The Flint River Farms Resettlement Community in Macon County, named for the Flint River, which flows nearby, was one of several experimental planned communities established in 1937, during the Great Depression, under U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The community became home to 106 African American families, most of whom had previously lived on the surrounding plantations, where they worked as sharecroppers.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In an effort to elevate sharecroppers and tenant farmers into landowners and to alleviate poverty in rural areas, the federal government implemented a number of farm-ownership programs, which were brought together in 1935 under the newly formed Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration. The Resettlement Administration purchased more than 1.8 million acres of land in almost 200 locales across the country and established a series of supervised farming and industrial communities. Thirteen of these resettlement communities, encompassing 1,150 families on 92,000 acres of land, were designated for African American farmers in the South, and one—Flint River Farms—was located in Georgia.

The evolution of Flint River Farms began in Fort Valley (in Peach County) in 1935 with a request to the Division of Rural Resettlement in Washington, D.C., for a 6,000-acre resettlement project in the county. In June 1936 Fort Valley Farms was authorized and approved. The plans for the project included not only 150 farms but also a community building that would serve as a school and health center.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Soon after the plans for the Fort Valley Farms project were approved, however, opposition from white residents came in the form of petitions to reject the project, which were addressed to local and national politicians and circulated throughout Peach County. In reaction to this opposition, approval was given for the Fort Valley Farms project to be moved near the adjacent town of Montezuma, in Macon County, in November 1936. Before plans could be finalized for Macon County, however, a few highly vocal citizens expressed their opposition to the development through letters and petitions. In one case, approximately 450 citizens signed a petition, although many did so after being given misinformation. Nevertheless, the project received support from the Montezuma City Council as well as the local Kiwanis Club. The project went forward, and Fort Valley Farms officially became Flint River Farms in May 1937.

Farm Design and Administration

Flint River Farms began on approximately 11,000 acres of land, comprising 11 tracts from several large plantations purchased by the federal government. The land was subdivided into 107 farm units averaging 93 acres per unit. Two units were eventually combined, resulting in 106 units available for settlers. Each unit consisted of a new four- or five-room house, a barn, two mules, an outhouse, a chicken coop, and a smokehouse, along with bored wells, sanitary privies, and fencing. The Rural Electrification Administration installed electrical lines to each unit. The houses and farm buildings were constructed of wood on all but two of the units, where the buildings were constructed entirely of special rust-resistant steel, except for the doors and floors.

The resettlement families were required to sign lease-purchase agreements. After a five-year trial period, successful farmers were offered forty-year mortgages at 3 percent interest to purchase the land. In 1943 the U.S. government first sold some of the farms to private owners, and by year’s end almost half the units were sold. By 1945 nearly 90 percent of the units were sold, and the sales of the last two farm units occurred in 1948.

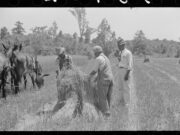

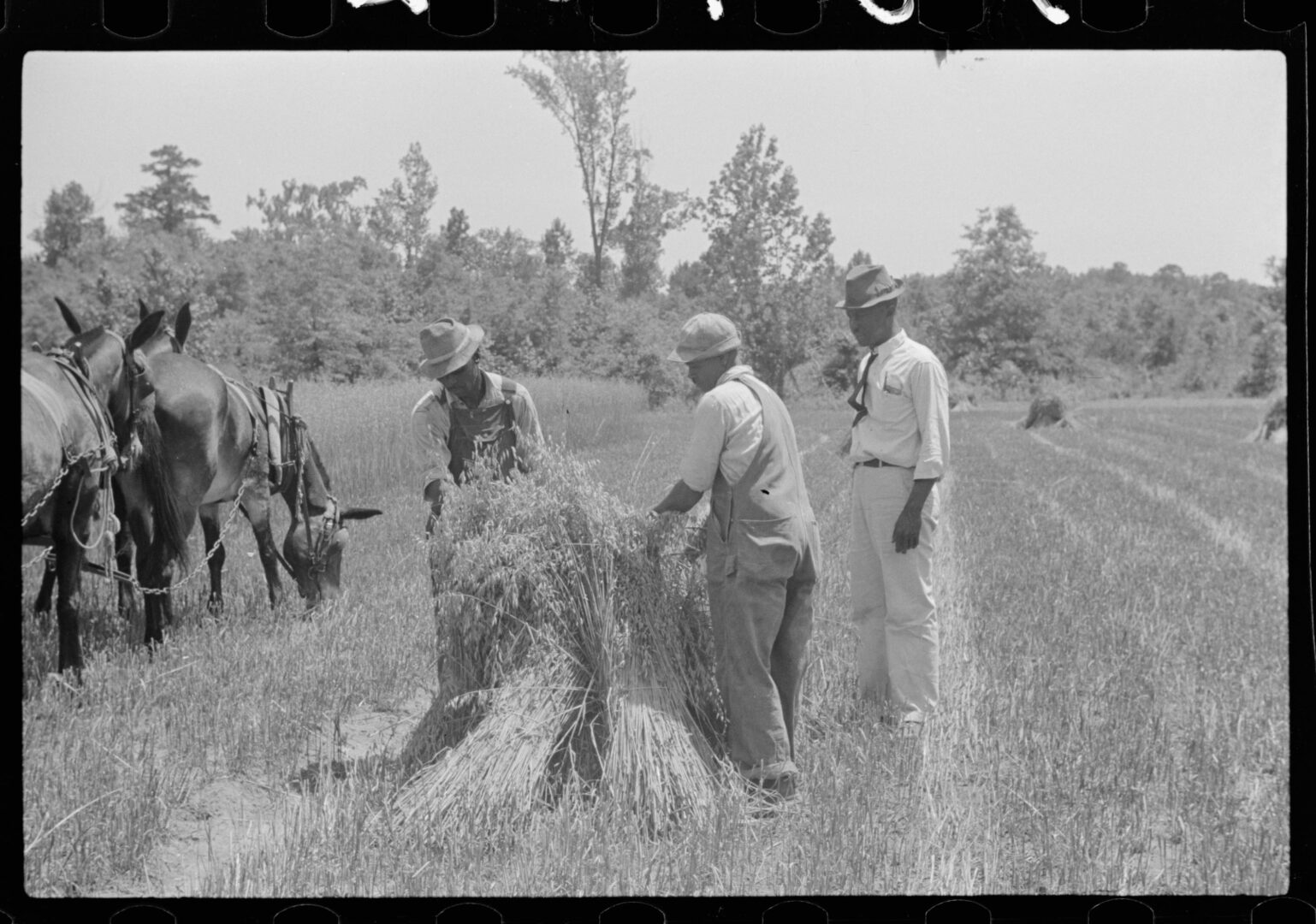

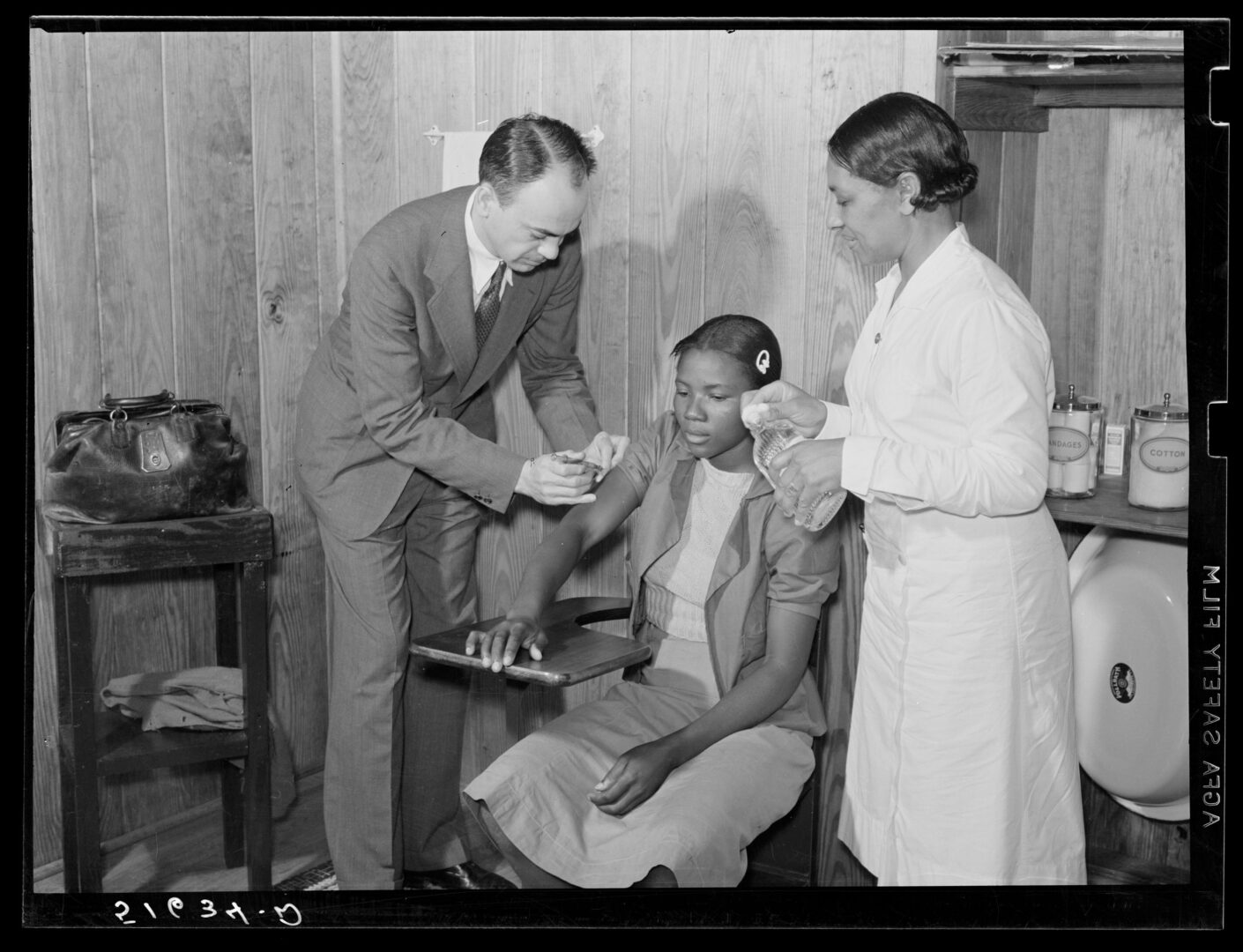

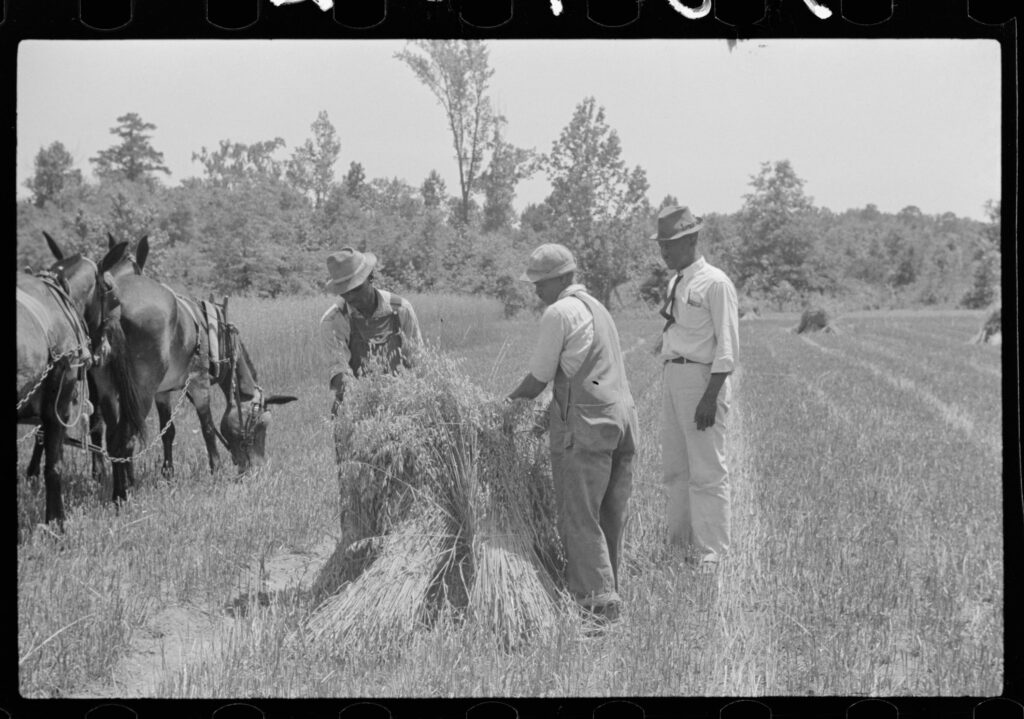

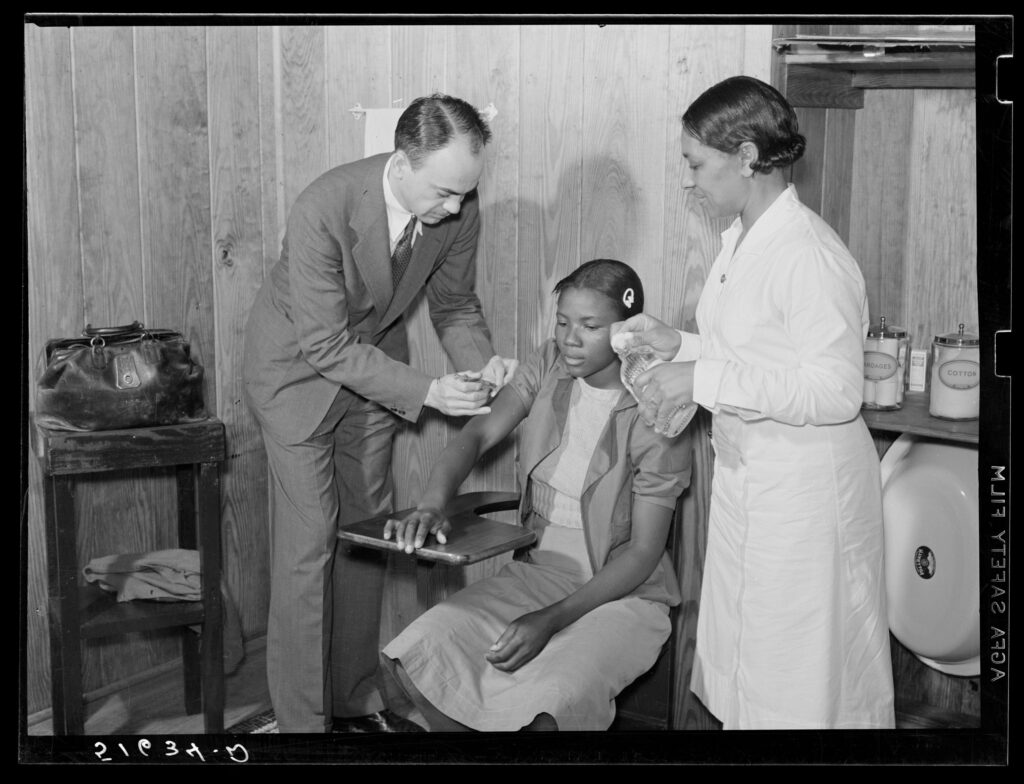

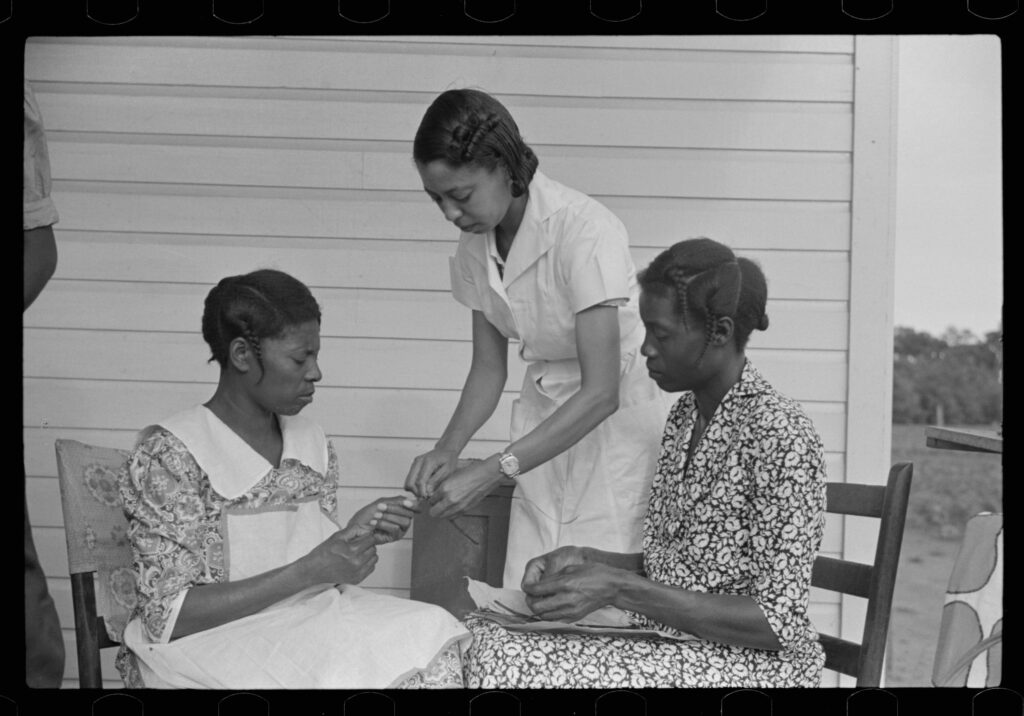

Key to the success of Flint River Farms was the establishment of a four-member project staff, which focused on farm and household activities for men and women, as well as overall family health. This staff included project manager Amos Ward, farm supervisor Alonzo Fields, home management supervisor Evelyn N. Driver, and project nurse Lillie Mae McCormick; all the staff members but Ward were African Americans. A local physician, Thomas M. Adams, made periodic visits to the project. The residents grew cotton, pecans, peanuts, peaches, grains and corn, and vegetables, among other crops.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Another important feature of Flint River Farms was Flint River Farms, Incorporated, an 1,800-acre training farm designed to provide a hands-on education in agriculture to young married couples. Forty families lived in three residence centers and worked together at this large-scale farm, learning to maximize their labor and equipment in exchange for a salary.

School and Community

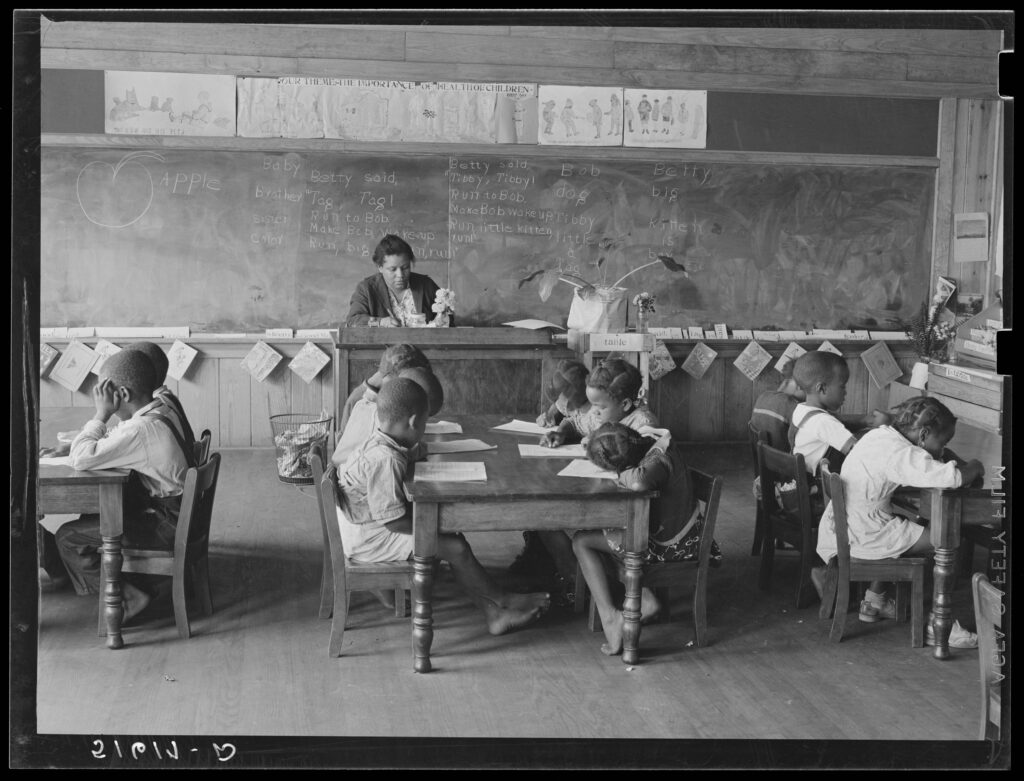

Educational training was provided to the project families through the Flint River Farms Community Center. The community center opened in 1938 and consisted of the six-room Flint River Farms School building, principal’s home, kitchen and dining room for the hot lunch program, auditorium, vocational agriculture shop, and health building.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The center opened its doors with 315 elementary students and 6 African American teachers: Odessa Engram, Florence Gray, Anne Greene, Minnie Head, Pauline Johnson, and Ellis Whitaker, who also served as principal. By 1946 all twelve grades were covered, and by 1955, 13 teachers were instructing more than 500 students with a curriculum that included courses in arithmetic, reading, social studies, science, library usage, industrial arts, music, physical education, geography, handwriting, grammar and usage, oral expression, history, English, and biology.

The Flint River Farms School also served as a training center for African American student teachers from Fort Valley State College (later Fort Valley State University). The young college students, living at homes near the school, completed their hands-on practical training and experienced the realities of farm life under the direct supervision of project teachers. The school gave special attention to vocational education as well, offering courses in farm management, livestock and poultry care, and home economics, with a focus on gardening, canning, and cooking. Evening classes were also held for adults. Cooperative extension agents from Fort Valley State College augmented the efforts of the project staff and school instructors.

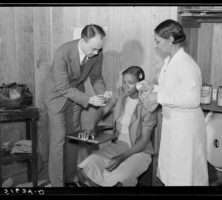

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In addition to their academic and vocational training, Flint River Farms School students also participated in extracurricular activities, including sports. In 1952 the Flint River Farms girls’ basketball team won the Georgia State “C” championship. The school also provided a number of “firsts” for the children in Macon County. It was the first to provide transportation for African American students, the first to provide regular health examinations with a school nurse and visiting physician, and the first to offer a high school education for many of the local residents.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

World War II and Beyond

The benefits derived from the Flint River Farms Resettlement Community were not restricted exclusively to land ownership. The project demonstrated successful community building for a group of people who had previously been limited to the lowest rungs of the social and economic ladder. It transcended mere economic relief by breaking through the social norms that were present during the Jim Crow era of segregation in Georgia, and it gained national attention as one of the more successful Black resettlement communities.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

At the same time, several factors worked against the progress made at Flint River Farms. First, conservative southern politicians resented the federal government’s efforts to intervene in local affairs. Second, World War II (1941-45) refocused the nation’s efforts, in both the financing and the direction and supervision of resettlement projects. And finally, during the war many participating farmers at Flint River Farms joined the armed forces or sought employment at the newly constructed Robins airfield (later Robins Air Force Base), located about fifty miles away, near Macon.

After the war, in 1946, a local physician, C. P. Savage, bought twenty-six of the Flint River Farms houses and moved them to Virginia Circle, a small neighborhood in Montezuma, to provide homes for returning white veterans. The community was dealt another serious blow when the Flint River Farms School, which had long offered community education, health care, and social activities, was closed in 1965, and its elementary students were sent to D. F. Douglass Elementary School in Montezuma.

During the summer of 2004 the Flint River Farms School Preservation Society was formed. With the help of local residents, churches, and businesses, the group works to preserve the history of the Flint River Farms Resettlement Community and pays tribute to those who acted as pioneers at the community’s founding. Twenty-five acres from the original school site, obtained in 2005 by a long-term lease from the local board of education, were transformed into a community park. That same year the Georgia Historical Society erected a historical marker at the site, where yearly events include Community Awareness Day, a classic car show, and a Christmas-tree lighting and caroling celebration.