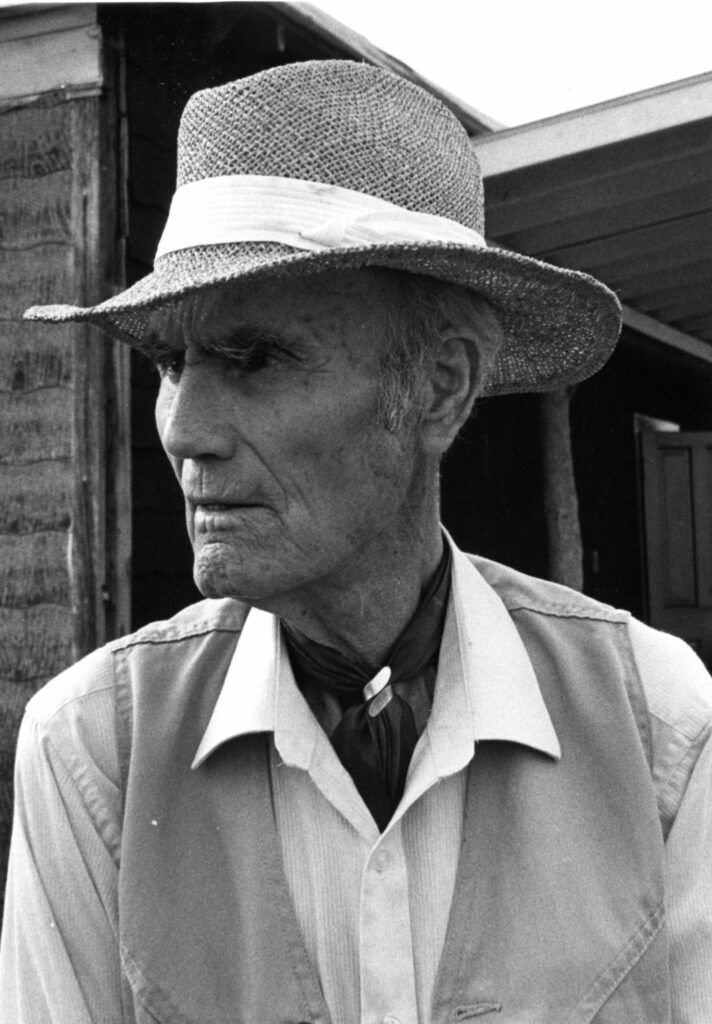

A native of north Georgia, Don West achieved success as one of the foremost southern regional poets of the twentieth century. He was at different times a labor organizer, political radical, preacher, progressive educator, and outspoken spokesperson for human equality in the generation before the civil rights movement. Although he is best known for his literary works, West was also an effective proponent of the Social Gospel, embraced by some of the South’s most dedicated religious reformers.

Early Life

Born in 1906 in Devil’s Hollow, near Ellijay in Gilmer County, Donald L. West grew to young adulthood in the north Georgia mountains. The eldest son of a farmer, he took pride in the independent spirit that had made his forebears nonconformists who opposed slavery in the antebellum years. This heritage of independence expressed itself in West’s career, during which he often found himself at odds with the folkways and beliefs of the communities in which he lived and worked. Throughout his life he remained committed to a progressive view of ethnic and racial harmony, which linked him with his personal family history.

After his family moved to the lowlands as sharecroppers, West enrolled in 1923 at the Berry School in Rome, a school for impoverished children from the north Georgia mountains. During his senior year at Berry, he organized a protest when the racist film Birth of a Nation was shown on campus. West was expelled for his part in the protest, and he left the institution without a diploma. After working for a telephone company for a short time, he enrolled at Lincoln Memorial University (LMU) in Tennessee, where he met and married Mabel Constance “Connie” Adams. Expelled from LMU for leading a protest against campus paternalism, the popular West was reinstated and graduated in the class of 1929.

Early Career

After graduation West enrolled at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he entered the Divinity School to pursue a calling to preach. There he came under the influence of the professors Alva Taylor and Willard Uphaus, both staunch proponents of the Social Gospel, a religious perspective that meshed well with West’s own beliefs. During his Vanderbilt years West embraced socialism and began working in the labor movement. He was involved with the 1929 Gastonia, North Carolina, textile strike, and in 1932 he was a labor organizer in the bitter miner’s strike at Wilder, Tennessee.

In 1931, the year he received his degree from Vanderbilt, he also published his first volume of poetry, Crab-Grass, which celebrated the mountain culture and working people of the South.

As a student West visited the Danish folk schools inspired by N.F.S. Grundtvig, who advocated a curriculum based on folk tradition and cultural heritage. Imbued with the folk school philosophy, in 1932 he collaborated with Myles Horton to establish the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. After less than a year at Highlander, West broke with Horton and returned to Georgia, where he established the Southern Folk School and Libraries in Kennesaw and immersed himself in political and labor organizing. Working closely with members of the Communist Party, West assumed a leadership role in the defense of the labor organizer Angelo Herndon, an African American in Atlanta who had been convicted under the Georgia insurrection law in January 1933. Pursued by antilabor authorities, West slipped out of Georgia in 1934 to continue his work as a labor organizer. From 1936 to 1937 he served as organizational director for the Kentucky Workers Alliance, a militant organization for the unemployed.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s West served Congregational churches in Bethel, Ohio, and Meansville, Georgia, where his literary work, often published in radical journals, became controversial and led to his resignation. In 1942 he became a teacher and school superintendent in Lula in Hall County, where he gained a national reputation as a proponent of cooperative, community-based learning. He received a Rosenwald Fellowship and left Lula in 1945. After a year of study, West accepted a position at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. At Oglethorpe he taught creative writing and continued his own literary work, publishing what is considered to be his finest work, Clods of Southern Earth, in 1946. This volume, a strong statement of Appalachian regionalism that emphasized the experience of working people, found a wide audience beyond the intellectual community.

Red-baited ruthlessly by the Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill and others, West left Oglethorpe in 1948 after a controversial defense of Rosa Lee Ingram, an African American defendant in a high-profile murder case, and involvement in the presidential campaign of the liberal Henry Wallace. In 1955, while editing a religious newspaper, The Southerner, in Dalton, he was again attacked for his labor activism and political affiliations. Subsequently, in 1957 he was forced to testify on his political activities before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1958 the House Committee on Un-American Activities called him as a witness at their Atlanta hearings, but West left without taking the stand.

Late Career and Legacy

By 1960 the Wests were teaching in Baltimore, Maryland, where they saved enough to invest in the establishment of the Appalachian South Folklife Center at Pipestem, West Virginia. Founded in 1964 and dedicated to the preservation of mountain culture and its tradition of self-respecting independence, the new institution attracted college students, activists, folk artists, and other Appalachian residents. At Pipestem in the 1960s and 1970s, West became a mentor for nonsectarian leftists and served as a link between the old and new radicalism. For the remainder of his life, he continued his writing and teaching, emphasizing the preservation of Appalachian values and resistance to the corrosive forces of industrialism. The Folklife Center, together with his poetry, remains as his living legacy to future generations. West died in Charleston, West Virginia, on September 29, 1992.