The tenth president and the first chancellor of Emory University, Southern Methodist Episcopal bishop Warren Akin Candler was the tenth of eleven children born to Samuel Candler, a prosperous Villa Rica merchant and planter, and his wife, Martha Bernetta Beall. Reared in a devout atmosphere, Candler attended Emory College in Oxford, Georgia, from 1874 to 1877. There he discovered his religious vocation and a considerable talent for preaching that would make the Southern Methodist Church the center of his life. After he left Emory he soon married Sarah Antoinette “Nettie” Curtright. The couple had five children, three of whom lived to adulthood.

As a young minister, Candler served several churches in northwest Georgia. In 1882, along with George Foster Pierce, bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Lucius Holsey, bishop of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (later Christian Methodist Episcopal Church), and others, Candler helped found Paine Institute (later Paine College) in Augusta. Paine’s mission was the higher education of African American leaders. As a longtime member of Paine’s board of trustees, Candler supported the hiring of African Americans to teach, thus creating a racially integrated faculty for the school.

From 1886 to 1888, as assistant editor of the Nashville, Tennessee, Christian Advocate, he supported some of the goals of the evangelical Holiness Association, although he feared that the association might also be divisive.

In his next assignment, as president of Emory College (where students nicknamed him “Shorty”), Candler advanced firmly conservative views. In the decade from 1888 to 1898 he phased out technological training and implemented a liberal arts curriculum. He also improved the school’s finances and increased the size of the faculty. Made a bishop in 1898, he then concerned himself with such denominational affairs as missionary enterprises.

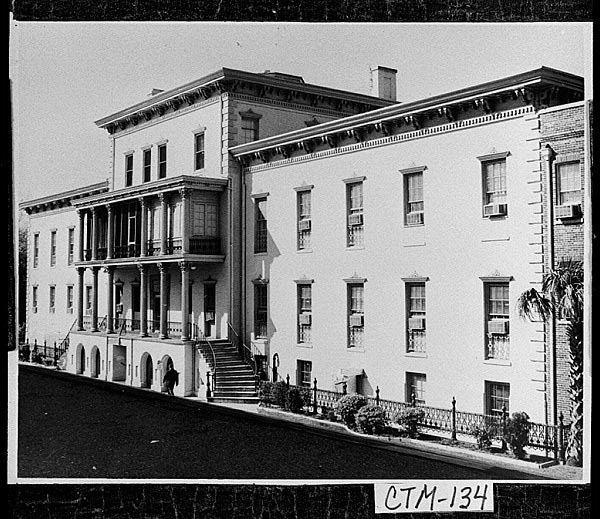

As spiritual advisor to his brother Asa Candler, founder of the Coca-Cola Company, he encouraged Asa’s support of church causes. The most notable of these was the creation of the Emory University campus in Atlanta. This came about when Bishop Candler and some of his fellow churchmen, who served on the board of trustees of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, lost influence over that institution. After an unsuccessful 1910 lawsuit to regain their authority, the Southern Methodists decided to establish two new educational institutions, which would be under their control. The first was Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; the second was to be located somewhere east of the Mississippi River. The Candler brothers combined their influence and resources to win this role for Emory College. Asa Candler wrote a check for $1 million to defray expenses of moving Emory’s headquarters from Oxford to acreage he donated in his Druid Hills development in the eastern suburbs of Atlanta.

After becoming the first chancellor of Emory University, in 1914, Bishop Candler fought for traditional values, forbidding such activities as dramatics clubs and intercollegiate athletics. In addition to the Candler School of Theology, Emory established law and medical schools and opened a university hospital, but Candler’s hope of establishing a school of education never came to fruition. He expended great effort in raising funds for the institution. In 1918 he expressed his desire to retire as chancellor but did not step down until 1922. He remained active as a trustee until 1937.

For three decades Candler wrote a column in the Atlanta Journal. He also wrote many articles for religious publications and fifteen books on biographical and religious topics. His thinking represented traditionalism tempered by religious idealism. Although he wrote of his belief in Anglo-Saxon superiority, Candler spoke out strongly against lynching. He was not a critic of the American economic system, but he opposed the power of trusts and condemned covetousness in general. A supporter of the traditional Christian creed, he also sought to mitigate the conflicts of science and religion.

Bishop Candler opposed the reunification of the Northern and Southern Methodist churches, which had split before the Civil War (1861-65) over the issue of slavery. Proponents of reunification persuaded the General Conference of the church to establish a rule requiring the retirement of bishops who had reached seventy-two years of age. This rule removed Candler and another opponent of reunification from the conference in 1934. Candler continued to write and announced his intention to “preach until I die.” He received many honors and gestures of public affection, including the gift of a Franklin sedan. He died on September 25, 1941, and is buried in a cemetery adjacent to the Emory campus. Nettie, his wife of more than sixty years, died two years later.