The Spanish chapter of Georgia’s earliest colonial history is dominated by the lengthy mission era, extending from 1568 through 1684. Catholic missions were the primary means by which Georgia’s indigenous Native American chiefdoms were assimilated into the Spanish colonial system along the northern frontier of greater Spanish Florida.

Establishment of Missions

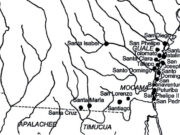

Following the largely unsuccessful conversion efforts of Jesuit priests between 1568 and 1570, friars of the Franciscan Order spearheaded the establishment of missions among Indian groups near Florida’s Spanish colonial city, St. Augustine. After a brief effort among the coastal Guale in 1574-75, the Franciscan mission era shifted into full gear after the 1587 arrival of a group of friars from Spain. The first successful mission established in Georgia was San Pedro de Mocama, founded in the capital town of the Timucua-speaking Mocama chiefdom on the southern end of present-day Cumberland Island. By the end of 1595 missions had also been established in at least one other Mocama town and no fewer than five main towns of the Muskogee-speaking Guale chiefdom on the northern Georgia coast. One of these missions, the Santa Catalina de Guale on St. Catherines Island, later became the capital. When five friars were murdered in the Guale rebellion of 1597, northern missions were abandoned completely until 1604. Nonetheless, additional missions were established in other coastal locations and in the state’s Timucuan interior during the first quarter of the seventeenth century. They extended from the forks of the Altamaha River across the Okefenokee Swamp to the upper watersheds of the Alapaha and Withlacoochee rivers.

Spanish missions were explicitly established for the purpose of religious conversion and instruction in the Catholic faith. However, the mission system actually served as the primary means of integrating Indians into the political and economic structure of Florida’s colonial system. Missions were normally established at the political center of local chiefdoms, in the villages where the chiefs lived and where the council houses were located. Each mission was only a small compound within a much larger Indian community. The mission typically included a church structure (where Mass was celebrated and where Indian converts were buried) and a convent, or friary, where a single friar lived alone. Because chiefdoms were made up of a number of outlying satellite villages and hamlets, friars normally served a much larger group of Indians within their visitation rounds. Some subordinate communities had uninhabited secondary church structures as well.

Friars and Chiefs

Although Franciscan friars were clearly in charge of religious affairs, they were politically subordinate to governing Indian chiefs, whose authority in secular matters was rarely contested. Chiefs ruled with the assistance of hereditary counselors (their noble male relatives) and subordinate village headmen, and decision making was carried out in the council house. All direct interaction with Spanish military authorities in St. Augustine was through the mediation of these hereditary chiefs. Nevertheless, the resident friars, who acted as subordinate religious practitioners on a day-to-day level, frequently acted as agents for the chiefs in disputes with the Spanish governor or military officers. The chiefs normally maintained considerable autonomy over their own local societies. They gained prestige and legitimacy in the eyes of their subordinates through acquiring ornate Spanish clothing and other trade goods. Even though they were subordinate to the Spanish crown and church, Indian leaders found considerable benefits in becoming part of the mission system. Consequently, it was normally the chiefs who requested the dispatch of friars and the construction of missions, and not the other way around.

Effects of the Mission System

One important consequence of allegiance to the Spanish crown and incorporation into the Florida mission system was the repartimiento. Under this system of obligatory wage labor a specified number of unmarried male Indians were required to go to St. Augustine each year to work in the Spanish cornfields or to build and maintain Spanish fortifications. Chiefs could select which subordinates were drafted each year, and these workers were paid in inexpensive trade goods for each day of labor. Up to 300 mission Indians from across Spanish Florida were drafted annually for work between March and September, causing considerable change in the native societies. Workers often caught and spread epidemic diseases during their terms of service, and sometimes they died as an indirect result of overwork and exhaustion.

The absence of available male marriage partners also led to a demographic imbalance in the mission villages, especially when some workers chose or were forced to remain permanently in St. Augustine. Ultimately, however, the chiefs and village headmen voiced few complaints, as long as the workers acted as dutiful intermediaries in this labor arrangement.

Decline of Missions

Over the course of the mission period Indian population levels declined rapidly and substantially, plummeting well over 90 percent in many areas. Depopulation, combined with widespread forced resettlements dating to 1656 and 1657, eventually led to the abandonment of Georgia’s interior missions. Beginning with a devastating 1661 raid on the Santo Domingo de Talaje Mission at the mouth of the Altamaha River, there were also armed slave-raids by Indians allied with the English. These raids finally resulted in the retreat of all coastal missions to the barrier islands by 1685.

During this same period, refugees who came to be known as Yamasee Indians also settled briefly among the Mocama and Guale. They fled during pirate raids against the missions in 1683 but later joined the English in slave-raids on Florida. A final pirate raid in October 1684 left Georgia’s remaining missions in ruins, ending the mission period in this state. Georgia’s surviving mission Indians retreated south of the St. Marys River, where they were pushed farther southward. All remaining missions across Spanish Florida had retreated to St. Augustine by the summer of 1706. The surviving descendants of Georgia’s Guale and Mocama missions were among the eighty-nine Indians who chose to evacuate Florida with the Spanish in 1763, relocating permanently to Cuba.