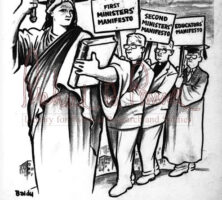

In November 1957, after witnessing the school integration crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas, eighty members of the Atlanta Christian Council issued a statement of conscience discouraging city officials and ordinary citizens from pursuing a course of massive resistance to federal authority. Better known as the “Ministers’ Manifesto,” the statement called for moderation, communication between the races, racial amity, and most importantly, obedience to the law. One year later, after the Temple bombing in Atlanta aroused new fears of racial extremism, more than 300 ministers issued a second manifesto calling for the creation of a citizens’ commission to debate alternatives to massive resistance. Both statements helped defuse the city’s racial tensions, and helped earn Atlanta a reputation as “the City Too Busy to Hate.”

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Background

When the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, which called for the desegregation of public schools, southern legislators responded by adopting a program of massive resistance to federal authority. In state legislatures throughout the South, conservative lawmakers passed a variety of measures designed to prevent or indefinitely delay the integration of public schools. In Georgia, a year prior to the Brown decision, lawmakers approved a constitutional amendment authorizing the General Assembly to privatize the state’s public school system in the event of court-ordered desegregation. In 1956 the General Assembly went a step further, amending the state constitution to enable public school teachers to retain retirement benefits at private institutions, and making arrangements to transfer all public school property to private hands.

At the federal level, the majority of southern congressmen and senators, including the entire Georgia delegation, indicated their opposition to Brown by signing the “Declaration of Constitutional Principles” of 1956. Called the “Southern Manifesto,” the declaration condemned the court’s decision as a “clear abuse of judicial power” and announced the signers’ intention to “resist forced integration by any lawful means.” When coupled with measures already taken by lawmakers at the state level, the manifesto was, according to one legal scholar, “a calculated decision of political war.”

Tensions came to a head in September 1957, when a federal court order forced the Little Rock Board of Education to admit a small number of Black students to Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. At the behest of Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard assembled outside the school and, with the help of an angry white mob, blocked the students’ entry. Although U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower later resolved the matter by dispatching federal troops to restore order and force the school’s integration, the Little Rock crisis was an unfortunate ordeal, and many observers correctly speculated that the city’s economy and reputation would suffer as a result.

Ministers’ Manifesto

In order to prevent a similar scenario from occurring in Atlanta, eighty white members of the Atlanta Christian Council issued a statement that appeared in both the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution on November 3, 1957. The ministers identified six tenets to observe during the city’s integration debates: freedom of speech, obedience to the law, preservation of public schools, mutual respect and goodwill, interracial communication, and the guidance of prayer. In a carefully worded disclaimer, the signatories explained that they spoke only for themselves, and they assured readers that their prescriptions were proffered “in a spirit of deep humility and of penitence for our own failures.” Their statement was nevertheless necessary, they concluded, because “men who occupy places of responsibility in the churches should not be silent concerning their convictions.”

The Ministers’ Manifesto, as it came to be known, was the first document of its kind: a clear, if cautious, challenge to the rhetoric of massive resistance by an established southern moral authority. Although it lifted the veil of silence that had previously prevented Atlanta’s racial moderates from debating alternatives to massive resistance, the manifesto’s influence appeared to wane in the months after its initial publication. Concerns over the Little Rock crisis subsided in Atlanta until the next year, when the 1958 Temple bombing renewed fears of extremism in the city.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Although he did not sign the manifesto due to its strong Christological rhetoric, Jacob Rothschild, the Temple’s rabbi, helped draft the statement and endorsed it in an editorial published separately in the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution. Rothschild remained steadfast and vocal in his defense of racial moderation following the manifesto’s publication, unfortunately making the Temple a likely target of extremist violence.

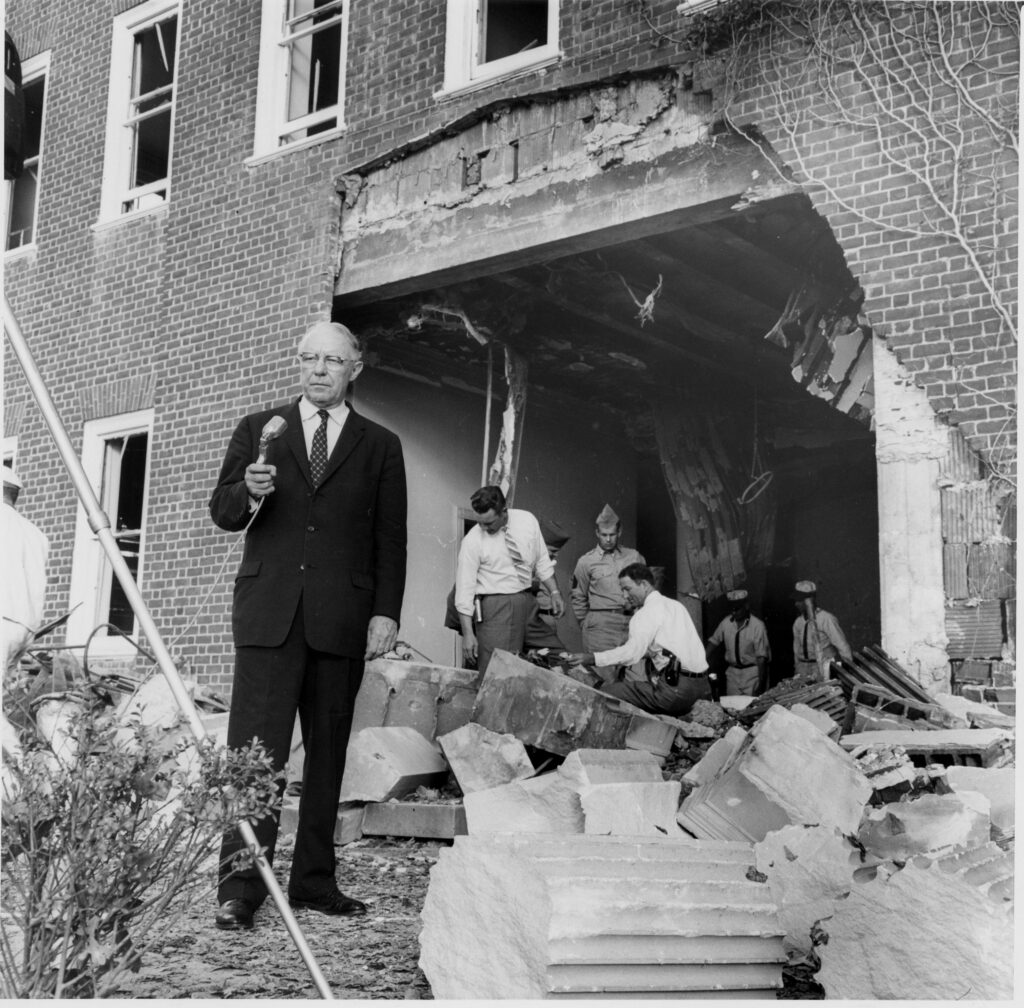

In the wake of the bombing on October 12, 1958, city officials and members of the press denounced massive resistance as a foolhardy and irresponsible solution to the region’s racial woes. “Whether they like it or not,” stated Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield, “every political rabble-rouser is the godfather of these cross burners and dynamiters.” He also condemned those “who sneak about in the dark and give a bad name to the South. It is high time the decent people of the South rise and take charge.” Local clergymen answered the mayor’s challenge by issuing a second Ministers’ Manifesto, “’Out of Conviction’: A Second Statement on the South’s Racial Crisis,” in early November 1958, just three weeks after the Temple bombing. The pamphlet called for an open discussion of the city’s impending integration crisis and encouraged the governor to appoint a citizens’ commission to hold hearings on the matter throughout the state. Whereas only 80 ministers dared to sign the first manifesto, more than 300 signed the second.

Integration

In February 1960, after a federal court ordered the city of Atlanta to desegregate its schools, Georgia governor Ernest Vandiver established the General Assembly Committee on Schools to determine public opinion on integration throughout the state. Referred to as the Sibley Commission, after its chairman, John Sibley, the group traveled to every congressional district in the state, holding hearings and assessing public sentiment.

Officially, state officials were still committed to closing schools in the event of a desegregation order, but Atlanta’s political leadership proposed a “local option” alternative that would allow local communities the option of closing schools or accepting token integration. Although the Sibley Commission’s hearings reflected strong support for “open schools” in Atlanta, statewide public opinion favored closing Georgia’s schools, if only by a small margin. Popular opinion notwithstanding, however, the commission’s Majority Report endorsed the local option as a desirable alternative to the abolition of Georgia’s public education. Following the publication of the Sibley Commission’s findings, the General Assembly passed a local option bill that included a clarified pupil-placement process designed to limit the scope of integration.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

A host of journalists descended on Atlanta in August 1961 to witness the desegregation of the city’s public schools. As the nation watched, Mayor Hartsfield presided over a peaceful desegregation process. Despite the relatively modest scope of the city’s integration policy—only nine Black students integrated formerly all-white city schools—Atlanta received high marks from the national media. U.S. president John F. Kennedy recognized Atlanta’s effort in a press conference, and the national publications Good Housekeeping, Life, Look, Newsweek, and the New York Times ran stories applauding the city’s moderate racial climate.