugs originally were closely associated with Africans and African Americans in the South. Today many potters, including the Hewell family and Michael and Melvin Crocker in northeast Georgia, continue to practice traditional methods of turning pots.

Neoclassical

Neoclassical design was popular in Georgia, as well as in the rest of the country, at the end of the eighteenth century and during the first few decades of the nineteenth century. The design is characterized by the use of classical Greek and Roman forms and motifs, such as fluted columns, acanthus leaves, eagles, swags, and urns. The young nation embraced this style for its architecture and decorative arts, partially because it provided visual connections between the world’s oldest and newest democracies. Neoclassical design is sometimes divided into two styles, the earlier Federal style, characterized by light forms and surface decoration, and the later Empire style, with heavier forms and carved, sculpted decoration.

Early-nineteenth-century cabinetmakers residing in Georgia’s larger towns produced high-quality furniture and other objects in the neoclassical style. Access to printed stylebooks (collected drawings of various furniture forms and details), importation of new objects, and an influx of artisans trained in the latest styles offered the residents of such towns as Savannah and Augusta immediate contact with up-to-date national and international fashions.

In the port city of Savannah, wealthy citizens often chose to decorate their homes with stylish goods imported from New York City rather than with locally crafted objects. Cabinetmakers there had ready access to imported woods, including mahogany, which they used as the primary woods and veneers in their furniture. Decorative arts in Augusta from this time often show the influence of design trends in Charleston, from which many of its settlers came. As the terminus of the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia—a major route for colonists who wanted to settle the frontier—Augusta also experienced the influences of styles from points further north along that road.

In smaller towns, removed from the large style centers, neoclassical design appeared in simpler forms. For example, instead of delicate inlaid designs on furniture, rural furniture makers often used more basic methods, such as painted designs. The differences between the high-style decorative arts demanded by wealthy customers in cities and the homemade, vernacular decorative arts made in rural areas remained strong in some parts of the state into the early twentieth century.

The importation of goods has affected the decorative arts in Georgia since the first settlers arrived with goods from their homelands. Imported goods certainly played a large role in influencing the design of objects made in Georgia, and the question of which objects were imported versus which were made in the state has yet to be answered.

This question is particularly pertinent when considering silver. The earliest silversmiths in Georgia worked in Savannah and Augusta, the state’s first centers of trade. Often they advertised not only as silversmiths, but also as jewelers and watchmakers. Many silver shops carried wares imported from New England and New York City in addition to locally made wares, while others functioned solely as retailers of imports. All of these wares were marked with the name of the shop where they were sold, leading to difficulty today in determining an object’s origin. The silver made in Georgia during the nineteenth century is stylistically similar to silver made elsewhere in the country and reflects popular national styles, including neoclassical, Renaissance revival, and rococo revival.

Victorian

During the Victorian Era (1837-1901) Georgia continued to grow. New towns were established, railroads were built, and industry evolved. With the increasing ease of travel, ideas about design in the decorative arts spread more quickly, and as technology evolved, decorative arts were made more quickly. Cabinetmakers continued a shift begun earlier in the century, from the practice of one craftsman constructing an object from start to finish, to the practice of many craftsmen, each with a specialized job, working together in larger shops. The era saw a mix of revival styles, including Gothic revival, Renaissance revival, and rococo revival. Many of the decorative arts made in Georgia during this time echo the decorative arts seen throughout the nation, and fewer regional characteristics are obvious, although some do exist, particularly in rural areas.

One notable trend in the late nineteenth century, both in the state and in the nation, was china painting. This practice, which involved decorating unpainted porcelain vases, plates, pitchers, and other forms related to dining and decoration, was especially popular among well-to-do women. William Lycett, whose father was a noted figure in the field of ceramics, established a china-painting studio in Atlanta in 1883. He provided instruction in china painting to amateurs and employed professional decorators to embellish imported porcelain blanks. Painted porcelain wares marked with Lycett’s name are present in many historic homes and collections across the state.

The most famous Georgia quilter from the Victorian Era is Harriet Powers, who was born enslaved in the Athens area. Only two of her quilts survive, one in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and the other in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. Both quilts were made after emancipation and both use appliquéd images to depict biblical stories mixed with astronomical events.

Arts and Crafts

The Arts and Crafts Movement, which began in England in the late nineteenth century, reached its height in the United States by the early twentieth century. The movement was a reaction against the poor craftsmanship, rough working conditions, and cluttered revival styles brought on by the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution. Objects created in the Arts and Crafts style look back to the handcrafted guild practices of medieval production and typically feature details indicating handwork (such as hammered surfaces on metal), stylized motifs from nature, and simple, natural materials that offer their own colors and textures as ornamentation.

The crafts made at Tallulah Falls School, which was established in the Blue Ridge Mountains by the Georgia Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1909, were strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement. Textiles made by female students there ranged from woven coverlets in traditional Appalachian patterns (typically geometric patterns in two or three colors) to three-part screens with woven views of the local landscape. Female students also made baskets from local broom sedge, raffia, and pine needles, as well as fans with feathers from local turkeys, white geese, peacocks, and guinea hens. Male students used wood from native rhododendron bushes to build rustic furniture. The height of handicrafts production at Tallulah Falls School lasted from about the 1910s through the 1940s.

Crafts made at Berry College, founded near Rome in 1902 by Martha Berry, had practical applications. Boys worked in the woodshop to produce furniture that was used throughout the campus. Much of the handicrafts training for girls centered on weaving, which would benefit their future domestic environments, a fact that also influenced some of the activities at Tallulah. The crafts made at Berry initially included baskets woven of honeysuckle or pine needles, fans made of goose or peacock feathers, and corn-shuck rugs. After other crafts were discontinued, weaving remained a profitable activity and is still practiced by students at Berry today. Most of the items woven at Berry employ traditional weaving patterns, while others feature designs based on local imagery, including log cabins, dogwood flowers, pine cones, and violets.

Colonial Revival

During much of the twentieth century, particularly between World War I (1917-18) and World War II (1941-45), the colonial revival style was popular in American decorative arts. The style emphasized traditional American handicrafts and encouraged designs and objects for the home that were suggestive of life in early America. In Georgia, this style often overlaps with the earlier Arts and Crafts style. Common objects from this period include hooked rugs, wrought-iron candle holders, and printed fabrics with images of carriages and oil lamps.

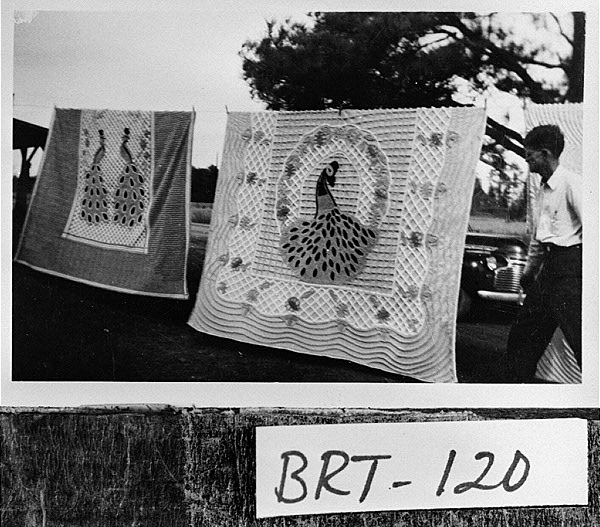

One Georgia textile form that is closely associated with the Colonial Revival style is the chenille bedspread, or hand-tufted bedspread. For about the first half of the twentieth century, the production of chenille spreads was centered in northwest Georgia along the Dixie Highway, known in the Dalton area as “Bedspread Boulevard” or “Peacock Alley” because of the popular peacock motif used on the spreads. The practice of hand tufting was rooted in the late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century techniques of making candlewick spreads (bedspreads featuring a raised decoration created either with actual candlewicks or with a soft yarn resembling candlewicks).

Catherine Evans Whitener of Dalton is credited with reviving the hand-tufting tradition in the 1890s. The chenille bedspreads appeared first in white, then in vibrant colors, and were often sold along the roadside to Florida-bound tourists. As the highway grew and national marketing of the spreads expanded, mechanized production replaced hand tufting. The mechanization of chenille spreads ultimately led to the tufted carpet industry, which is still centered in Dalton.

Studio Craft Revival

Following World War II, such studio craft traditions as ceramics, glass, metals, textiles, and wood experienced a burst of activity across the United States as veterans returned to school on the G.I. Bill. Art departments in colleges and universities expanded and offered numerous opportunities for students to work with these materials. No longer bound by the need to produce functional objects, a need that was being met by industry and mass production, postwar artisans explored the expressive and decorative potentials of their media.

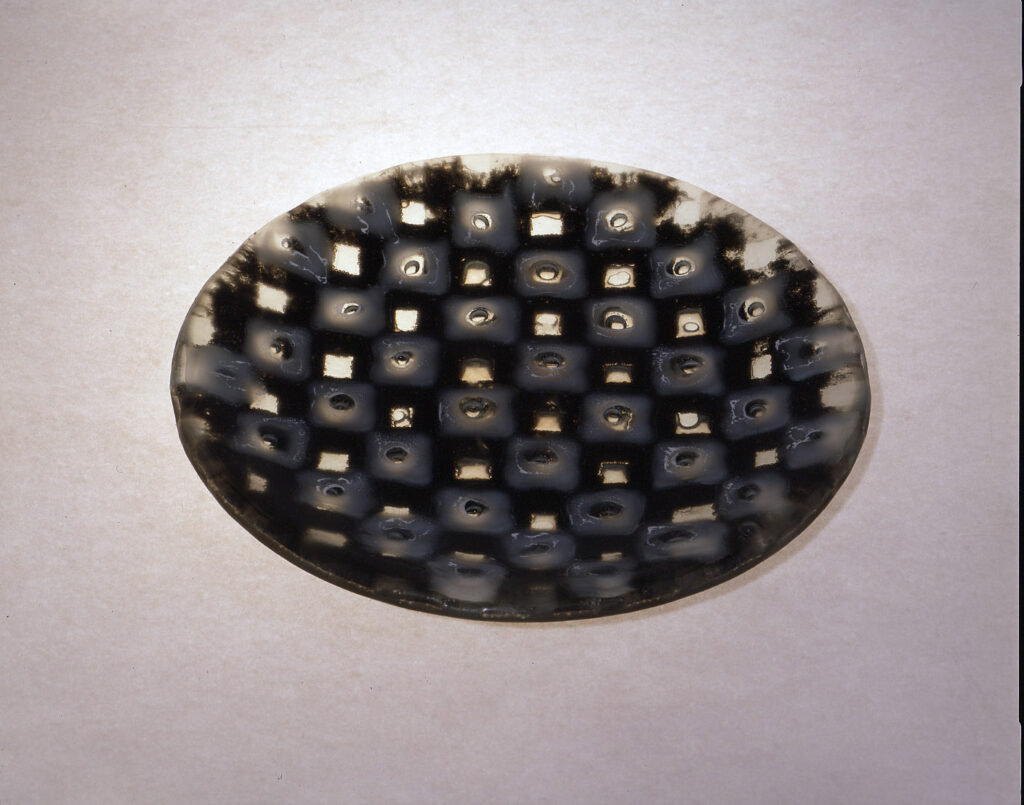

Two craftspeople associated with the University of Georgia, Ann Orr and Earl McCutchen, emerged as important artists in this field. Orr created handwrought vessels and jewelry in silver and copper that reflected the simple lines and forms of Scandinavian modern design. McCutchen worked in both ceramics and glass. With his ceramic vessels he experimented with local clays and unusual methods of glaze application. With glass, he created unique laminated and slumped (heated until the sheet of glass softens and conforms to a mold) plates and bowls that incorporated unexpected materials, including paper, aluminum foil, and chicken wire, sandwiched between layers of glass. Subsequent craft artists to gain national recognition while working in Georgia are Ed Moulthrop, Andy Nasisse, and Gary Noffke.