Hancock County lies between the Oconee and Ogeechee rivers, in east central Georgia. It was founded December 17, 1793, and was named for John Hancock, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Sparta, established in 1795 and incorporated in 1805, is the county seat.

Hancock is steeped in history. Native Americans passed through the area via the Upper Trading Path, which extended from Augusta to connect with tribes all the way to the Mississippi River. The area attracted Revolutionary War (1775-83) veterans from Virginia, the Carolinas, and New England, who came to take advantage of the land lottery system. In 1825, on his American tour, the Marquis de Lafayette was hosted in Sparta by former Congressman William Terrell and others. By 1840 Hancock had given Georgia two governors, Nathaniel E. Harris and Charles McDonald, and had become well known for its strong educational institutions and religious affiliations.

In 1806 Georgia Methodists, as part of the South Carolina Conference of the Methodist Church, met in Sparta. Two prominent late-nineteenth-century Methodist bishops were Sparta residents: Bishop George Foster Pierce and his African American counterpart, Bishop Lucius Holsey. Presbyterians, Catholics, and Baptists also contributed to the early religious heritage of the county. Several male academies, at Powelton, Mount Zion, and Sparta, were nationally known; and the Sparta Female Model School attracted wealthy young girls from New England and the mid-Atlantic states. In 1862 Richard Malcolm Johnston’s famous boys’ school at Rockby set an example as a progressive institute of learning unique for nineteenth-century schools.

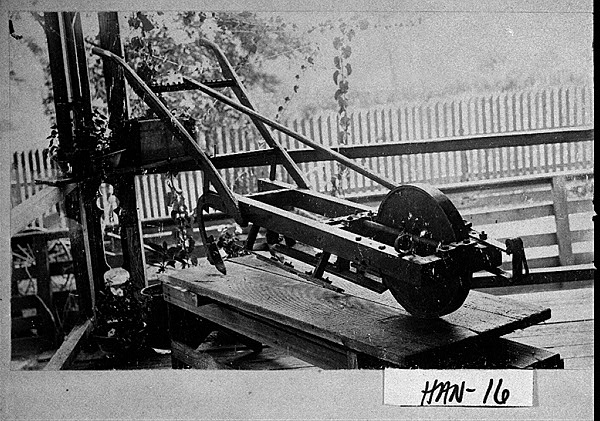

Cotton cultivated by thousands of enslaved workers brought prosperity to Hancock County by 1830. An 1835 census counted 5,680 enslaved persons and 480 slaveowners in the county. Advanced farming practices were introduced by innovative planters like David Dickson, who designed a plow and began the practice of using bat guano for fertilizer. Dickson, along with other progressive planters, founded the Hancock County Planters Club in 1837 to encourage improved agricultural achievements. It had a statewide influence on planters who witnessed the club’s enthusiasm and successful yields, and it helped turn the tide of emigration to western lands after cotton farming had depleted the soil.

In January 1861, when the Georgia Secession Convention convened, the three Hancock County representatives, all staunch Unionists, voted against withdrawal. When Georgia seceded, however, they threw their fortunes in with the Confederacy, and the county supported four years of war by supplying soldiers and turning cotton fields to corn and grain fields to sustain an army. Two Confederate generals were born in Hancock County, and Linton Stephens, the half brother of Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy, lived in Sparta from 1852 to 1872. The town of Linton (near Sparta) was named for him in 1858.

War came to Hancock County in November 1864, when elements of General William T. Sherman’s Union forces left Milledgeville on the infamous March to the Sea. Cavalry under Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick raided the southern part of Hancock along the Ogeechee River, destroying farms and burning cotton. But the real devastation came in the war’s aftermath. Most of the wealthy citizens left Sparta and Hancock County in the years following the war, and the area’s prosperity declined considerably during Reconstruction. William J. Northen, who had moved to the county in the 1850s and helped establish the Hancock County Farmer’s Club, was elected governor of Georgia in 1890.

Hancock never recovered its antebellum reputation as one of the richest counties in the state. The twentieth century saw a small return to farming, especially cotton, but by the 1940s that was gone, in large part due to the arrival of the boll weevil and timber replaced cotton as the county’s main source of revenue. In 1921 writer Jean Toomer arrived in Sparta to work as the substitute principal at a Black industrial school. Toomer’s experiences in the community inspired his acclaimed novel Cane, which was published in 1923.

Sparta and Hancock County gained notoriety in the late 1960s and early 1970s when Black activist John McCown exerted his influence there. As executive director of the Georgia Council on Human Relations, a statewide civil rights organization affiliated with the Southern Regional Council, McCown made Hancock County the focus of his efforts to change the political power structure. He succeeded in bringing millions of dollars in federal grant money to the county and transforming it into a Black-controlled county but his successes were tainted by questionable business practices and charges of mismanagement of several projects. While some saw him as a force for racial change in politics, others viewed him as an opportunist who rather than improving race relations instead set them back.

Hobbled by a legacy of political unrest and a weak economy, Hancock County’s population consistently declined during much of the twentieth century. Once one of the richest counties in the state and now one of the poorest, Hancock ranks at the bottom of the state’s counties in education and economic welfare. There have been efforts to capitalize on Hancock’s rich history, including plans for heritage tourism with a museum and historical tours. Several National Register historic districts and sites are located around the county and in Sparta. In 2003 several roads in Hancock County became part of the Historic Piedmont Scenic Byway, a route that is intended to promote the historical and cultural features of the county.

In 2014 the historic Hancock County courthouse, constructed from 1881-1883 was consumed by a fire that raged for three weeks. The flames reportedly became so hot that the 800-pound clock tower bell melted. An important civic center for residents, the courthouse was rebuild and recommissioned in 2016–an effort that resulted in $7.5 million in costs.

According to the 2020 U.S. census, the population of Hancock County is 8,735, a decrease from the 2010 population of 9,429. A 2021 census found the population of Hancock County was 73 percent Black or African American.