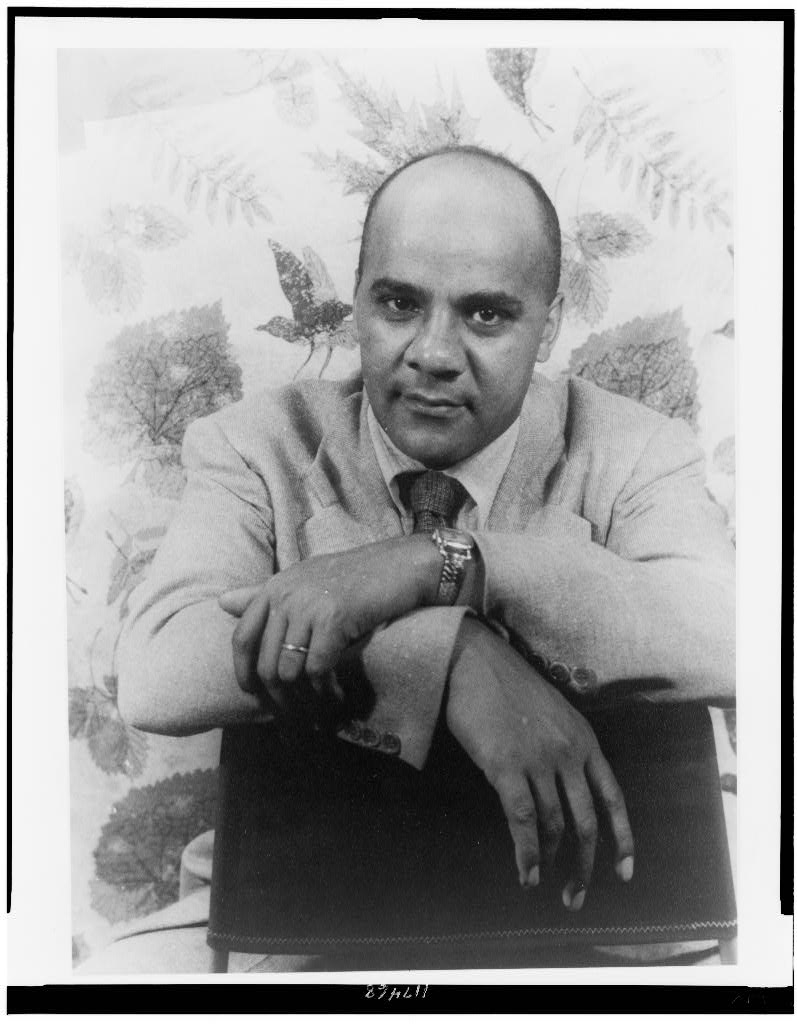

Writer John Oliver Killens, a native of Macon, drew on his own encounters with racism to compose such works as Youngblood, a classic of social protest fiction.

Working within a tradition that coupled art with activism, Killens said, ”There is no such thing as art for art’s sake. All art is propaganda, although there is much propaganda that is not art.” The founding chairman of the celebrated Harlem Writers Guild, Killens became a spiritual father of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s. Like the writer Richard Wright, whom he greatly admired, Killens inspired a subsequent generation of African Americans through writings charged with strong social and political messages.

Killens was born on January 14, 1916, to Charles Myles Killens Sr., a restaurant manager, and Willie Lee Coleman, an insurance company clerk. His parents were well-read and kept abreast of trends and events important to African Americans. Along with Killens’s great-grandmother, his parents instilled in him a pride in Black culture and a belief in the power of the arts to effect social change.

Education and Military Service

Killens graduated in 1933 from Ballard Normal School in Macon, a private institution run by the American Missionary Association and, at the time, one of the few secondary schools for Blacks in Georgia. With the aim of becoming a lawyer, Killens did his undergraduate course work at Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida; Morris Brown College in Atlanta; and Howard University in Washington, D.C. He then attended the Robert H.Terrell Law School in Washington, D.C., but quit before his final year to study creative writing at Columbia University in New York.

His college years encompassed other formative experiences: a stint at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), military service, and marriage. His work with the NLRB turned him into a lifetime advocate for organized labor. During World War II (1941-45) Killens served from 1942 to 1945 in a U.S. Army amphibious unit. He spent more than two years in the South Pacific and rose to the rank of master sergeant. In 1943 Killens married Grace Ward Jones, with whom he had two children: a son, John Charles, and a daughter, Barbara.

Writing Career

In the early 1950s Killens, who had settled in New York, joined three of his friends to form the Harlem Writers Guild. Killens polished his first novel, Youngblood (1954), at meetings in members’ homes. Spanning the Jim Crow era through the Great Depression, it portrays ordinary Black people in the fictional rural community of Crossroads, Georgia, as they struggle to maintain their dignity and secure their rights.

His second novel, And Then We Heard the Thunder (1963), is about a law school student who, just as Killens did, interrupts his education to serve in an all-Black amphibious regiment in World War II. As an officer, the main character endures not only the hardships of war but also the bigotry of his white fellow officers. Critic Jonathan Yardley of the Washington Post wrote that it was “one of the few distinguished novels about World War II” and a “powerful—though regrettably little-known—examination of the lives of Black servicemen.” Another of Killens’s important works is the novel The Cotillion; or, One Good Bull Is Half the Herd (1971). Satirizing class pretensions, The Cotillion uproariously portrays the conflicts between militants and social climbers within Black society in the 1960s.

Killens published six novels in his lifetime. Additional book-length works include Black Man’s Burden (1965), essays on race in America; Great Black Russian (1989), a posthumously published novel on the poet Alexander Pushkin; and two books for young readers, Great Gittin’ Up Morning (1972), a biography of Denmark Vesey, and A Man Ain’t Nothin’ but a Man (1975), which recounts the adventures of John Henry. Killens also wrote plays, screenplays, and numerous articles and short stories that appeared in publications ranging from Black Scholar and the New York Times to Ebony and Redbook. His works have been published in some fifteen countries, and a representative sampling remains in print today.

Activism and Honors

When Killens was not writing, he worked for social causes and racial equality. A man whose low-key manner belied his hard-edged activist beliefs, Killens knew both Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X—but identified more closely with the latter. Killens once wrote, ”My fight is not to be a white man in a Black skin, but to inject some Blackblood, some Black intelligence into the pallid mainstream of American life.” As a writer-in-residence at Howard University; Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee; and Medgar Evers College in New York, Killens was known as a generous, encouraging mentor. He was instrumental in establishing Black writers’ conferences at each of the schools.

Killens’s many honors include the vice presidency of the Black Academy of Arts and Letters, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship (1980), and a Distinguished Writer Award from the Middle Atlantic Writers Association (1984). The Before Columbus Foundation, which sponsors the American Book Awards, cited Killens for lifetime achievement in 1985. He is also a member of the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.

Killens died on October 27, 1987. His novel The Minister Primarily (2021), a satirical exploration of race in America, was discovered and published more than three decades after his death.