In hindsight, the controversy that greeted the publication of Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit in 1944 seems unusually heated today. This novel of interracial love was denounced in many places for its “obscenity,” although sex is barely mentioned. Massachusetts banned it for a short time; so did the U.S. Post Office. But the book has had many admirers in the years since its publication. It was a commercial success—a best-seller, a Broadway play briefly—and it remains in print in many languages. From her home atop Old Screamer Mountain near Clayton, in Rabun County, Smith knew that many of her neighbors had bought the book, but in public they snubbed her.

In 1949 she unleashed another diatribe against racism in an imaginative autobiography, Killers of the Dream, widely considered to be her best book. In Strange Fruit and subsequent writings, Smith attempted to untangle and expose the web of white racism, gender, class, religion, and myriad traditions she thought had put a straitjacket on what her contemporary and admirer, W. J. Cash, called “the mind of the South.” She was the first white southerner of any prominence to denounce not just racism but segregation.

Strange Fruit is set in the imaginary small south Georgia town of Maxwell, modeled obviously on the town of Jasper, Florida, Smith’s birthplace and home for her first seventeen years. The novel’s central events, set against a week of religious revival in August, occur immediately after World War I (1917-18). Tracy Deen, son of middle-class but pretentious white parents, has just returned from a stint in the army. He and Nonnie Anderson, a younger, pretty, light-skinned African American who has been in love with him since she was a very young girl, immediately find themselves in each other’s arms. When Nonnie learns that she is pregnant, she allows herself to hope that Tracy will be as happy as she is. He isn’t. He has been mired in guilt and self-doubt, and her news only heightens his uncertainty about religion and about his mother’s constant urgings that he join the church and marry his presumed sweetheart, a pleasant, conventional young girl. The dreamy Tracy tries to buy Nonnie off with money for an abortion—available in nearby Atlanta to white girls—or a marriage to any Black man.

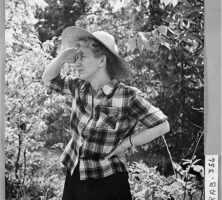

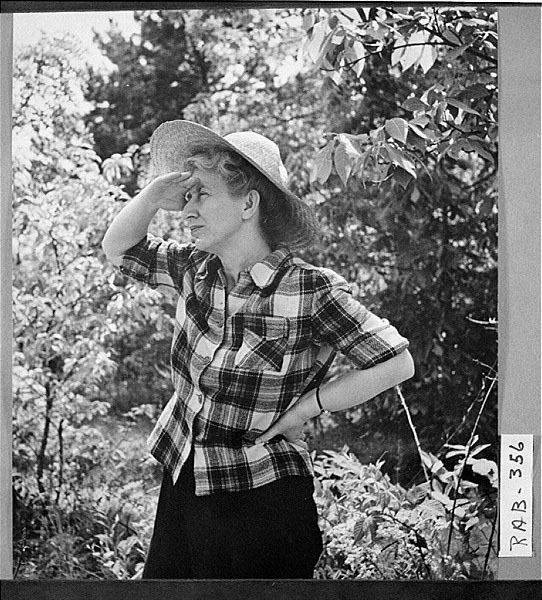

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Every southern social force—racism, religious fundamentalism, class conflict—is at war in the dilemma and dreams of the two protagonists, and the consequence is nothing but tragedy for everyone, even Tracy’s innocent, simpleminded Black boyhood friend. Lillian Smith was earnest and idealistic, more a social critic than a novelist. She never missed a chance to denounce the corrosiveness of traditions, whether expressed by a dimwitted racist, such as Preacher Dunwoodie, or by Nonnie’s angry older brother, who resorts to murder and brings on unintended tragedy.

Smith always believed her novel had been deliberately underrated and misunderstood. She deeply resented criticism from prominent white moderates such as Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill. She was hurt when Black intellectuals complained that she had patronized Nonnie by portraying the intelligent, college-educated young woman as in a perpetual swoon for a marshmallowy lover who could hardly have treated her more shabbily.

Smith’s attitude toward the novel also seemed to change over time. In 1961 she rebuked a literary agent who was trying to negotiate a film version. No one admitted that her novel was a masterpiece, Smith said; people erroneously still viewed the book as being simply about race relations. She even suggested that a white actress could play Nonnie’s role. She said her novel was not about race (which it surely was) but instead was a fantasy in which she was every character. Whatever else it might be, Strange Fruit is about relationships, crossing lines, breaking rules, being different, rejecting prescribed rules, transcending categories, and those “racial abstractions” that Smith often said existed only to divide and conquer and corrupt their victims.