Flannery O’Connor is considered one of America’s greatest fiction writers and one of the strongest apologists for Roman Catholicism in the twentieth century. Born of the marriage of two of Georgia’s oldest Catholic families, O’Connor was a devout believer whose small but impressive body of fiction presents the soul’s struggle with what she called the “stinking mad shadow of Jesus.”

Early Life and Education

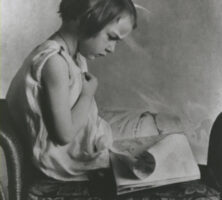

Mary Flannery O’Connor was born in Savannah on March 25, 1925, to Regina Cline and Edward F. O’Connor. She began her education in the city’s parochial schools. After the family’s move to Milledgeville in 1938, she continued her schooling at the Peabody Laboratory School associated with Georgia State College for Women (GSCW), now Georgia College and State University. When she was fifteen, O’Connor, an only child, lost her father to systemic lupus erythematosus, the disease that would eventually take her own life at age thirty-nine. Devastated by the loss of this close relationship, O’Connor elected to remain in Milledgeville and attend GSCW as a day student in an accelerated three-year program.

Courtesy of Ina Dillard Russell Library, Georgia College and State University

An avid reader and artist, she served as editor of the Corinthian, GSCW’s college literary magazine, and as unofficial campus cartoonist. O’Connor provided cartoons for nearly every issue of the campus newspaper, for the college yearbook, and for the Corinthian, as well as for the walls of the student lounge. The 2012 release of a collection of her cartoons Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons, renewed attention to her work in both linoleum cuts and pen and ink. Most significant, she contributed fiction, essays, and occasional poems to the Corinthian, demonstrating early on her penchant for satire and comedy. A social science major with a number of courses in English, O’Connor is remembered by her classmates as obviously gifted but extremely shy.Her closest friends recall her sly humor, her disdain for mediocrity, and her often merciless attacks on affectation and triviality.

In 1945 O’Connor received a scholarship in journalism from the State University of Iowa (now the University of Iowa). In her first term, she decided that journalism was not her metier and sought out Paul Engle, head of the now world-famous Writers’ Workshop, to ask if she might enter the master’s program in creative writing. Engle agreed, and O’Connor is now numbered among the many fine American writers who are graduates of the Iowa program. While there she got to know several important writers and critics who lectured or taught in the program, among them Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, Austin Warren, and Andrew Lytle. Lytle, for many years editor of the Sewanee Review, was one of the earliest admirers of O’Connor’s fiction. He later published several of her stories in the Sewanee Review, as well as critical essays on her work. Engle years after declared that O’Connor was so intensely shy and possessed such a nasal southern drawl that he himself read her stories aloud to workshop classes. He also asserted that O’Connor was one of the most gifted writers he had ever taught. Engle was the first to read and comment on the initial drafts of what would become Wise Blood, her first novel, published in 1952.

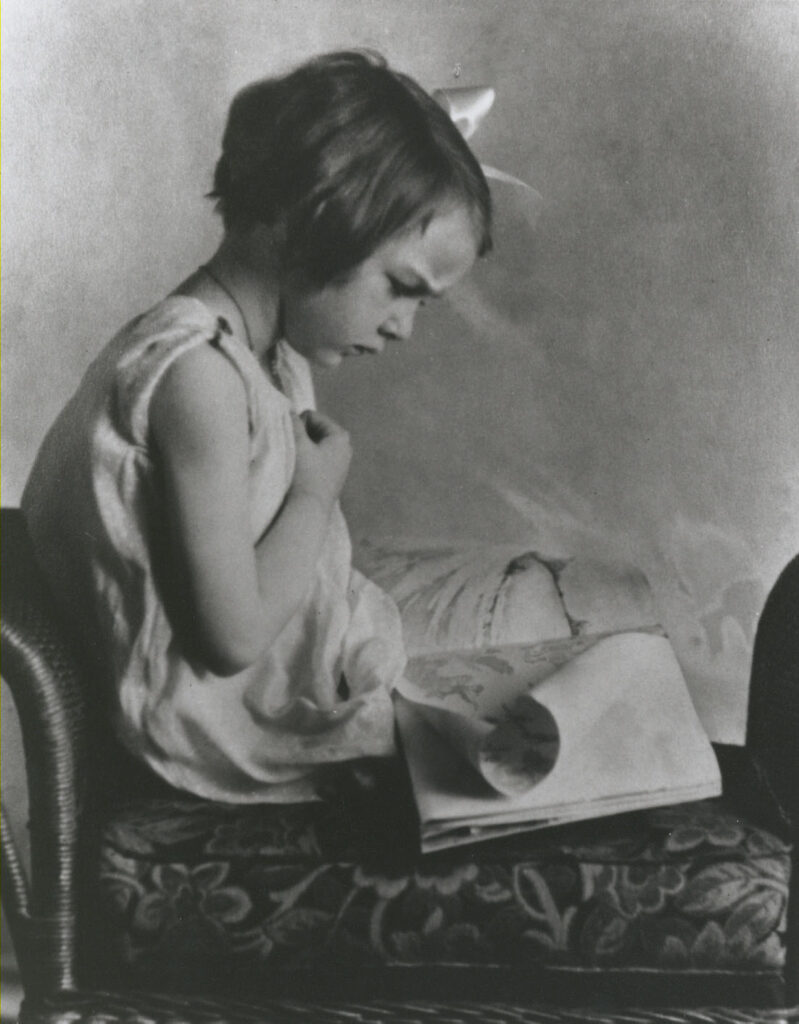

Courtesy of Ina Dillard Russell Library, Georgia College and State University

O’Connor’s master’s thesis was a collection of short stories entitled The Geranium, the title work having already become her first published story (Accent, 1946). Most stories in this collection, however, are the work of an apprentice in search of her own territory and voice; they suggest only faintly the sharp wit, finely honed style, and spiritual scope of O’Connor’s mature work. “The Turkey” most genuinely represents the significant connection between language and belief that came to pervade O’Connor’s work. This story also reveals her ear for southern dialect and marks one of her first attempts at the literary irony for which she later became famous.

Late Career

Following the completion of her M.F.A. in 1947, O’Connor won the Rinehart-Iowa Fiction Award for a first novel (for her submission of a portion of Wise Blood) and was accepted at Yaddo, an artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York. There she continued to work on the novel and became friends with the poet Robert Lowell. In 1949, after several months at Yaddo and some time in New York City and Milledgeville, O’Connor moved into the garage apartment of Sally and Robert Fitzgerald in Ridgefield, Connecticut, where she boarded for nearly two years. In the Fitzgeralds, O’Connor found devout Catholics who provided her with the balance of solitude and communion necessary to her creativity and her intellectual and spiritual life.

This stabilizing and productive time was interrupted in 1950, however, when O’Connor was stricken with lupus, the incurable, autoimmune disease that was then treated only by the use of steroid drugs. O’Connor survived the first life-threatening attack, but she was forced to return to Milledgeville permanently. Remaining in this historic central Georgia town for the rest of her life, from 1951 until 1964, O’Connor lived quietly at Andalusia, the family farm just outside town. In spite of the debilitating effects of the drugs used for treating lupus, O’Connor managed to devote a good part of every day to writing, and she even took a surprising number of trips to lecture and read from her works.

A prolific and devoted correspondent, O’Connor stayed in touch with the literary world through letters to the Fitzgeralds, Robert Lowell, Caroline Gordon, and others. It was, in fact, through letters that O’Connor came to know Gordon, who offered invaluable suggestions about her writing, especially about Wise Blood. O’Connor also took time to respond to letters from younger writers, to review works of theology for the Georgia Bulletin (a publication of the diocese of Atlanta), to tend her growing number of peacocks, and to receive visitors seeking advice on matters both literary and spiritual. During this time, O’Connor won numerous awards, among them grants from the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the Ford Foundation, a fellowship from the Kenyon Review, and several O. Henry awards.

An early 1964 surgery for a fibroid tumor reactivated O’Connor’s lupus, which had been in remission, and her health worsened during the following months. On August 3, 1964, after several days in a coma, she died in the Baldwin County Hospital. She is buried beside her father in Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville. At the time of her death, the Atlanta Journal observed that O’Connor’s “deep spirituality qualified her to speak with a forcefulness not often matched in American literature.”

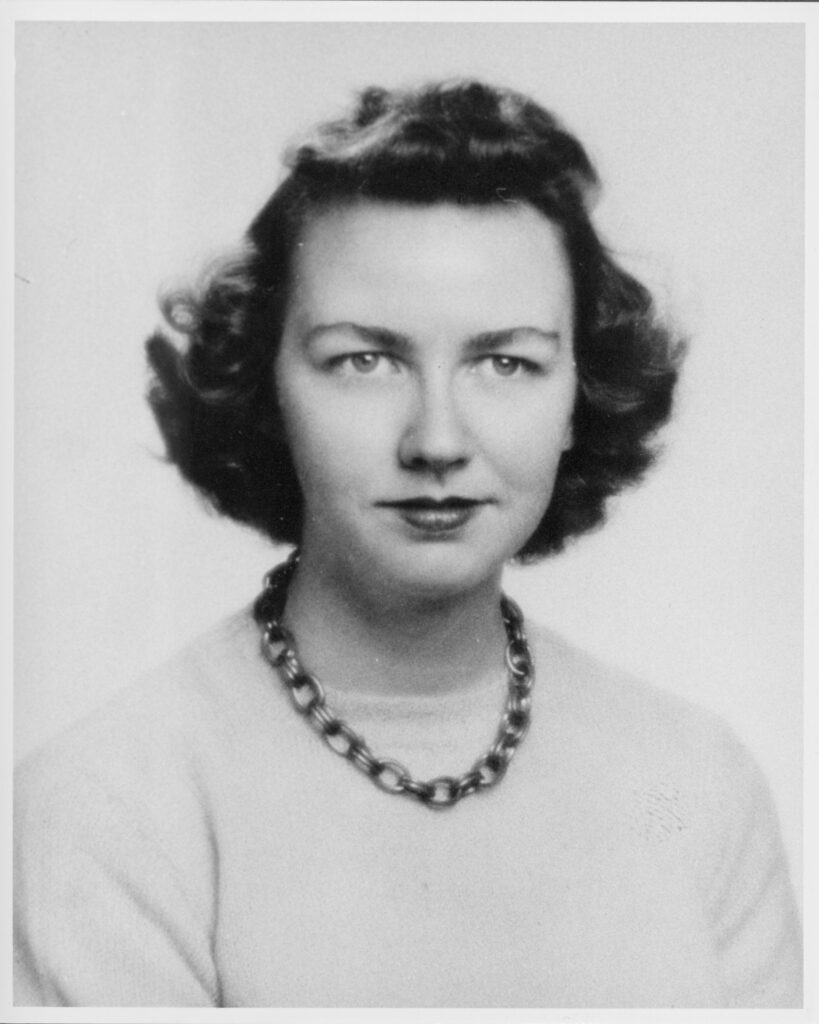

Courtesy of Ina Dillard Russell Library, Georgia College and State University

In 1972 the posthumous collection The Complete Stories received the National Book Award, usually given to a living writer. The judges deemed O’Connor’s work so deserving that an exception was made to honor her lifetime achievement. In 1979 The Habit of Being: Letters, edited by Sally Fitzgerald, was published to rave reviews. These letters reveal a great deal about O’Connor’s life in Milledgeville, her writing habits, and most important, her profound religious convictions. For the first time readers were able to see—beyond the shocking stories—the warm and witty personality and the incisive intellect of the writer. The collection of letters received a number of awards, and Christian Century magazine named The Habit of Being one of the twelve most influential religious books of the decade.

Works and Common Themes

O’Connor’sfirst novel, Wise Blood, received mixed reviews. Even some of the strongest commentators on southern literature seemed to be at a loss to describe this dark novel. While working on the novel in the early years, O’Connor had defied an insistent and authoritative editor at Rinehart by stating that Wise Blood was not “a conventional novel,” so confident was she in her intent. Scholars who have spent time in the O’Connor Collection in the Georgia College and State University library know that even O’Connor’s juvenilia anticipate the relentlessly stark vision that became the mature writer’s trademark. The closest literary “kin” of Wise Blood in American letters arguably is Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts; both novels are filled with black humor and written in a sharply honed style. A novel of spiritual quest, Wise Blood presents the male “pilgrim,” Hazel Motes, as inhabiting a sterile and ugly modern landscape derivative of T. S. Eliot’s Waste Land.

Courtesy of Ina Dillard Russell Library, Georgia College and State University

The publication of her first short-story collection, A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955), made O’Connor’s Christian vision and darkly comic intent somewhat clearer to readers and allowed them to more easily grasp the intent of her 1960 novel, The Violent Bear It Away. A second collection of stories, Everything That Rises Must Converge, published posthumously in 1965, contains some of O’Connor’s most popular short fiction, including the title story and “Revelation.”

The body of O’Connor’s work resists conventional description. Although many of her narratives begin in the familiar quotidian world—on a family vacation or in a doctor’s waiting room, for example—they are not, finally, realistic and certainly not in the sense of the southern realism of William Faulkner or Erskine Caldwell. Furthermore, although O’Connor’s work was written during a time of great social change in the South, those changes—and the relationships among Blacks and whites—were not at the center of her fiction. O’Connor made frequent use of violence and shock tactics. She argued that she wrote for an audience who, for all its Sunday piety, did not share her belief in the fall of humanity and its need for redemption. “To the hard of hearing,” she explained, “[Christian writers] shout, and for the… almost-blind [they] draw large and startling figures”—a statement that has become a succinct and popular explanation of O’Connor’s conscious intent as a writer.

O’Connor had read Faulkner and Caldwell, as well as Eudora Welty, Caroline Gordon, and Katherine Anne Porter, among southern writers. Faulkner and Porter were strong influences, as were Nathaniel Hawthorne, Joseph Conrad, and the French writers Georges Bernanos and François Mauriac. These last four reinforced O’Connor’s emphasis on original sin, guilt, and alienation, especially as she focused on the twentieth-century tendency to find in technology and in the idea of “progress” the panacea to life’s ills. Although O’Connor knew that she—like her early model T. S. Eliot—was in the minority in her disdain for the increasing secularism of her time, she refused to back down.

Courtesy of Ina Dillard Russell Library, Georgia College and State University

Flannery O’Connor was a painstaking and disciplined writer, devoting each morning to her work and making great demands of herself even in her last years as she struggled with lupus. She possessed a keen ear for southern dialect and a fine sense of irony and comic timing; with the combination of these skills, she produced some of the finest comedy in American literature. Like the comedy of Dante, O’Connor’s dark humor consciously intends to underscore boldly our common human sinfulness and need for divine grace. Even her characters’ names (Tom T. Shiflet, Mary Grace, Joy/Hulga Hopewell, Mrs. Cope) are often ironic clues to their spiritual deficiencies. O’Connor’s recurrent characters, from Hazel Motes in Wise Blood to O. E. Parker of “Parker’s Back,” are spiritually lean and hungry figures who reject mere lip service to Christianity and the bland certainty of rationalism in their pursuit of salvation. These same characters, usually deprived economically, emotionally, or both, inhabit a world in which, in O’Connor’s words, “the good is under construction.”

O’Connor was a Roman Catholic in the Bible Belt South; her fiction, though, is largely concerned with fundamentalist Protestants, many of whom she admired for the integrity of their search for Truth. The publication of her essays and lectures, Mystery and Manners (1969), and the publication ten years later of The Habit of Being confirmed the strong connection between O’Connor’s fictional treatment of the search for God and the quest for the holy in her own life. Indeed, her life and work were of a piece. She attained in her brief life what Sally Fitzgerald called (after St. Thomas Aquinas) “the habit of being,” which Fitzgerald describes as “an excellence not only of action but of interior disposition and activity” that struggled to reflect the goodness and love of God.

In 1992 O’Connor was inducted as an inaugural honoree into Georgia Women of Achievement, and in 2000 she was inducted as a charter member into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.