John Stith Pemberton was the inventor of the Coca-Cola beverage.

In his day Pemberton was a most respected member of the state’s medical establishment, but his gift was for medical chemistry rather than regular medicine. He was a practical pharmacist and chemist of great skill, active all his life in medical reform, and a respected businessman. His most enduring accomplishments involve his laboratories, which are still in operation more than 125 years later as part of the Georgia Department of Agriculture. Converted into the state’s first testing labs and staffed with Pemberton’s hand-picked employees, these labs almost single-handedly eliminated the sale of fraudulent agricultural chemicals in the state and ensured successful prosecution of those who tried to sell them.

Early Life and Career

Born on January 8, 1831, in Knoxville, in Crawford County, Pemberton grew up and attended the local schools in Rome, where his family lived for almost thirty years. He studied medicine and pharmacy at the Reform Medical College of Georgia in Macon, and in 1850, at the age of nineteen, he was licensed to practice on Thomsonian or botanic principles (such practitioners relied heavily on herbal remedies and on purifying the body of toxins, and they were viewed with suspicion by the general public). He practiced medicine and surgery first in Rome and its environs and then in Columbus, where in 1855 he established a wholesale-retail drug business specializing in materia medica (substances used in the composition of medical remedies). Some time before the Civil War (1861-65), he acquired a graduate degree in pharmacy, but the exact date and place are unknown.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The analytical and manufacturing laboratories of J. S. Pemberton and Company of Columbus were unique in the South. “We are direct importers,” the company claimed, “manufacturing all the pharmaceutical and chemical preparations used in the arts and sciences.” Established in 1860 and outfitted with some $35,000 worth of the newest and most improved equipment—some of it designed and patented by the company—it was “a magnificent establishment,” an enthusiastic reporter from the Atlanta Constitution proclaimed in 1869 when the labs were moved to Atlanta, “one of the most splendid Chemical Laboratories that there is in the country.”

Courtesy of Historic Columbus Foundation

Pemberton served with distinction as a lieutenant colonel in the Third Georgia Cavalry Battalion during the Civil War and was almost killed in the fighting at Columbus in April 1865. In 1869 he became a principal partner in the firm of Pemberton, Wilson, Taylor and Company, which was based in Atlanta, where he moved in 1870. Two years later he became a trustee of the Atlanta Medical College (later Emory University School of Medicine) and established a business in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where his own brands of pharmaceuticals were manufactured on a large scale. He also served for six years (1881-87) on the first state examining board that licensed pharmacists in Georgia.

Pemberton was “the most noted physician Atlanta ever had,” according to the Atlanta newspapers, but he is best known for his expertise in the laboratory, where he perfected the formula for Coca-Cola.

The Origin of Coca-Cola

A few years before Coca-Cola began its spectacular rise to international acclaim, a drink known as Pemberton’s French Wine Coca was extremely popular in Atlanta. Its fame spread throughout the Southeast, and the demand for the tasty beverage was high.

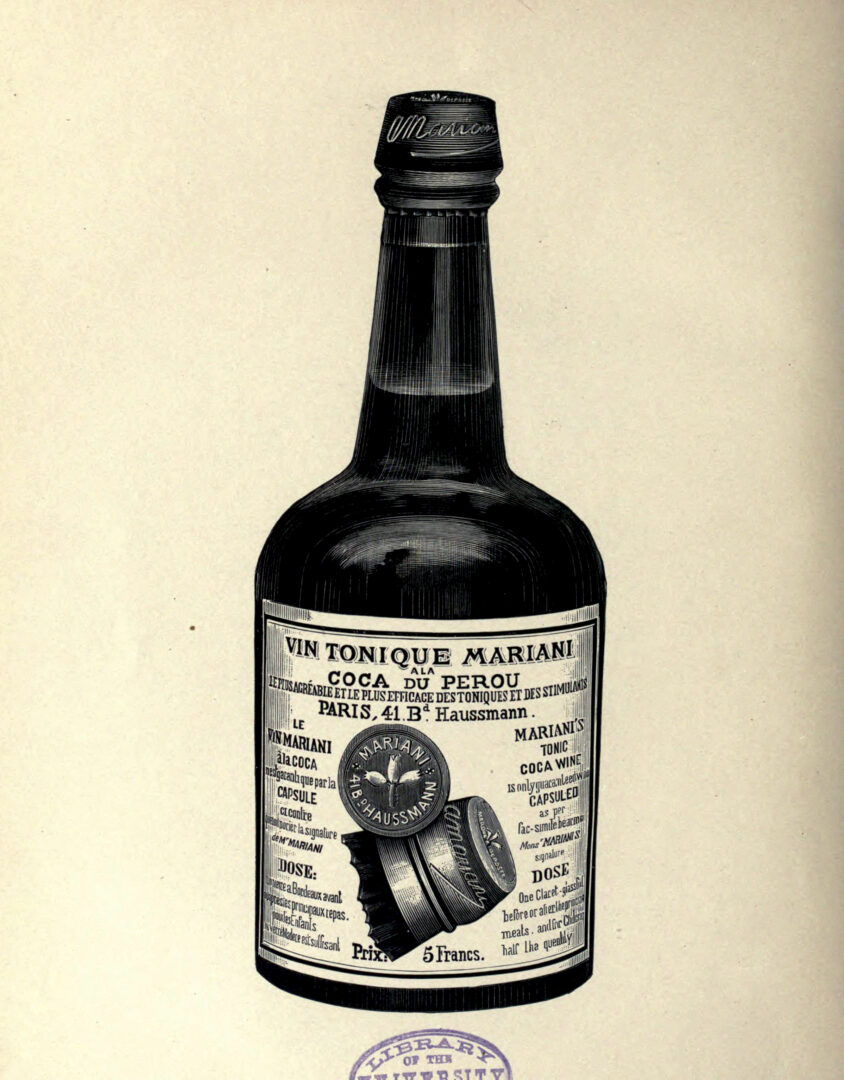

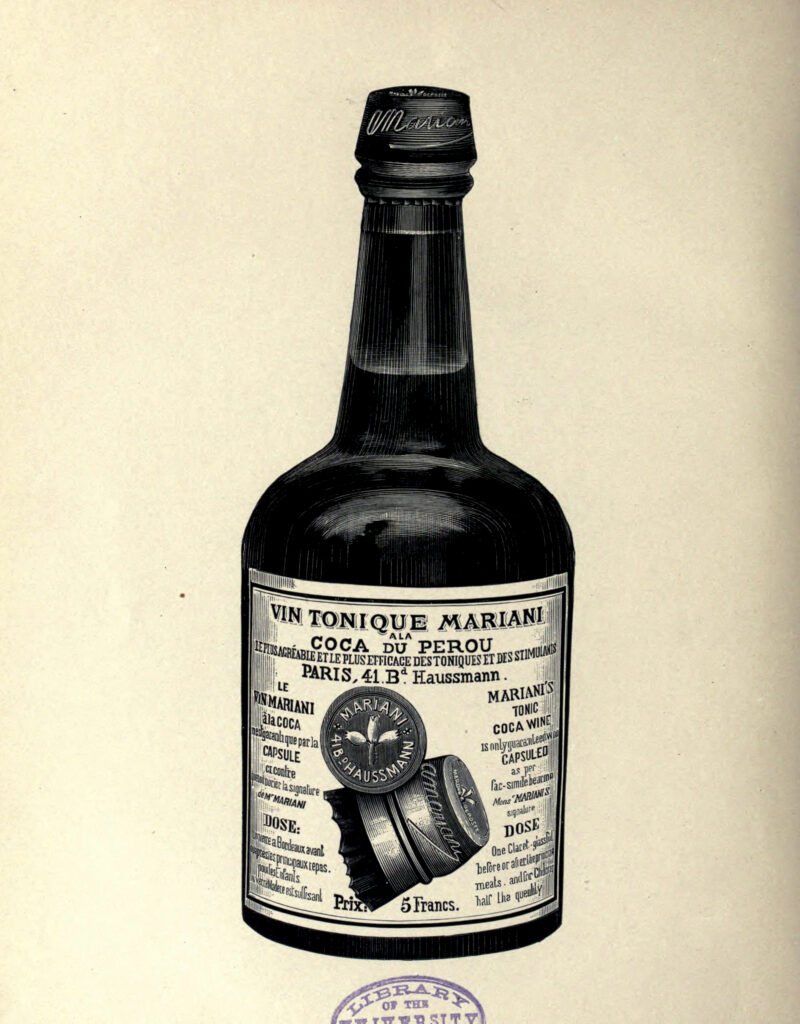

In 1885 a reporter from the Atlanta Journal approached the creator of French Wine Coca and asked him for a detailed analysis of the new drink. Pemberton replied, “It is composed of an extract from the leaf of Peruvian Coca, the purest wine, and the Kola nut. It is the most excellent of all tonics, assisting digestion, imparting energy to the organs of respiration, and strengthening the muscular and nervous systems.” He explained that South American Indians considered the coca plant a sacred herb and praised its beneficial effects on the mind and body. With the aid of the coca plant, the Indians had performed “astonishing” feats, he said, “without fatigue.” Pemberton then admitted that his coca and kola beverage was based on Vin Mariani, a French formula perfected by Mariani and Company of Paris, which since 1863 had been the world’s only standard preparation of erythroxylon coca.

Image from Wikimedia

In 1886 the city of Atlanta introduced prohibition, which, among other things, forbade the sale of wine. Pemberton decided to make another version of his popular drink. He dropped the reference to wine in the name of the beverage, substituted sugar syrup for the wine, and coined the name “Coca-Cola” to identify his formula. Henceforth, he would call Coca-Cola the ideal temperance drink, both on the label and in advertising.

Realizing that he needed financial backing to market this nonalcoholic version of French Wine Coca on a large scale, Pemberton formed a company for that purpose. He put his son Charles in charge of manufacturing Coca-Cola, and after prohibition ended in 1887, he again produced French Wine Coca. He announced that he would retire from active practice, sell his drugstores in Atlanta and elsewhere in the state, and devote all his time to promoting his beverages. Meanwhile, a group of businessmen responded to Pemberton’s appeal to finance the new Coca-Cola Company. He was to receive a royalty of five cents for each gallon of Coca-Cola sold.

It was Pemberton’s practice to organize a business as a copartnership and then convert it into a corporation. In March 1888, after being in business for eight months as a copartner, he filed the petition for incorporation of the first Coca-Cola Company in the Fulton County Superior Court. Five months later, on August 16, 1888, he died at his home in Atlanta.

On the day of Pemberton’s funeral, Atlanta druggists closed their stores and attended the services en masse as a tribute of respect. On that day, not one drop of Coca-Cola was dispensed in the entire city. At sunup the following day, a special train carried his body to Columbus, where a large group of friends, relatives, and admirers laid him to rest. The Atlanta newspapers called him “the oldest druggist of Atlanta and one of her best known citizens.”