The longleaf pine and grassland forest of the southern Coastal Plain is among the most endangered ecosystems in North America.

Its native range once stretched from southern Virginia to east Texas, covering almost 90 million acres. In Georgia it ran roughly below the fall line in the Upper Coastal Plain, though longleaf sometimes flourished across the lower Piedmont as well. But by 2006, only 3 million acres of longleaf forest remained in the South, and of that, only about 12,000 scattered acres retained an old-growth component with a biologically diverse understory. One study estimated that Georgia’s acreage dwindled from more than 4 million acres of longleaf forest in 1936 to just 376,400 acres in 1997. Today, due in large part to the efforts of conservationists, scientists estimate there are approximately 4.5 million acres of longleaf across the region.

Longleaf Pine–Grassland Ecosystem

This longleaf pine–grassland system is what ecologists call a fire-climax community; the species in this ecosystem are not only resistant to fire but also dependent upon it. Historically the resinous longleaf needles, along with an understory that usually contained highly flammable wiregrass, carried lightning-set and anthropogenic ground fires throughout the entire range of the forest. Longleaf pines require bare mineral soil for their seeds to germinate, and they have adaptive strategies for surviving fires during the early stages of their development. After the seeds germinate, the longleaf establishes a long tap root below ground and spends three to fifteen years in a grass stage, with long needles that protect the terminal bud from fire. Without frequent fire, the understory grows up in a thick rough, allowing successional hardwoods or the less fire-resistant slash and loblolly pines to encroach upon the uplands. Eventually these other trees crowd out longleaf and other herbaceous groundcover, thus setting the landscape on a different developmental trajectory.

The longleaf pine is the dominant tree species in this system and is essential to its integrity, but the floral and faunal diversity of the system lies in its understory. In fact, the longleaf pine–grassland forest may well be the most diverse North American ecosystem north of the tropics, containing rare plants and animals not found anywhere else. The understory throughout the longleaf range contains from 150 to 300 species of groundcover plants per acre, more breeding birds than any other southeastern forest type, about 60 percent of the amphibian and reptile species found in the Southeast—many of which are endemic to the longleaf forest—and at least 122 endangered or threatened plant species. In Georgia, habitat loss and fragmentation have placed species like the red-cockaded woodpecker (Picoides borealis) on the federal endangered species list and made the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) a threatened species. Other imperiled markers of forest health are the flatwoods salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum), the eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon corais couperi), the striped newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus), and the Florida pine snake (Pituophis melanoleucus mugitus).

The longleaf-grassland forest that we know today is a natural system of Holocene origin. In other words, it has most likely never existed absent a human presence. Indeed, some researchers estimate that this ecosystem is no more than 5,000 years old. Native Americans arrived in the coastal-plain region while the system was taking shape, and there is considerable evidence that their land-use practices shaped the forests that Europeans found when they moved into the region thousands of years later. When those latter groups did arrive, between 1600 and the late 1800s, they coexisted tenuously with the longleaf-grassland ecosystem, altering it and substantially degrading it in places but never threatening its existence.

Economic History

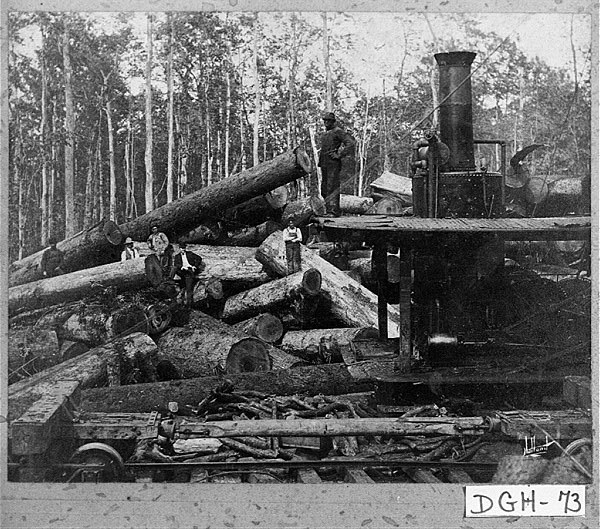

Historically longleaf pine was an important economic resource for Georgians, providing high-quality lumber for building materials; raw materials for the naval stores industry, from colonial settlement until well into the twentieth century; and forage for settlers’ cattle and hogs, which ranged freely throughout the forest to feed on the lush understory. Over time, several factors led to the forest’s decline. One of the most damaging came from the movement of the large-scale timber industry into the South from 1880 to 1920, as well as the subsequent exclusion of fire from the system by foresters who were well intended but deeply misinformed about longleaf-forest ecology. After a sustained fight throughout the twentieth century by such conservationists as Herbert L. Stoddard and Leon Neel, foresters now recognize fire as a valuable forest-management tool.

The difficulties that confront those interested in longleaf restoration are many. A long tradition of private land rights in the South makes it difficult to thwart commercial and residential development, and industrial forestry and agriculture continue to dominate much of the historical longleaf range. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, both industrial and nonindustrial forests converted longleaf lands to fast-growing, short-rotation slash and loblolly pine stands to feed Georgia’s growing pulp and paper industry. With the decline of pulp and paper in the last decade, there has been an effort to restore some of these lands to longleaf, but a lack of incentive and, most importantly, knowledge about longleaf ecology has proven a difficult gap to bridge. Even on lands where longleaf-grassland restoration is the primary goal, the fragmented nature of today’s southern coastal plain makes controlled fire increasingly difficult to use as a management tool.

Restoration and Conservation

In Georgia, in particular, there has been a strong effort toward restoration. Janisse Ray, in her elegant book of essays Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (2001), exposed many Georgians to the beauty and importance of the longleaf-grassland ecosystem. Several good examples of longleaf-grassland forest remain in the state. The military bases Fort Stewart and Fort Moore (formerly named Fort Benning) have the largest remaining blocks, while the Nature Conservancy controls several thousand acres, the Moody Tract in Appling County being its best holding of old-growth longleaf. In 2017, the state acquired the Sansavilla Wildlife Management Area, a nearly 17,000–acre stretch along the Altamaha River, with the aim of revitalizing its longleaf pine. Several high-quality stands also thrive on privately held lands, especially on some large quail plantations near Thomasville and Albany, including the Birdsong Nature Center and the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center at Ichauway. Groups like the Longleaf Alliance, the Georgia Forestry Commission, and the Georgia Forestry Association have encouraged private landowners to restore the coastal-plain environment to longleaf as well.