The term Federal Road refers to either of two early-nineteenth-century thoroughfares. Both connected the borders of Georgia with western settlements. These roads facilitated a surge of westward migration, expanded regional trade and communication, and contributed to the removal of the Creeks and Cherokees to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

The roads were one instance of the federal government’s agenda of “internal improvements,” government-subsidized projects that would tie together the trade and people of the young nation. With the goal of joining settlements in Tennessee and Alabama more closely with those in Georgia, the government negotiated a series of fraudulent treaties with the Creek and Cherokee Indians. In 1805, through the Treaty of Tellico with the Cherokees and the Treaty of Washington with the Creeks, the government gained the right to open and operate roads through Indian lands.

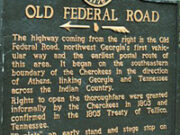

The surveying and constructing of the road through Cherokee lands began around 1810. The name notwithstanding, the federal government took little role in building this road, leaving it instead to the governments of Georgia and Tennessee, and to Cherokee entrepreneurs. Much of the route followed an old Cherokee trading path. The road connected Georgia with Nashville and Knoxville, both frontier settlements in Tennessee. From Athens the route led northwestward along a generally straight course, entering the lands of the Cherokees at the present Hall County–Jackson County line and heading toward what is now Ramhurst in Murray County. There it forked, one branch leading north to Knoxville and the other west to Ross Landing, now Chattanooga. Portions of modern roads traverse the route of the Federal Road, and in some places road signs indicate “Old Federal Road.” State historical markers in Catoosa, Hall, Forsyth, Murray, Pickens, Walker, and Whitfield counties also indicate the route.

The federal government played a more direct role in the building of the road through Creek lands. In 1806 the Postal Department oversaw the clearing of a horse path running from Athens to Fort Stoddert, north of Mobile, Alabama, and then on to New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1811 the U.S. Army rerouted and widened this path, adhering closely to the route of the old Lower Creek trading path. It began at Fort Wilkinson near Milledgeville, then the state capital, and headed southwest. At present-day Macon it entered the lands of the Lower Creeks,heading on toward the Chattahoochee River about nine miles south of Columbus. As with the road through the Cherokee lands, some modern roads follow portions of the old road. State historical markers in Chattahoochee, Marion, and Taylor counties show the route.

Mail carriers, western settlers and enslaved African Americans, evangelical itinerants, the military in the War of 1812 (1812-15) and the Seminole War, and European travelers in stagecoaches used the roads. The hordes of pioneers who traveled west on these roads wanted new land and a chance at upward mobility, and their desires hastened the federal government’s scheme of removing the Indian population to lands beyond the Mississippi River. By armed force and manipulation, the government in the 1830s expelled the Creeks and Cherokees from the lands the Federal Road passed through. Soon after, however, the road ceased to be a mechanism for change, as railroads were laid out in the 1830s and 1840s, taking over many of the functions that the roads had once served.